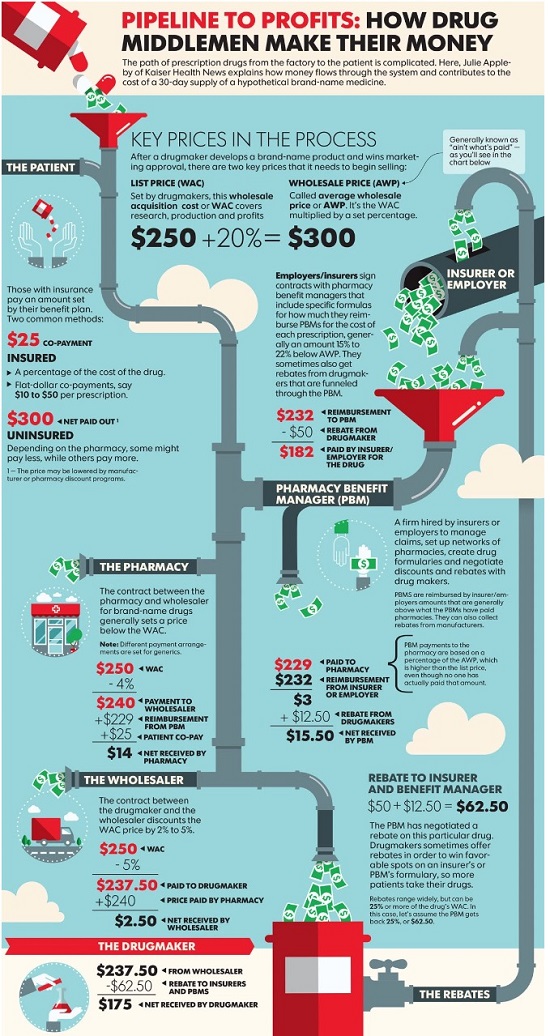

“Gross” Invoice Cost for Top Selling Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs – Volume 139

The costs shared below are what the pharmacy actually pays; not AWP, MAC or WAC. The bottom line; payers must have access to “reference pricing.” Apply this knowledge to hold PBMs accountable and lower plan expenditures for stakeholders.

Step #1: Obtain a price list for generic prescription drugs from your broker, TPA, ASO or PBM every month.

Step #2: In addition, request an electronic copy of all your prescription transactions (claims) for the billing cycle which coincides with the date of your price list.

Step #3: Compare approximately 10 to 20 prescription claims against the price list to confirm contract agreement. It’s impractical to verify all claims, but 10 is a sample size large enough to extract some good assumptions.

Step #4: Now take it one step further. Check what your organization has paid, for prescription drugs, against our pharmacy cost then determine if a problem exists. When there is a 5% or more price differential (paid versus actual cost) we consider this a problem.

Multiple price differential discoveries means that your organization or client is likely overpaying. REPEAT these steps once per month.

— Tip —

Always include a semi-annual market check in your PBM contract language. Market checks provide each payer the ability, during the contract, to determine if better pricing is available in the marketplace compared to what the client is currently receiving.

When better pricing is discovered the contract language should stipulate the client be indemnified. Do not allow the PBM to limit the market check language to a similar size client, benefit design and/or drug utilization. In this case, the market check language is effectually meaningless.

Note: Prices listed herein are gross thus do not account for rebates, discounts or other purchase incentives which ultimately reduces the net cost.

