How pharmacy benefit managers (PBM) make money is an extremely complex web of deception. Non-fiduciary pharmacy benefit managers say, “We will contain your costs. We will lower drug prices.” They have not backed up their words with action. Instead, non-fiduciary pharmacy benefit managers have opted for personal financial gain at the expense of clients, plan participants and other stakeholders. Some pharmacy benefit managers have even gone as far as to admit publicly that it isn’t their responsibility to contain prescription drug costs. PBMs have three primary responsibilities: cost-containment, safety, and healthcare outcomes. The pharmacy benefits management industry, including consultants, has done a poor job in all three areas. Let’s look at five ways how non-fiduciary PBMs make money by skirting cost-containment responsibilities.

Formulary Steering. Occurs when patients are steered toward certain brand drugs on formulary when a lower cost usually generic equivalent or therapeutic alternative is available. A newly unsealed whistleblower suit claims that multiple CVS Health subsidiaries coordinated to prevent members from accessing generic drugs in a bid to boost the bottom line. The suit was filed by Alexandra Miller who worked at CVS for nearly two decades before leaving the company three years ago. Miller claims that CVS’ SilverScripts Part D subsidiary as well as its Caremark pharmacy benefit manager and retail pharmacies worked together to prevent access to generics, which allowed it to pocket higher rebates because members were pushed to buy branded medications rather than lower-cost options. Miller says that when she reported the behavior to a superior, she was told that the company had decided the benefits of the alleged scheme outweighed the likelihood of being caught[i].

Rubberstamping. Happens when a pharmacy benefit manager doesn’t employ utilization management protocols effectively. Drug utilization management includes but is not limited to prior authorization, step therapy, quantity limits, refill to soon, and drug utilization reviews. The New York City Transit Authority hired ESI to administer and manage the prescription drug benefits NYCTA offered to its employees, retirees, and dependents. In the year prior to contracting with ESI, NYCTA paid $6 million for compounded prescription claims. To the shock and awe of the NYCTA, in the first year of its contract with ESI, NYCTA paid over $38 million for compounds. In fact, in June 2016, only two months after the contract term began, an individual’s claim for an erectile dysfunction compound medication totaled $405,325.43 over three months. Critically, a sizable portion of the compound claims contributing to the substantial increase in spending originated from just three providers and were largely fraudulent. Disturbingly, ESI conducted its own investigations into two of the providers and neglected to share the results with NYCTA. ESI likely approved overpriced compounds because ESI may have earned “spread pricing” on such claims—this litigation will reveal the truth[ii].

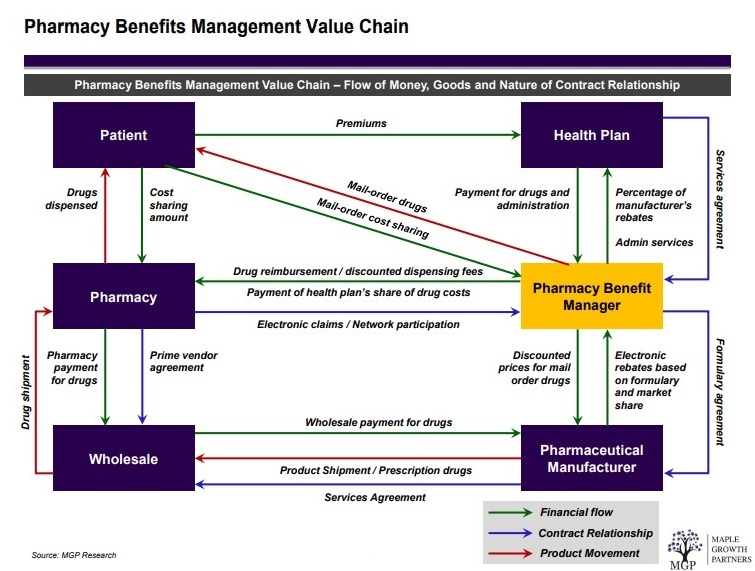

Spread Pricing. Takes place when a pharmacy benefit manager reimburses a network or in-house pharmacy less than the amount billed and subsequently collected from a plan sponsor (see figure 1). The state of Ohio released data showing how private companies manage $2.5 billion in public money for pharmacy benefits for Ohioans on Medicaid. The middlemen, called pharmacy benefits managers, are under scrutiny for how transparent they are in how the public money gets spent. The report shows the companies retained (spread) $223.7 million of the money they billed Medicaid. The state of Ohio promptly terminated each contract.

Rebates. Have increased in lock step with list price since at least 2013. For example, internal company documents collected for the U.S. Senate Committee’s investigation show that, in 2013, average rebates for long-acting insulin products hovered around 2% and 4% for preferred formulary placement. However, approximately six years later, rebates for the same product were as high as 79.75%[iii]. It’s important to note that rebates vary by product, payer, and placement on a plan’s formulary. WAC data collected for the Committee’s investigation also suggest list prices for long-acting and short-acting insulins have increased rapidly during this same period.

Information Asymmetry. Is an imbalance between two negotiating parties in their knowledge of relevant factors and details. Typically, that imbalance means that the side with more information enjoys a competitive advantage over the other party. Non-fiduciary PBMs and some advisors have been leveraging information asymmetry or information failure to their financial benefit. Documents provided to Axios[iv] reveal a new layer of secrecy within the maze of American drug pricing — one in which firms that manage drug coverage for hundreds of employers, representing millions of workers, obscure the details of their work and make it difficult to figure out whether they’re providing a good deal. Each of the predominant health care consulting firms — Aon, Mercer, and Willis Towers Watson — has its own prescription drug coalition made up of employers. The conventional wisdom is firms use the combined scale to negotiate lower drug prices with large pharmacy benefit managers, but there’s no hard evidence the coalitions provide meaningful savings.

Conclusion: How pharmacy benefit managers (PBM) make money

John F. Kennedy said, “The greater our knowledge increases the more our ignorance unfolds.” Most self-insured employers, and their advisors, don’t know what they don’t know. Pharmacy Benefit Managers provide transparency and disclosure to a level demanded by the competitive market and generally rely on the demands of prospective clients for disclosure in negotiating their contracts. The best proponent of transparency is informed and sophisticated purchasers of PBM services. The purchaser needs to understand not only what they want to achieve in their relationship with their PBM but also the competitive market and their ability to drive disclosure of details on services important to them. Assessing transparency is done more effectively by a trained eye with personal knowledge of the purchaser’s benefit and disclosure goals. Consequently, the average self-insured employer is paying 67% more for PBM services than needed.

[i] Paige Minemyer, Senior Editor, Whistleblower suit: CVS prevented Part D members from accessing generics, June 16, 2022, Fierce Healthcare, https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/payers/whistleblower-suit-cvs-prevented-part-d-members-accessing-generics.

[ii] Jonathan E. Levitt, Esq., Dae Y. Lee, Pharm.D., Esq., CPBS, and Adam C. Farkas, Esq., PBMs could be driving up plan sponsors’ drug costs, June 15, 2022, BenefitsPro, https://www.benefitspro.com/2022/06/15/pbms-could-be-driving-up-plan-sponsors-drug-costs/.

[iii] Congress of the United States, 5/16/2022, FTC-2022-0015-0001 Solicitation for Public Comments on the Business Practices of Pharmacy Benefit Managers and their Impact on Independent Pharmacies and Consumers.

[iv] Bob Herman, 12/6/2021, Documents reveal the secrecy of America’s drug pricing matrix, 12/21/2021, <https://www.axios.com/2021/12/06/aon-express-scripts-contract-employers-drug-price-data>