|

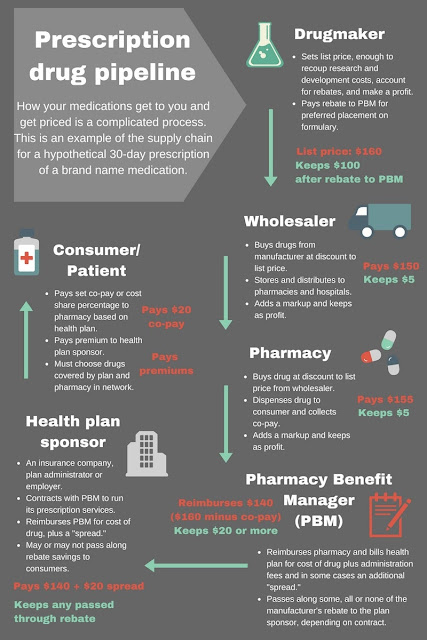

| Source: Blue Cross Blue Shield |

The National Business Group on Health (NBGH), a nonprofit association of 420 large U.S. employers, on Monday 1/30/2017 released a policy issue brief offering recommendations designed to help stem the skyrocketing costs of “specialty” drugs. Here are the NBGH’s recommendations:

1) Remove uncertainties surrounding risk-based and value-oriented contracting, and implement indication-specific pricing and reference pricing in public programs.

That’s a lot of health-care jargon. What does it mean? The fee-for-service model, in which a set price is paid for a drug irrespective of health outcomes, is antiquated and inefficient, the NBGH asserts. In response, industry stakeholders are experimenting with innovative, value-oriented solutions, often thought of under an umbrella concept commonly referred to as value-based payment (VBP) arrangements.

VBPs implicitly tie reimbursement amounts for health-care providers to patient outcomes or quality-of-life improvements.

One type of VBP arrangement is a risk-sharing agreement under which drug manufacturers agree to reimburse or discount their products when they do not work as intended. However, the NBGH asserts, current public policies inhibit the willingness of drug makers to enter into risk-sharing agreements — largely out of fear of their impact on laws such as the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, which established the “best price” provisions of the Medicaid drug-rebate program.

The law requires brand-name drug makers to provide the Medicaid program with the lowest price they charge for any drug to any other payer.

“The anticompetitive nature of the Medicaid best price program has been well documented by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, the Congressional Budget Office, and academic economists,” the NBGH report states. It adds, “We believe it is critically important to remove barriers to VBP arrangements, particularly those constraining the creation of risk-based contracting.”

As for the second half of the NBGH’s first recommendation, indication-specific pricing — an indication is a valid reason to use a certain medication, test, procedure, or surgery — also helps align payment for a drug to the value it delvers to a patient population.

The NBGH recommends that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) maintain an open dialogue with employers and other payers, as well as with manufacturers and providers, to identify opportunities for legislative changes to federal reimbursement policies that obstruct indication-specific pricing agreements.

And “reference pricing” is a form of defined contribution health benefits. Plan sponsors pay a fixed amount or limit their contributions toward the cost of a specific health-care service, and health-plan members pay the difference in price if they use a more costly health-care provider or service.

Some employers have successfully implemented such a policy for the use of specialty medicines where there is documented price variation based on where the treatment is administered.

The NBGH recommends that reference-pricing policies supported by clinical evidence be implemented consistently across public health-care programs.

2) Limit the reach of Medicare Part D protected classes.

Part D subsidizes the costs of prescription drugs and drug insurance premiums for Medicare beneficiaries. No physical exams are required, and applicants cannot be denied drug coverage for any reason.

While companies widely use the design of formularies — lists of medicines covered under insurance — to control drug costs, Medicare limits the freedom of Part D plans to control their formularies through specific rules. Two such rules substantially impact the price of drugs.

For one, federal regulations require that plan formularies include drug classes covering all disease states, with a minimum of two chemically distinct drugs in each drug class. That allows drug makers to manipulate pricing based on artificial market share, according to the NBGH.

Also, plans are required to cover all drugs in six protected classes: immunosuppressants, antidepressants, antipsychotics,

anticonvulsants, antiretrovirals and antineoplastics. What’s more, CMS has gone beyond the statute, requiring at least one drug in each subclass as well.

These rules limit the negotiating power of Part D plans and make drugs in those classes more expensive, the NBGH says.

The group recommends that Congress and CMS remove drugs from the protected classes where a sufficient generic exists. Also, it says, policymakers should work with employers and other stakeholders to gain consensus for Medicare drug-policy changes that would remove hindrances to effective negotiation of drug pricing by private payers.

3) Eliminate perverse payment incentives to providers under Medicare Part B.

Many specialty drugs are reimbursed through Part B, as such drugs often must be administered in a physician’s office or hospital outpatient department. For that reason, Part B providers typically buy the products in advance and bill Medicare for reimbursement after administration to the patient.

This reimbursement model creates a three-part, cyclical incentive for prices to continuously rise.

First, it encourages manufacturers to set prices higher and to incentivize providers to select those drugs—and receive a higher reimbursement. Second, it also creates an incentive for providers to continuously select higher-priced drugs, even when lower-cost alternatives might be available. And third, it incentivizes the delivery of these medications in higher-priced settings, such as hospital outpatient departments.

The NBGH recommends that such incentives be eliminated and that providers and manufacturers be encouraged to assume financial risk with regard to high-priced drug utilization.

4) Encourage the uptake of biosimilars.

A biologic drug is manufactured using a living system such as a microorganism of plant or animal cells. Historically, makers of such products were required to seek FDA approval as if they were an entirely new entity, submitting a full complement of product-specific data.

This did little to encourage market competition among the highest-price class of medications, even for similar products to treat the same disease.

The Affordable Care Act sought to alter the landscape of biologics, establishing an abbreviated approval pathway for those that can be demonstrated to be “biosimilar” to or interchangeable with currently approved biological products.

A 2014 Rand Corporation study suggested that robust uptake of biosimilar products could reduce direct spending on biologics by nearly $45 billion by 2024 by creating competition in a market that has traditionally been anticompetitive.

But the ACA has not led to a flood of biosimilar approvals. In fact, the FDA has approved only four of them since the law’s 2010 passage. By contrast, 20 of them have been approved in the European market. Safety, pricing, manufacturing, market entry, and physician and patient acceptance are all seen as tactical hurdles for stimulating competition in the biologics market.

The NBGH recommends that policymakers work with stakeholders to educate patients and providers on the safety and efficacy of biosimilar drugs.

5) Reform permissive patent and exclusivity protocols.

After the FDA approves a generic or biosimilar drug, it may take years for the cheaper versions to come to market. That’s largely because of litigation brought by the manufacturer of the original, brand-name drug. Such claims are based on legal questions about whether the patents for these drugs can be extended through various secondary approvals.

Deciphering and understanding the patent and exclusivity terms of pharmaceutical products is complicated because the two are intertwined and work in complementary yet distinct ways. And as these product-protection terms have become increasingly important to market share and profitability, the pharmaceutical industry fiercely protects them.

Drug makers’ ability to sustain high prices hinges on the monopolistic character of the pharmaceutical market, driven by these patent and exclusivity protections, which insulate products from competition and artificially boost the industry’s negotiating power, the NBGH says.

The group recommends that the market exclusivity period for biologics be reduced from 12 years to 7 years, and that patent extensions and exclusivity periods be limited or eliminated when they serve only to expand monopoly power.

Read more >>

See you Tuesday March 14 at 2 PM ET!

See you Tuesday March 14 at 2 PM ET!