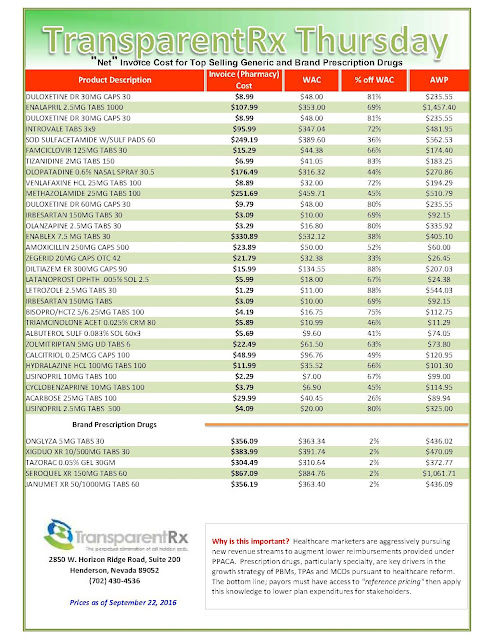

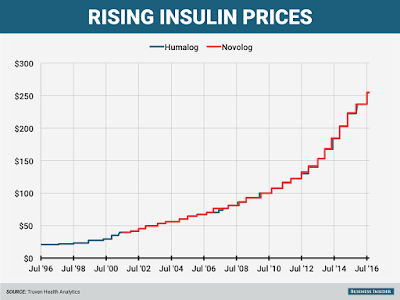

Insulin costs are way up, but drugmakers say PBMs are collecting the loot

|

| [Click to Enlarge] |

Targeted by critics complaining of big increases in the cost of insulin, pharma’s pointing the finger at pharmacy benefits managers, which are demanding larger rebates in return for access to their covered patients. It’s those demands that are pushing drugmakers to raise their list prices, Enrique Conterno, president of Eli Lilly’s diabetes business, told The Wall Street Journal.

Take Lilly’s long-successful insulin Humalog, for one. Its list price currently sits at $254.80 per vial, more than double its list price in 2011. But with rebates and discounts factored in, Lilly nets less in Humalog sales now than it did in 2009, Conterno said.

The Indianapolis drugmaker’s competitors–Lantus-maker Sanofi and Novo Nordisk–are feeling the pain, too. Both have already warned investors that falling net prices in the U.S. would hurt profits going forward; the average U.S. net price for Lantus is set to fall 10% this year after tanking by 17% last year, the WSJ notes, citing Bernstein estimates. And that’s after a list-price jump to $248.51 per vial from $114.15 in 2011.

The bigger problem? Thanks to a fragmented health insurance system, uninsured patients and those with certain healthcare plans are bearing part, if not all, of the increases themselves.

“There are more patients under high-deductible health plans and who may have a greater copay and coinsurance, and they’re being exposed to a larger share of the prices as well,” Harvard Medical School professor Aaron Kesselheim told the newspaper.

As the diabetes space continues to heat up, many industry watchers expect to see PBM formulary management tactics continue. They’ve already taken a serious toll on drugmakers in other spaces, too–such as hepatitis C and respiratory, where high prices and a wealth of competition have made payers aggressive about negotiating discounts.

But as vocal pharma pricing critic Steve Miller, CMO at leading PBM Express Scripts, told the Journal, his company is all for keeping net prices low despite the discount. “We never tell pharmaceutical companies we want high sticker prices. We want a low net price,” he said.

Tyrone’s comment: Every PBM wants a low net price. The difference though between traditional (any non-fiduciary PBM) and fiduciary PBMs is the extent from which payers benefit from the low “net” price acquired by their PBM. In a fiduciary arrangement, it’s 100% benefit and in all others it’s a crapshoot. Consider this, any PBM that generates cash flow from ingredient costs and/or earned manufacturer revenue (rebates) increases their clients’ net plan costs. So while I agree with Dr. Miller’s point, it is somewhat misleading.

He did, however, acknowledge that “certain patients get caught in the middle of this, and we have got to figure out how to put guard rails around that.” Setting a maximum pharmacy price could be one such guard rail, he said.

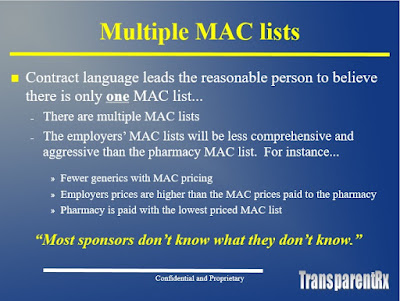

One slide from my “don’t miss” webinar Tuesday October 11 at 3:30 PM ET

|

| Click to Enlarge |

How many businesses do you know want to cut their revenues in half? That’s why traditional PBMs don’t offer a fiduciary standard and instead opt for hidden cash flow opportunities such as multiple MAC lists. Want to learn more?

