|

| [Click to Enlarge] |

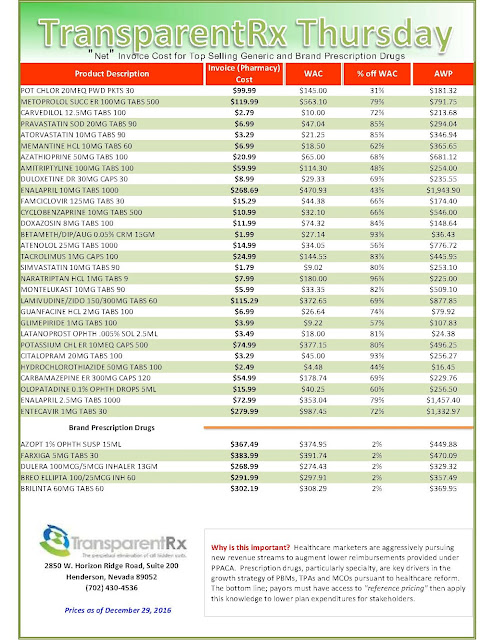

While Congress has taken drug executives to task with high-profile committee investigations of price increases on everything from HIV medication to EpiPens, a crucial link in the drug-price chain has gone largely unscathed: pharmacy benefit managers, who play an obscure by significant role in determining the cost paid for prescription drugs by tens of millions of Americans.

But as the new Republican Congress once again takes on the task of overhauling the U.S. health care system, the relative anonymity of PBMs might be about to come to an end.

As PBMs have grown in size, they have begun attracting an increasing amount of controversy over their how much savings they actually produce, which could make them a target for state legislatures and as part of any repeal of the 2010 health care law.

Criticism has mounted from pharmacists, consumer advocates and large employers, who claim that PBMs are abusing their position as middlemen in a complex industry to reap huge profits, while providing little in return to clients and consumers. PBMs, though hardly a household name, are nothing new in American health care.

The first ones were formed in the 1970s to serve as intermediaries between the health plans that covered pharmaceutical prescriptions and the pharmacies that filled them. Initially this role was administrative, with PBMs merely shuffling paper between the two groups.

As drug costs continued to rise however, PBMs were able to sell themselves not just as administrative functionaries, but as managerial experts who could use their knowledge of the pharmaceutical industry to deliver more effective, less expensive prescription benefit programs.

This reinvention of PBMs has led to an explosion in their size and scope.

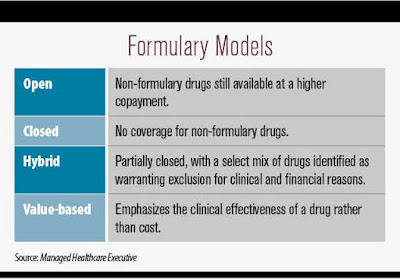

Today, PBM companies like Express Scripts and CVS Caremark handle everything from negotiating prices with drug manufacturers and setting co-pays, to creating pharmacy networks and determining which drugs your health plan will cover.

The added responsibilities PBMs have taken on has proven very lucrative for the industry, which pulls in roughly $423 billion in annual revenue.

Express Scripts alone — the largest PBM — earned $101 billion in revenue 2015, and is responsible for the drug coverage of more than 100 million people.

Beating the spread

The problem, says Susan Pilch, of the National Community Pharmacy Association, is the PBM industry’s lack of transparency.

Everything from negotiating with drug manufacturers, to reimbursing pharmacists is done in secret, says Pilch, which enables PBMs to charge outrageous prices to their clients, which more than make up for any discounts they might extract from drug manufacturers.

To illustrate this point, she provides the example of spread pricing, where a PBM will reimburse pharmacies for the cost of filling a prescription at one price, and then turn around and charge a higher price to their client for the same drug.

Tyrone’s comment: While I’m a critic of legacy PBMs and their lack of transparency, some of the blame for their opacity goes directly to purchasers of PBM services and the consultants they rely upon. The truth is a proclaimed benefits expert can’t simply request a claims analysis from one PBM then pass it around the country from one PBM to another looking for the best “deal.” This is what’s happening and leads to temporary price concessions only to see net plan costs rise YOY. The key to binding transparency and elimination of overpayments to pharmacy benefit managers is developing the ability to drive disclosure of details on services important to you.

“They basically make a spread for themselves,” Pilch says. “And the plan is not necessarily privy to all of these behind the scenes things. If you ask the plan, they would probably assume what the PBM is charging them is what they are paying the pharmacy.”

An example of this can be seen in the experience of Meridian Health Systems, a non-profit hospital system in New Jersey, which contracted with Express Scripts in 2008 to manage its employee prescription drug benefit program. As reported by Fortune Magazine, Meridian saw the cost of its drug benefit program increase by more than $1 million after contracting with Express, despite the company’s promise to save it money.

Unlike most companies however, who are aware only of what their PBM is charging them, Meridian was able to cross-reference what Express Scripts was billing them for filling prescriptions against what they were reimbursing Meridian’s own pharmacies for those same drugs. What Meridian found was that Express Scripts was collecting a spread on almost all the prescriptions, in some cases in excess of $60 per prescription.

And the Meridian case is hardly unique.

In March 2016, Anthem — of the nation’s largest insurers — brought a $15 billion lawsuit against Express Scripts for a similar pattern of alleged overcharging, which they claim has led to “massive damages to Anthem and an obscene profit windfall to ESI.” This charge is based on a third-party audit, which found Express Scripts was billing Anthem above competitive benchmark rates for drugs, to the tune of $3 billion per year.

Two further class action lawsuits have since been filed against both Express Scripts by members of Anthem health plans who claims these excessive prices have led to them paying far more in pharmaceutical co-pays and other expenses.

Express Scripts denied any wrongdoing and filed a countersuit against Anthem, saying it has adhered to the contractual obligations it has made to the health insurance company.

As drug costs continued to rise however, PBMs were able to sell themselves not just as administrative functionaries, but as managerial experts who could use their knowledge of the pharmaceutical industry to deliver more effective, less expensive prescription benefit programs.

This reinvention of PBMs has led to an explosion in their size and scope.

Today, PBM companies like Express Scripts and CVS Caremark handle everything from negotiating prices with drug manufacturers and setting co-pays, to creating pharmacy networks and determining which drugs your health plan will cover.

The added responsibilities PBMs have taken on has proven very lucrative for the industry, which pulls in roughly $423 billion in annual revenue.

Express Scripts alone — the largest PBM — earned $101 billion in revenue 2015, and is responsible for the drug coverage of more than 100 million people.

‘Sophisticated health purchasers’

PBMs claim that their growing stature and importance is a product of their proven ability to drive down the cost of pharmaceuticals for their clients, which they purport to do in three ways.

— The first is through pooling of their clients’ buying power to extract large upfront discounts off the list price of a drug from the manufacturers, usually running between 15 to 21 percent for brand name drugs, which are then passed on to the client.

— The second is through the designing of drug plans to make greater use of cheaper generic medications, and more efficient mail-order pharmacies.

— The third is the ability of PBMs to obtain huge rebates from drug manufacturers in exchange for agreeing to cover particular drugs, and attach to them lower priced co-pays.

But the opaqueness with which PBMs operate has raised concerns not just about the prices they charge, but also what proportion of manufacturer rebates they pass on to their clients.

Read more: http://watchdog.org/285187/pharmacy-benefit-managers-legislative-crosshairs/