High-cost specialty drugs; predictions for the future

|

| [Click to Enlarge] |

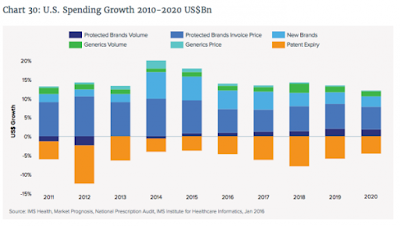

Doug Long, vice president, industry relations for IMS Health, kicked off Thursday morning, April 21, at the Academy of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy Annual Meeting 2016, with his presentation on marketplace trends, “Charting the Course for Change: Industry Update.”

The news is not good: U.S. spending on drugs increased 12.2% to $424.8 billion in 2015, spiking 46 billion over the past year due to higher brand spending and fewer patent expirations; however, spending on brands without exclusivity reduced growth by $14.2 billion in 2015.

On the positive side, net price growth slowed in 2015 to 2.8% as concessions from manufacturers rose sharply. Other metrics from 2015 include: Brands accounted for 11% of prescriptions but drove 73% of sales; prescriptions rose 1% in the last 12 months; diabetes, autoimmune diseases, hepatitis and oncology led the spending growth; specialty new brands continued to spur growth (up 21.5%); and Abilify, Celebrex and Nexium lost patent protection.

Long looked back at 2015 and pointed out the most notable events, which included exclusive launches and price wars for hepatitis C, the arrival of the first biosimilar, Zarxio, and of generic Nexium, rescheduling of controlled substances, the unforgettable price gouging by Valeant and Turing, and merger mania extending into 2016.

As far as specialty goes, 2015 brought more innovation to hepatitis C, along with the emergence of PD1s, PCSK9 inhibitors, orphan drugs, generic Copaxone and more orals, more copayment program cooperation by payers, the patient as payer and more value-driven metrics.

Long predicted that 2016 will continue along the same path with another biosimilar approved, a CMS ruling on Part B reimbursement, a new hepatitis entrant from Merck, new FDA/DEA guidelines on controlled substances, price discussions on orphan drugs and gene therapies and a more-crowded specialty space.

Long said that total prescriptions at chains are expected to far exceed market growth, while mail-order, long-term care and independent pharmacies are going to continue to decline through 2020, at which time, chains could consume a 45.8% share of the market.

By Mari Edlin

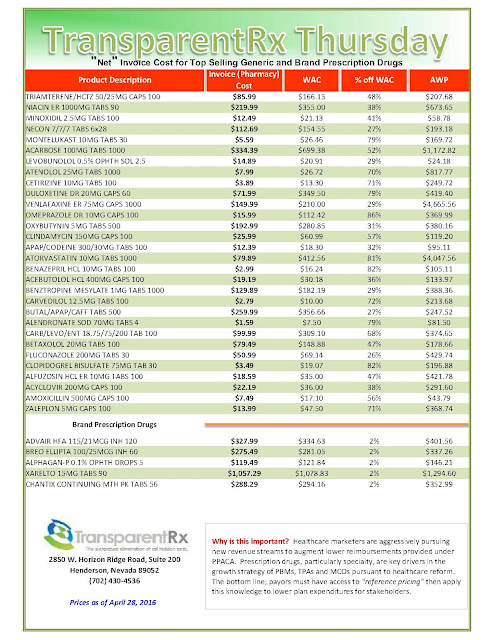

Reference Pricing: “Net” Invoice Cost for Top Selling Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs (Volume 116)

The costs shared below are what the pharmacy actually pays; not AWP, MAC or WAC. The bottom line; payers must have access to “reference pricing.” Apply this knowledge to hold PBMs accountable and lower plan expenditures for stakeholders.

Step #1: Obtain a price list for generic prescription drugs from your broker, TPA, ASO or PBM every month.

Step #2: In addition, request an electronic copy of all your prescription transactions (claims) for the billing cycle which coincides with the date of your price list.

