The 10-page “book” sponsored by TrialCard, a vendor of co-pay cards and vouchers, promises insights into “Patient access needs and hurdles along the specialty drug pathway, supplemented by trends, data and insights on this shifting market.” It’s not just an interesting read for snoopy reporters but it’s a cautionary tale for journos and the public about future health system costs and how patients are manipulated in the quest for even greater profits.

The tip-off for what this itty-bitty volume can do for a drug maker comes in this statement:

“Clearly there is a vast undermet need for greater access to specialty medications and better support services for patients. The answer, for pharma, surely lies in an integrated, coordinated patient-centric approach.”

In other words, pharma can and should, the book advises, hold patients’ hands from the time of diagnosis through the process of buying and paying for one of these uber-expensive medicines, and make sure the patient stays on the drug regimen. That’s the name of the game in the drug biz. Long-term use equals more drugs sold equals more profits.

Clever drug companies have amassed an arsenal of strategies for getting more drugs into the hands of patients through speaking fees to doctors who prescribe the drugs, sponsorship of medical education programs, and very effective detailing or selling in the doc’s office to push the latest and greatest.

This time, though, the strategy is aimed at the patient’s pocket book, and the new world of specialty drugs opens up a box of possibilities for expanding their co-pay programs in which the drug company pays a significant portion of the cost-sharing an insurer requires. Pollpeter told me, “when a co-pay is optimized for the patients, they stay on the drug longer.”

How do these programs work?

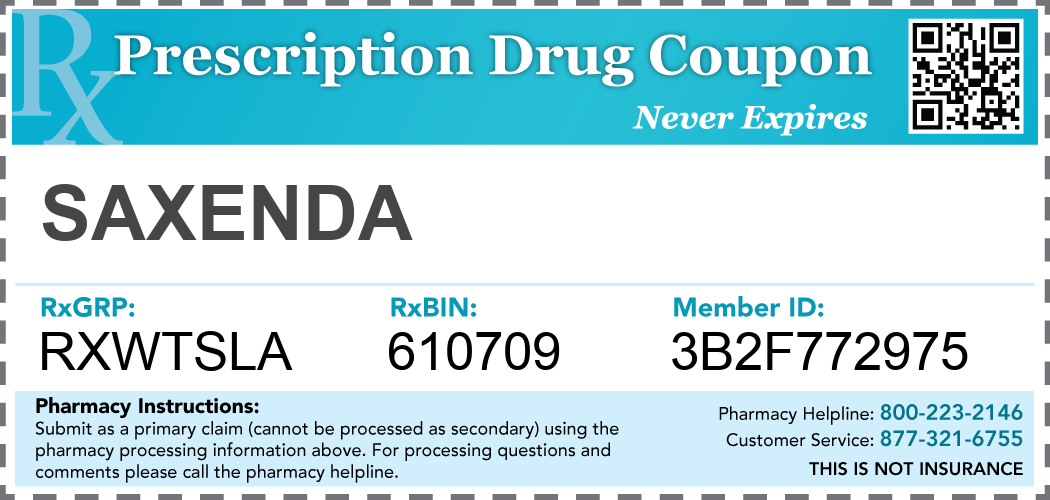

|

| Manufacturer Drug Coupon Example |

There’s the basic coupon, which doctors and druggists sometimes hand out, or patients can find them online. The industry calls them “pay-no-more” cards, telling patients they will pay no more than, say, $50 for their prescription. Discounts vary by therapeutic class with some drugs carrying larger discounts than others. Some work like loyalty programs. A patient can get a certain number of drugs for free after they’ve bought so many. That’s sort of like accumulating points for a free massage at a nail salon.

Then there are e-vouchers in which a prescription is sent from the pharmacist through a switch vendor that may provide other financial support to the patient. The drug maker works with the vendor to establish how much of the required cost sharing it will pay as well as other rules for the transaction. Both the rules and amounts the drug maker pays vary by the class of drugs. “The patient is blinded to the e-voucher,” Pollpeter says. “But they are happier when they see a lower copay.”

What’s wrong with this?

It seems like a win-win for the patient and the drug company, right? The patient pays less out of pocket—sometimes a lot less. In one example, the e-book notes that a patient’s out-of-pocket spending for specialty drugs for MS and rheumatoid arthritis can be as little as $5 a script. The manufacturer reaps more sales because patients are less likely to abandon therapy. But there’s one significant downside. High drug prices are still with us. “Coupons shield consumers from the true cost of medications and are less likely to make decisions based on the true cost of the drug,” says Troy Filipek, an actuary with the consulting firm Milliman.

“There’s nothing transparent about any of this,” says John Rother, the CEO of the National Coalition on Health Care whose project the Campaign for Sustainable Rx Pricing has helped raise public awareness of the skyrocketing cost of medicines. “Effectively these programs raise overall costs in the name of protecting patients, but for everyone else they raise costs and therefore premiums. It obscures the fundamental issue of unsustainable pricing for many pharmaceuticals.”

By Trudy Lieberman