Is Your Pharmacy Benefit Delivering Maximum Value? Unpacking the Complexity of Formulary Management

Formulary management can make or break the value of your pharmacy benefit program. It’s a term often tossed around, but many self-insured employers aren’t aware of the intricate mechanics that can either reduce their costs effectively or skyrocket them unnecessarily. Let’s dive into unpacking the complexity of formulary management; what a formulary is, how to assess its impact, and the common pitfalls that employers face when relying solely on rebate-driven solutions.

What Is a Formulary’s Primary Goal and Why Should You Care?

A formulary is a curated list of medications covered by a health plan, carefully designed to balance effective treatment with cost considerations. The primary goal is to ensure patients receive the most appropriate medication for their condition in a cost-effective manner. However, today’s formularies have often moved away from this purpose, transforming instead into a financial tool that prioritizes profit over patient care.

For self-insured employers, understanding what drives these lists is crucial. The choices made during formulary creation can significantly impact patient outcomes, employee satisfaction, and ultimately, your overall healthcare spend.

Evaluating Your Formulary and Utilization Management Program

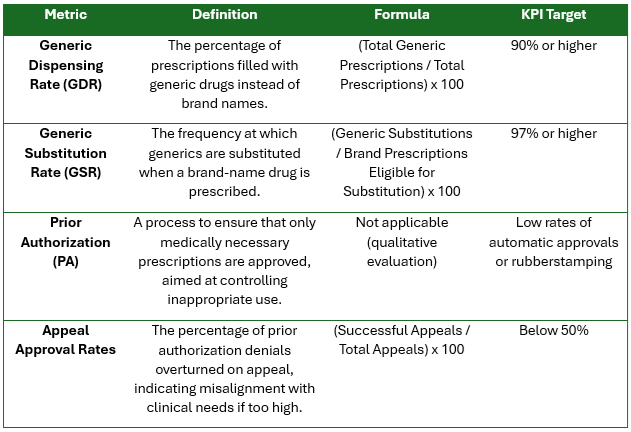

How do you know if your formulary is working efficiently? Evaluating a formulary involves understanding the key metrics that reflect its performance:

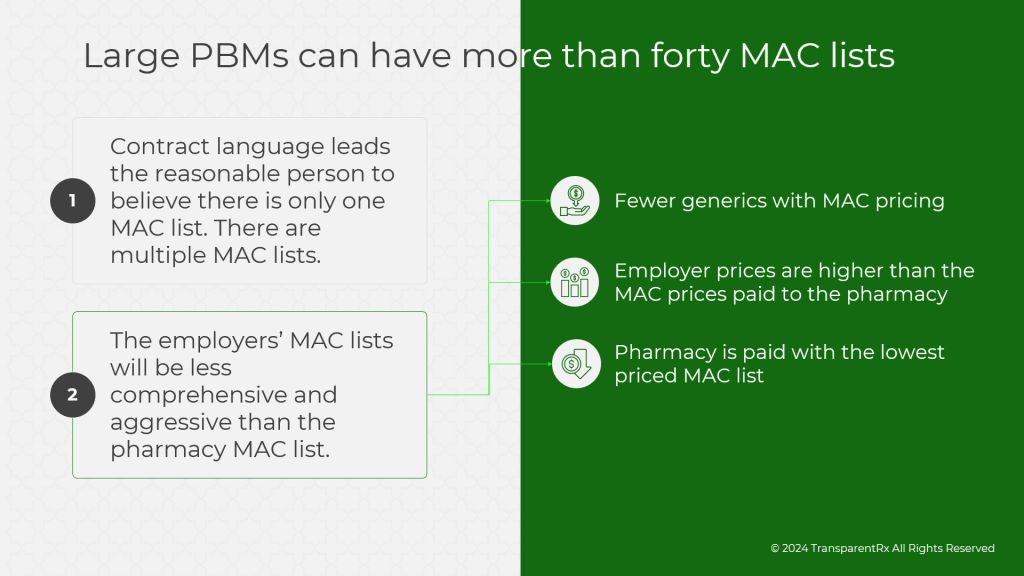

- Generic Dispensing Rate (GDR): This metric shows the percentage of prescriptions filled with generic drugs instead of brand names. Generics offer the same therapeutic value at a fraction of the cost, and a high GDR is often indicative of cost-effective formulary management.

- Generic Substitution Rate (GSR): Similar but distinct from GDR, GSR represents how often generics are substituted when a brand-name drug is prescribed. High substitution rates suggest an effort to reduce costs without compromising quality.

- Prior Authorization (PA): PA requirements are intended to ensure that only medically necessary prescriptions are approved, controlling inappropriate use. However, when PA is rubberstamped or when the PBM owns a specialty pharmacy, it can lead to conflicts of interest and undermine clinical appropriateness. Instead of genuinely evaluating the necessity of a medication, these PAs can become mere formalities, designed to channel prescriptions through the PBM’s specialty pharmacy—often at a higher cost. This practice creates unnecessary hurdles for patients and inflates costs for employers, all while sacrificing the intended clinical oversight.

- Appeal Approval Rates: If many PA denials are being overturned on appeal, it may indicate that the formulary isn’t aligned well with actual clinical needs. When appeals are rubberstamped or primarily exist to protect the PBM’s financial interests, particularly if the PBM also owns the specialty pharmacy, it can mean that the initial denial was never based on clinical reasoning in the first place. High appeal approval rates can signal that the formulary management process is more about protecting profit margins than ensuring patients receive the medications they need.

The Risks of Rebate-Driven Formularies

Rebates sound like a good deal—a way to get money back from manufacturers. But when PBMs prioritize rebates in formulary decisions, it often leads to higher overall drug spend. Why? Because rebate-driven decisions incentivize expensive brand-name drugs over equally effective, cheaper alternatives. These formularies don’t prioritize clinical appropriateness; they prioritize financial incentives, leaving your employees to foot the real costs in the form of unnecessary treatments, side effects, or lack of access to needed medications.

Take, for example, a patient like Joanne, a 49-year-old woman with diabetes. When her medication was removed from the formulary for purely financial reasons, she had to switch treatments—resulting in multiple doctor’s visits, lab tests, and months of discomfort before regaining control of her condition. The real kicker? While the medication switch saved a few dollars on the unit price, the total cost—both financial and human—far exceeded what was saved.

PBM Consultants Overlook Clinical Management—To Everyone’s Detriment

Many PBM consultants or PBCs focus primarily on rebates and discount guarantees when evaluating potential savings, but clinical management is where the real cost control happens. Formularies should be tools for clinical value—not profit generation. By neglecting clinical focus, PBM consultants miss an opportunity to truly manage costs, improve outcomes, and ensure employee health remains the priority.

A clinical-first formulary keeps the patient’s needs in focus, balancing efficacy and cost-effectiveness. When rebates and discounts drive the conversation, you end up managing the price of each pill rather than the value of the overall treatment—often leading to a “penny wise, pound foolish” scenario.

Reclaiming Control—How TransparentRx Can Help

Navigating formulary management is challenging, but it’s not impossible. TransparentRx uses a fiduciary model that guarantees every decision is in the best interest of the patient—and by extension, the employer. By moving away from rebate-driven formularies and aligning formulary decisions with clinical best practices, we help you optimize your pharmacy benefit program, ultimately reducing costs without sacrificing patient outcomes.

With the right approach to formulary management, you can be confident that your pharmacy benefits program isn’t just reducing costs—it’s ensuring your employees have access to the medications they need, without unnecessary hurdles or additional financial burden.