Step #3: Compare approximately 10 to 20 prescription claims against the price list to confirm contract agreement. It’s impractical to verify all claims, but 10 is a sample size large enough to extract some good assumptions.

Step #4: Now take it one step further. Check what your organization has paid, for prescription drugs, against our pharmacy cost then determine if a problem exists. When there is a 5% or more price differential (paid versus actual cost) we consider this a problem.

Multiple price differential discoveries means that your organization or client is likely overpaying. REPEAT these steps once per month.

— Tip —

Always include a semi-annual market check in your PBM contract language. Market checks provide each payer the ability, during the contract, to determine if better pricing is available in the marketplace compared to what the client is currently receiving.

When better pricing is discovered the contract language should stipulate the client be indemnified. Do not allow the PBM to limit the market check language to a similar size client, benefit design and/or drug utilization. In this case, the market check language is effectually meaningless.

Express Scripts generates top-line revenue of $76.63 per claim!

The St. Louis company, now the largest manager of prescription-drug benefits in the U.S., projects profit of $6.31 to $6.43 a share, compared with its earlier view of $6.10 to $6.28 a share.

Meanwhile, for the current quarter, Express Scripts expects adjusted profit of $1.55 to $1.59 a share, compared with analysts’ projected $1.57 a share, according to Thomson Reuters.

|

| Read: Suckers are Beneficial to “Traditional” Pharmacy Benefit Managers — They Cover the Overhead |

The company, which Monday affirmed its projection of 1.26 billion to 1.3 billion in adjusted claims for the year, projects 312 million to 322 million adjusted claims this quarter. Last year, it reported 321.2 million adjusted claims in the second quarter.

Over all, Express Scripts reported a profit of $526.1 million, or 81 cents a share, compared with $441.1 million, or 60 cents a share, a year earlier. Excluding certain items, profit rose to $1.22 a share, at the high-end of the company’s guidance.

Revenue declined 0.4% $24.79 billion, compared with analysts’ projected $25.20 billion, largely tied to Anthem revenue. Adjusted claims rose 5% to 323.5 million, within the company’s range of 315 million to 325 million.

Tyrone’s comment: According to my calculations, Express Scripts generated $76.63 (24.79b / 323.5m) in revenue per claim! This is absurd. Naysayers and homers will justify this number by saying things like, “Express Scripts generates revenue from sources other than prescriptions.” To this I say, “so what!” One performance metric every PBM uses is revenue per claim. If you’re generating so much cash from investment activities why excessively mark-up mail-order prescriptions, for example.

Since the DOD and Anthem are its largest customers and likely pay less, per claim, than say a mid-size employer, my guess is that the per claim revenue for smaller clients is closer to $100 per claim. How does the $76.63 per claim thus inevitable overpayments from plan sponsors happen? In short, much of the revenue is generated from hidden cash flows.

Note: Adjusted claims account for monthly prescriptions filled in retail pharmacies and 90-day fills through the company’s mail-order business.

Game of Thrones: Express Scripts Holding Company Countersues Anthem

|

| [Click to Enlarge] |

Last month, Anthem sued pharmacy benefits manager Express Scripts for more than $15 billion in damages after months of public animosity between the two investor-owned behemoths. Anthem alleged Express Scripts, which negotiates prices with drug makers on behalf of payers and employers, was not passing along enough drug price savings, and Express Scripts therefore was reaping “an obscene profit windfall.”

But Express Scripts countered with a lawsuit of its own filed Tuesday in U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. The PBM denied Anthem’s allegations and elevated the rhetoric, making a messy outcome all but certain.

Anthem and Express Scripts have been working under a 10-year pricing contract since 2009, when Express Scripts agreed to buy Anthem’s struggling in-house PBM for $4.7 billion. Express Scripts offered two scenarios to Anthem, according to the redacted lawsuit: take the $4.7 billion and higher pricing for Express Scripts’ services over the duration of the contract, or take less cash upfront and better pricing over the long term.