Register: https://attendee.gototraining.com/rt/3034343502849349634

A snapshot of what you will learn in this 30 minute webinar:

- Hidden Cash flows in the PBM Industry i.e. formulary steering and rebate disguising

- How to calculate cost of pharmacy benefit manager services or CPBMS

- Specialty pharmacy cost-containment strategies

- The financial impact of actual acquisition cost (AAC) and effective acquisition cost (EAC)

Sincerely,

Tyrone D. Squires, MBA

TransparentRx

2850 W Horizon Ridge Pkwy., Suite 200

Henderson, NV 89052

866-499-1940 Ext. 201

P.S. Yes, it’s recorded. I know you’re busy … so register now and we’ll send you the link to the session recording as soon as it’s ready.

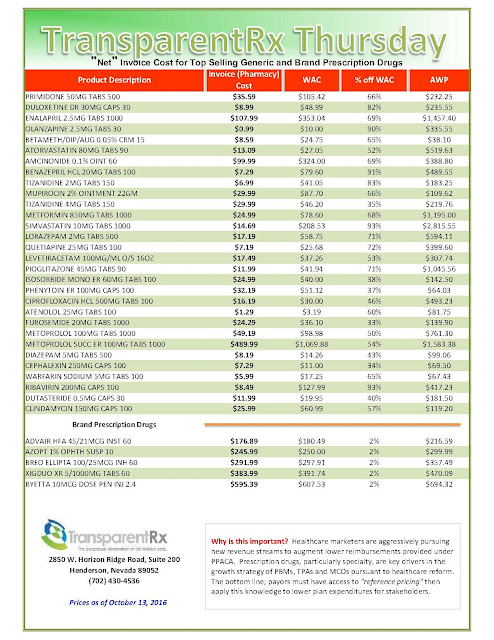

“Gross” Invoice Cost for Top Selling Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs – Volume 138

The costs shared below are what the pharmacy actually pays; not AWP, MAC or WAC. The bottom line; payers must have access to “reference pricing.” Apply this knowledge to hold PBMs accountable and lower plan expenditures for stakeholders.

Step #1: Obtain a price list for generic prescription drugs from your broker, TPA, ASO or PBM every month.

Step #2: In addition, request an electronic copy of all your prescription transactions (claims) for the billing cycle which coincides with the date of your price list.

Step #3: Compare approximately 10 to 20 prescription claims against the price list to confirm contract agreement. It’s impractical to verify all claims, but 10 is a sample size large enough to extract some good assumptions.

Step #4: Now take it one step further. Check what your organization has paid, for prescription drugs, against our pharmacy cost then determine if a problem exists. When there is a 5% or more price differential (paid versus actual cost) we consider this a problem.

Multiple price differential discoveries means that your organization or client is likely overpaying. REPEAT these steps once per month.

— Tip —

Always include a semi-annual market check in your PBM contract language. Market checks provide each payer the ability, during the contract, to determine if better pricing is available in the marketplace compared to what the client is currently receiving.

When better pricing is discovered the contract language should stipulate the client be indemnified. Do not allow the PBM to limit the market check language to a similar size client, benefit design and/or drug utilization. In this case, the market check language is effectually meaningless.

Note: Prices listed herein are gross thus do not account for rebates, discounts or other purchase incentives which ultimately reduces the net cost.

Drugmakers Point Finger at Middlemen for Rising Drug Prices

|

| Click to Enlarge |

But the system has some serious side effects, drug executives and other critics say. Because rebates are based on a percentage of a drug’s list price, PBMs have benefited as the price of drugs has skyrocketed in recent years.

Critics say these rebates also can encourage drug companies to increase prices more sharply than they would have done otherwise. For example, if a drugmaker wants to raise the price it gets for a drug by 6% to drive sales growth and offset research costs, it has to raise the sticker price even more than that to offset the percentage it rebates to PBMs, says Ron Cohen, chief executive of drugmaker Acorda Therapeutics Inc.

Tyrone’s comment: Dr. Cohen hit the nail on the head. Another example, do you believe that a self-funded employer seeking 90 days supply of medication for their employees, from a non-fiduciary PBM’s mail-order pharmacy, for just two months copay really gets that? No, the waiver [one month] is factored back into the payer’s ingredient cost and explains, at least in part, why mail order medications are often times more expensive than retail. Remember, the unique selling position for prescriptions by mail are convenience and lower cost. This scenario is similar to the offset explained by Dr. Cohen as it pertains to rebates.

PBMs deny that they cause drug-price inflation, saying drug costs would be even higher without rebates. “We have every incentive to make costs as low as possible,” said Troyen Brennan, chief medical officer at CVS Health Corp., whose Caremark unit is one the biggest PBMs, along with UnitedHealth Group Inc.’s OptumRx and industry leader Express Scripts Holding Co.

