Multi-source prescription drugs are those which are manufactured by multiple companies; upon expiration of a marketing exclusivity period. FDA approval of these companies is required, obviously. These approved companies generally manufacture only generic pharmaceuticals. Some examples include Dr. Reddy’s, Watson, Actavis, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and others.

Since there are multiple companies competing against one another, prices are much lower for multi-source prescription drugs compared to single source prescription drugs. This is not the case for single source prescription drugs.

Single source prescription drugs are those for which there is only one manufacturer. In other words, there is not a generic medication available in the market thus the brand drug is the only option for physicians, patients and payors. One exception to the single source methodology does exist.

An 180-day marketing exclusivity is offered by the Food and Drug Administration to the first company which successfully submits an application to manufacture a replica (a copy of the exact chemical ingredients] of a brand prescription drug after the initial patent has expired. For all intent and purposes, the medication manufactured by a company granted a 180-day marketing exclusivity is considered single source.

The application process for the 180-day marketing exclusivity is very complicated. If you like, read more about it here: 180-Day Generic Drug Exclusivity Under the Hatch-Waxman Amendments to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. Prescription drug patents, for innovator drugs, typically expire after 17 years.

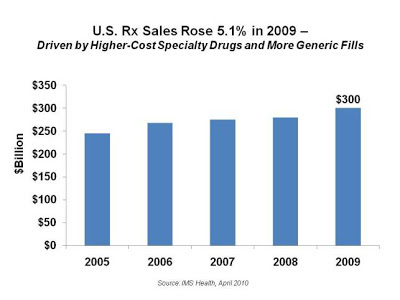

Generic Dispensing Rates continue to rise yet it defies logic that prescription drug sales revenue also continues to increase year after year. This begs the question, “why do prescription drug sales continue to increase?” The state of personal health and healthcare in our country notwithstanding there are two primary reasons: brand and specialty pharmaceuticals.

Let me explain. Drug manufacturers have an obligation first to their stakeholders and rightfully so. They’re keenly aware of the stiff competition from generic equivalents and the government’s (largest payor) desire to lower overall costs. In turn, they find ways to plug revenue gaps.

To protect brand product revenue streams manufacturers go to great lengths. They will fight to extend the patent expiration date, seek additional indications (often marketed under a different name), and even partner with competitors.

If you had a monopoly on a prescription drug or an entire disease state for 17 years what would you do to protect it? More importantly, how much would you charge for the right to use the medication? Keep in mind you’re operating as a for profit business. It’s not uncommon for a brand drug manufacturer to generate EBITDA margins of 70% or greater.

Almost every original manufacturer now has at least one specialty and/or biotech drug in its portfolio. It’s part of an overall strategy to help patients. Coincidentally specialty drugs are more difficult, from a financial and scientific standpoint, to duplicate. Nonetheless, biosimilars will play an increasingly important role in the near future.

Employers and other payors have a role, albeit small, in how the drug spend trend will play out. Here is one thing all individuals and organizations can do to slow the trend: don’t pay for any brand prescription drug when there is a generic equivalent in the pharmacies unless it is the last option.