|

| [Click to Enlarge] |

Combined, those factors are creating a perfect storm that virtually mandates a key role for hospital inpatient pharmacy in a health system’s or hospital’s clinical and financial decision making. Pharmacy, until recently (or in some cases, still) relegated to simply dispensing drugs from the basement, needs to find its way upstairs, unleashing its ability to manage chronic disease, reduce readmissions through rigorous medication reconciliation while a patient is in the hospital and be a team member that helps keep patients from returning to the hospital.

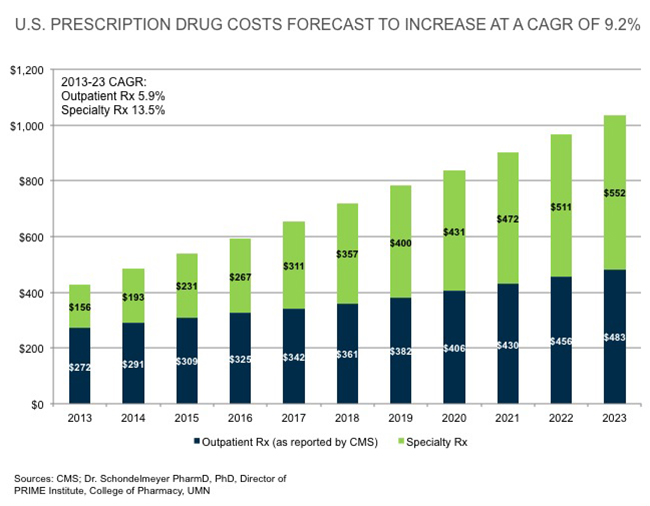

It does appear that the biggest driver to achieving that larger role is drug cost inflation, which even made its way onto the ECRI Institute’s 2016 Top 10 Hospital C-suite Watch List, usually a ranking of technology issues facing healthcare executives.

“The only person who can really get a handle on drug costs is the pharmacist,” says Marvin Finnefrock, PharmD, vice president of Clinical and Purchasing Services for Comprehensive Pharmacy Services (CPS), a national provider of inpatient and outpatient pharmacy management services to nearly 600 hospitals. “In many cases, we actually see a better patient outcome by not using the more expensive drug. We’ve known that for a long time, but now it seems like everyone is more aware of it.”

Taking advantage of the opportunity that knowledge creates hinges on a provider’s willingness to invest in some form of data analytics and, just as importantly, act on those findings. A widespread absence of information technology systems that support and track interventions adds to the challenges care providers face. Buying or creating these systems is expensive and comes at a time when capital spending is severely stressed by lower reimbursements and competing demands.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has been road-testing an initiative that includes a single payment for inpatient stay for joint replacement surgery, plus the post-acute care and all related services for up to 90 additional days. On April 1, CMS is making involvement in the test mandatory for 789 hospitals in 67 geographic areas across the country.

Meanwhile, as just one of many examples of private-payer bundled payment initiatives, on Jan. 1 the Pacific Business Group on Health Employers Centers of Excellence Network began contracting with hospitals for a single payment for bariatric surgery for employees of large national employers.

“Bundled payment and other programs are going to change how we have to manage drugs across a health system,” says Edward Choy, PharmD, president of Health Systems Operations for CPS. “Inpatient drugs used to be under formulary, while outpatient drugs were managed by private insurers and pharmacy benefit managers. Now, all drugs need to be managed under formulary. Finding the most cost-effective way to treat the patient becomes more of a priority.”

Choy and Finnefrock suggest a few key steps toward developing a long-term plan for the pharmacy piece of bundled payments. They include:

- Maintaining a relentless focus on outcomes. “Being ruthless when it comes to deciding on using a lower-cost drug or device that may go against established physician practice is essential,” Finnefrock says. “‘That’s the way we have always done it’ isn’t going to cut it anymore. It may make physicians feel comfortable, but it’s no longer a strategy for success or even, in some cases, survival.”

- Focusing on physician prescribing patterns and how they correlate with outcomes. “Presenting physicians with really robust outcomes data is a powerful tool for changing behavior,” Choy says.

- Taking a second look at generic drugs, even older drugs that may have lost cachet but not effectiveness. For example, new research favors the use of heparin, an older blood thinner that costs about $3 a dose, prior to percutaneous coronary intervention over the anticoagulant bivalirudin, which costs hundreds of dollars per case.

- Making pharmacy an equal partner in post-discharge care. “CPS research, about to be published, finds a 20 percent to a 50 percent reduction in readmissions from having a pharmacist make follow-up calls to make sure patients have filled prescriptions and understand how to take medicines,” Finnefrock says. That research updates a 2001 study in the American Journal of Medicine that found a pharmacist follow-up call reduced 30-day readmissions by more than half versus no intervention, while also improving patient satisfaction.

“It is pretty clear bundled payments are only going to get bigger as healthcare continues to try to get hold of rising costs,” Finnefrock says. “More and more providers are starting to understand that pharmacy can be a crucial ally in succeeding under these new value-based purchasing models.”

By Todd Sloane