PBMs compete aggressively on price to win business from “very sophisticated purchasers,” Mr. Brennan added.

Tyrone’s comment: It is true 20% of revenue generated by pharmacy benefit managers comes at the hands of some very sophisticated purchasers. However, the remaining 80% of purchasers are subject to ridicule, around the water cooler, about how unsophisticated they are with regard to pricing arrangements and the lack of transparency provided in them yet sign off on the deals. The key to eliminating overpayments is in-depth PBM knowledge and advanced negotiating skills. Otherwise, payers will continue to fall victim like Anthem Inc.

For many years, drugmakers defended the practice of privately negotiating rebates as a market-based alternative to government-run price negotiations. They also prospered under the rebate system, which largely failed to curb drug-price increases.

Pfizer Inc. Chief Executive Ian Read said recently that “the absence of rebates would be healthy for the system.” Drugmakers are paying bigger rebates to PBMs, Mr. Read said at an investor conference, but patients are paying more for prescriptions. “The rebates are being paid, and the copays are going up,” for consumers with drug coverage, he said.

Tyrone’s comment: I tend to agree. For the record, I worked for one of the big five drugmakers Eli Lilly & Co. and can tell you these people weren’t sitting around thinking of ways to take advantage of patients or payers. Sure prescription drugs are often very expensive but they’re not as costly as the hospitalization that would be required if they didn’t exist. I’m likely in the minority on this issue, but sometimes critics of drugmakers act as if drugmakers created the diseases which cause harm to people and then manufactured the drugs to profit from their own creation. In fact the opposite is often true; they develop drugs for which there may be no alternative other than surgery, chronic pain or death in order to prolong life. Having said that, PBMs should not be generating a single penny of revenue for themselves from rebates or any manufacturer revenue. All cost-savings should be passed fully on to payers. Drugmakers want market share and they’re willing to compete against one another, on price and outcomes, without the need for so called “rebates.”

PBMs say they aren’t responsible for rising copays, which are set by health insurers and employers. Express Scripts, the largest PBM, says it advises clients to cap copays for even very expensive drugs at $150.

Tyrone’s comment: So the question is why do you advise clients to cap copays at $150.00? What about co-insurance is there any recommendation on that? Again, the lower the co-pay the more likely a patient fills the brand or specialty prescription from which a non-fiduciary PBM might profit from rebate dollars. Each plan must be evaluated on its own merit not based solely upon what a research study says should be the maximum copay.

“EpiPens are expensive because Mylan raised the price of EpiPens,” Steve Miller, chief medical officer at Express Scripts, said in a recent interview. “To blame it on distributors…is just ridiculous.”

Despite their purchasing power, PBMs have struggled to hold down drug costs. U.S. spending on prescription drugs is estimated to have risen 8% to $321.9 billion last year, compared with a 5.6% increase on all health-care consumption, according to federal data.

Many major drugmakers, meanwhile, have continued to report higher sales, driven in part by price increases.

Criticism of PBMs has accelerated as the industry has consolidated and grown more powerful, while also more-aggressively steering patients to drugs with the largest rebates. The industry’s top three account for three-quarters of the U.S. market—up from 49% in 2011, according to Jefferies LLC. Their combined operating profit was $10.1 billion last year, up 30% from 2013.

Tyrone’s comment: PBMs provide a valuable service and deserve a reasonable return but along the way non-fiduciary PBMs learned they could profit from unsophisticated purchasers who help generate excessive returns. I don’t put all the blame on non-fiduciary PBMs as some of it goes to the payers, and their representation, who permit such a lack of transparency. There is no question if the big three (ESI, Caremark and Optum) switched to a fiduciary model and changed nothing else net plan costs would go down significantly. The only problem is so would their market capitalization by half.

Beyond rebates, PBMs collect other fees based on a percentage of drugs’ prices. PBMs charge drug companies “rebate administration fees” of 2% to 5% of product sales in exchange for tracking the rebates owed to their clients, and providing data on claims that drug companies use to assess market share. PBMs also collect percentage-based fees for distributing high-price drugs through their own mail-order pharmacies.