Tyrone’s comment —

There is so much dirty laundry being aired to the public. I can’t tell you how much I’m enjoying this battle. Most important here is the $4.7 billion Anthem took upfront instead of securing binding price transparency on the back-end. Now, it is crying foul.

In true Game of Thrones fashion this may have been Anthem’s strategy all along; take the cash and sue later. Considering Anthem knows how the “game” is played and owned a PBM it sold to Express Scripts, the theory makes sense. Or the previous management team could’ve decided to improve the balance sheet (thus higher bonuses) and let the new team deal with the overpayments.

I liken this scenario to self-funded employers who pay a relatively small admin fee upfront, say $.50 – $3.00 per Rx claim, but have not secured binding transparency or better yet a fiduciary standard on the back-end. In this scenario, plan sponsors have essentially written a blank check.

Inevitably, the traditional PBM will augment the low admin fee with hidden cash flows. HCFs (hidden cash flows) can take shape in several ways here are just a few: spreads, rebate attrition, excessive mail-order mark-ups and differential contracting. Here’s the bottom line. Any PBM that claims to be transparent is actually opaque unless it offers either binding transparency or a fiduciary standard. If you’re a plan sponsor or benefits consultant and your client doesn’t have either of these two types of contracts, at a minimum, learn to measure the financial implications of your decision and solutions to right the ship.

“Although Anthem could have passed this upfront money through to its members—in the form of reduced drug pricing—instead, Anthem used the upfront payment to repurchase its stock, which applied upward pressure to Anthem’s stock price, thereby enriching Anthem’s shareholders and management (who held substantial stock options),” Express Scripts argued. In 2009, Anthem, then known as WellPoint, repurchased 57.3 million shares at a cost of $2.6 billion.

Express Scripts also alleged that Anthem is the party that has failed to negotiate new terms in good faith. The current agreement allows Anthem to conduct a market check periodically to see if Express Scripts is obtaining the best prices available for prescription drugs.

Anthem CEO Joseph Swedish told investors this year that an internal analysis showed the insurance company was owed up to $3 billion in savings from Express Scripts. But Express Scripts, according to Anthem, refused to negotiate on new drug pricing terms for more than a year.

Not so, Express Scripts countered. The PBM said it made “five separate counter-proposals to Anthem between June 2015 and March 2016,” all of which were within the $2 billion to $2.8 billion range that Anthem executives had asked for or expected.

“Anthem—under the control of new management—is now improperly attempting to rewrite the PBM agreement, erroneously claiming that it has a right to $13 billion in reduced pricing over the remaining four-year term of the PBM agreement,” the lawsuit reads. “This is simply not true.”

An Anthem spokeswoman released a statement that said Express Scripts’ positions “are without merit. Anthem stands behind the merits of our lawsuit and looks forward to the opportunity to prove the actual facts as the lawsuit moves forward.”

Charles Rhyee, a financial analyst at Cowen & Co., said in a note to investors that Express Scripts’ claims actually are “more convincing” than Anthem’s, noting that the $4.7 billion upfront cash payment “should be taken into consideration.”

By Bob Herman

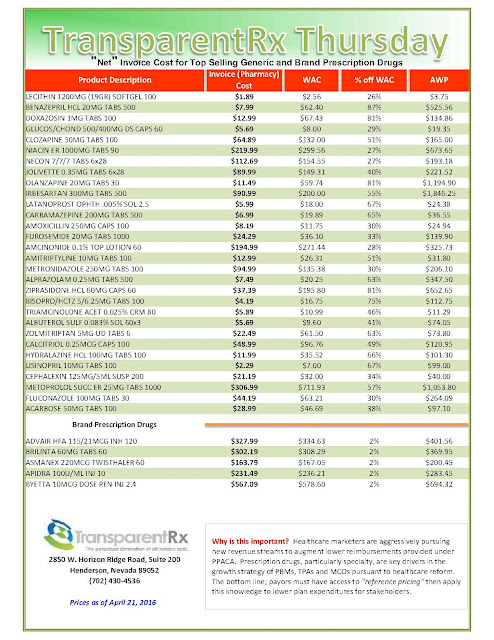

Reference Pricing: “Net” Invoice Cost for Top Selling Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs (Volume 115)