Express Scripts keeps in aggregate 10% to 15% of rebates, though some clients negotiate to have all rebates passed back to them and pay higher flat fees instead, Everett Neville, Express Scripts’ senior vice president for supply-chain management, said in a January interview.

Tyrone’s comment: This may be true but allow me to shed some light. Some revenue coming from manufacturers to non-fiduciary PBMs aren’t classified as “rebates.” The rebate dollars might be classified as selling or administrative fees for the primary purpose of circumventing the contractual obligation to pass the dollars on to payers. So while a payer might be getting 90% of the rebate dollars it may only be recouping 40% of earned manufacturer revenue, for example. Finally, the rebate process is spearheaded primarily by PBMs not pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Written by Joseph Walker

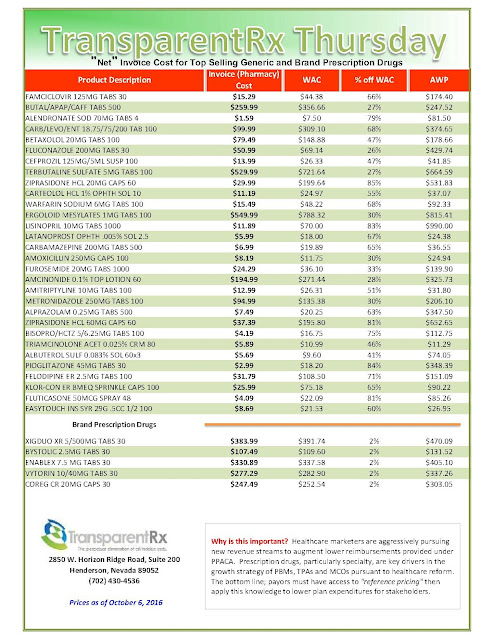

“Gross” Invoice Cost for Top Selling Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs – Volume 137

The costs shared below are what the pharmacy actually pays; not AWP, MAC or WAC. The bottom line; payers must have access to “reference pricing.” Apply this knowledge to hold PBMs accountable and lower plan expenditures for stakeholders.

Step #1: Obtain a price list for generic prescription drugs from your broker, TPA, ASO or PBM every month.

Step #2: In addition, request an electronic copy of all your prescription transactions (claims) for the billing cycle which coincides with the date of your price list.

Step #3: Compare approximately 10 to 20 prescription claims against the price list to confirm contract agreement. It’s impractical to verify all claims, but 10 is a sample size large enough to extract some good assumptions.

Step #4: Now take it one step further. Check what your organization has paid, for prescription drugs, against our pharmacy cost then determine if a problem exists. When there is a 5% or more price differential (paid versus actual cost) we consider this a problem.

Multiple price differential discoveries means that your organization or client is likely overpaying. REPEAT these steps once per month.

— Tip —

Always include a semi-annual market check in your PBM contract language. Market checks provide each payer the ability, during the contract, to determine if better pricing is available in the marketplace compared to what the client is currently receiving.

When better pricing is discovered the contract language should stipulate the client be indemnified. Do not allow the PBM to limit the market check language to a similar size client, benefit design and/or drug utilization. In this case, the market check language is effectually meaningless.

Note: Prices listed herein are gross thus do not account for rebates, discounts or other purchase incentives which ultimately reduces the net cost.

Can ‘Pay for Performance’ Control High Drug Prices?

|

| [Click to Enlarge] |

Can payers save money on increasingly expensive prescriptions by setting prices based not on drugmakers’ wishes, but on how well the medicines control, contain or cure disease?

The notion of tying drug payments to results, called “pay-for-performance pricing” or “value-based pricing,” already is being tested by some health insurance companies, some pharmaceutical companies and Medicare. And just last week, the Oregon Health & Science University announced it will undertake a large-scale research project to examine how states could apply the concept to Medicaid.

Tyrone’s comment: If all the savings are passed-back then great! But, value-based pricing is rife with hidden cash flow opportunities for non-fiduciary pharmacy benefit managers. Traditional or non-fiduciary PBMs are aware of the attention being paid to existing pricing arrangements or overpayments (see ESI, Anthem dispute) so this new pricing arrangement could serve a dual purpose; to show an effort to control costs AND protect their margins. Put another way, pay-for-performance arrangements provide an opportunity for non-fiduciary PBMs to protect margins while giving the “appearance” of reducing drug costs. How will a payer know when a drug has failed and just as important what happens to the revenue when a manufacturer credits it, for example? Remember this, better doesn’t necessarily mean good. The concept is both brilliant and misleading so close the loopholes!

If payers are able to adopt a workable performance- or value-based pricing system on drugs, they may be able to hold down spiraling Medicaid spending, said Matt Salo, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors.

Medicaid, the federal-state health insurance plan for the poor, is staggering under escalating prescription drug prices just as patients and private insurers are, and the costs are straining state budgets. On average, roughly a quarter of a state’s budget goes to Medicaid spending.

Medicaid spending on prescription drugs for Medicaid recipients rose 24.3 percent between 2013 and 2014, in part owing to an increase in enrollment under the Affordable Care Act. That was nearly double the increase in total U.S. prescription drug spending in that same period, according to federal data.

And there’s every reason to think the increase in spending will continue as drugmakers prepare to introduce dozens more “specialty drugs,” high-priced, complex medications developed from living cells to treat chronic conditions such as hepatitis C, HIV, cancer, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis.

Although they barely existed a decade ago, last year specialty drugs accounted for nearly a third of Medicaid spending, or about $16.9 billion. Specialty drugs make up just 1.5 percent of claims, but they could play a big role in the rise of Medicaid spending on drugs.

Something has to give, said Jeff Myers, CEO of Medicaid Health Plans of America, the trade association representing Medicaid managed care plans. “A system in which the manufacturers are pricing to get the most money out of taxpayers isn’t workable,” he said.

Pay-for-Performance

Currently, Medicaid and federal health plans such as Medicare and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs are constrained in bargaining with manufacturers over drug prices.

Pharmaceutical companies enter into agreements with the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services on what drugs all state Medicaid programs will make available to patients. In return, the pharmaceutical companies agree to give the states fixed discounts off their average price.

But those prices are set by the manufacturers, and the manufacturers are not governed by any price ceilings, nor are the prices based on the drugs’ success, such as whether they control or cure a patient’s disease.

Pay-for-performance or value-based pricing would change that. It would tie payments for prescription drugs to their effectiveness, whether they did what they were designed to do.

How well do medications for high blood pressure or cholesterol, for example, keep patients in healthy ranges for each? How well do medications control symptoms of autoimmune diseases? How much do cancer drugs extend life? And how much do the drugs save the health care system by enabling patients to avoid medical treatments they no longer need?

How to Price

Evaluating the effectiveness of a drug will be essential to pricing under the concept. One tool health plans could use for evaluating cancer drugs to establish a price has been developed by the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, in New York.

Called the “DrugAbacus,” the tool creates a price for cancer drugs based on how many years of additional life they provide, the severity of their side effects, the rarity of the disease and the novelty of their chemistry.

“Gross” Invoice Cost for Top Selling Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs – Volume 136

The costs shared below are what the pharmacy actually pays; not AWP, MAC or WAC. The bottom line; payers must have access to “reference pricing.” Apply this knowledge to hold PBMs accountable and lower plan expenditures for stakeholders.

Step #1: Obtain a price list for generic prescription drugs from your broker, TPA, ASO or PBM every month.

Step #2: In addition, request an electronic copy of all your prescription transactions (claims) for the billing cycle which coincides with the date of your price list.

Step #3: Compare approximately 10 to 20 prescription claims against the price list to confirm contract agreement. It’s impractical to verify all claims, but 10 is a sample size large enough to extract some good assumptions.

Step #4: Now take it one step further. Check what your organization has paid, for prescription drugs, against our pharmacy cost then determine if a problem exists. When there is a 5% or more price differential (paid versus actual cost) we consider this a problem.

Multiple price differential discoveries means that your organization or client is likely overpaying. REPEAT these steps once per month.

— Tip —

Always include a semi-annual market check in your PBM contract language. Market checks provide each payer the ability, during the contract, to determine if better pricing is available in the marketplace compared to what the client is currently receiving.

When better pricing is discovered the contract language should stipulate the client be indemnified. Do not allow the PBM to limit the market check language to a similar size client, benefit design and/or drug utilization. In this case, the market check language is effectually meaningless.

Note: Prices listed herein are gross thus do not account for rebates, discounts or other purchase incentives which ultimately reduces the net cost.