The costs shared below are what the pharmacy actually pays; not AWP, MAC or WAC. The bottom line; payers must have access to “reference pricing.” Apply this knowledge to hold PBMs accountable and lower plan expenditures for stakeholders.

Step #1: Obtain a price list for generic prescription drugs from your broker, TPA, ASO or PBM every month.

Step #2: In addition, request an electronic copy of all your prescription transactions (claims) for the billing cycle which coincides with the date of your price list.

Step #3: Compare approximately 10 to 20 prescription claims against the price list to confirm contract agreement. It’s impractical to verify all claims, but 10 is a sample size large enough to extract some good assumptions.

Step #4: Now take it one step further. Check what your organization has paid, for prescription drugs, against our pharmacy cost then determine if a problem exists. When there is a 5% or more price differential (paid versus actual cost) we consider this a problem.

Multiple price differential discoveries means that your organization or client is likely overpaying. REPEAT these steps once per month.

— Tip —

Always include a semi-annual market check in your PBM contract language. Market checks provide each payer the ability, during the contract, to determine if better pricing is available in the marketplace compared to what the client is currently receiving.

When better pricing is discovered the contract language should stipulate the client be indemnified. Do not allow the PBM to limit the market check language to a similar size client, benefit design and/or drug utilization. In this case, the market check language is effectually meaningless.

Shining a Light on the Dark Practice of Rx Price Gouging

Remember Martin Shkreli, the indicted former CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals, who increased the price of HIV treatment 5,000%, from $13.50 to $750 a pill overnight? How could those who saw his image forget how this villain became even more dastardly when, to avoid incriminating himself, he invoked the 5th amendment, smirking before a congressional committee and tweeting that they were “imbeciles”? Shkreli embodied everything that’s wrong with drug price gouging today.

Remember Martin Shkreli, the indicted former CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals, who increased the price of HIV treatment 5,000%, from $13.50 to $750 a pill overnight? How could those who saw his image forget how this villain became even more dastardly when, to avoid incriminating himself, he invoked the 5th amendment, smirking before a congressional committee and tweeting that they were “imbeciles”? Shkreli embodied everything that’s wrong with drug price gouging today.

Drug profits continue to rise faster than any other healthcare

sector, affecting approximately half of all Americans and 90% of seniors who take a prescription drug. Prescription drug spending spiked 12% in 2014 – the largest increase in a decade – helping the United States maintain the dubious distinction of paying the highest costs for drugs in the world. Prescription drug spending in the US was approximately $457 billion in 2015, or almost 17% of overall health spending. Three-quarters of the public thinks drug costs are too high as drug makers continue to raise prices on branded drugs and cost savings in generics slow.

Many factors drive drug prices. Greed by pharmaceutical executives like Shkreli is only one of them. New medications for hepatitis C drive overall upward costs because they can be used by millions of people. Because they are used by small populations for a short time, specialty drugs for rare or complex conditions do not make as much impact, but still inflate the bottom line.

According to the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development, the cost of developing a prescription drug that gains market approval is $2.6 billion. The drug companies’ argument that R&D costs account for high drug costs is bogus, because much of the basic science research is conducted by government-funded researchers and agencies like the National Institutes of Health. Furthermore, America bears the brunt of development costs for drugs sold across the world, often at significant discounts to what we pay in this country.

Mergers and acquisitions cut competition, allowing drug companies to raise medication prices across the board. Healthcare fraud contributes further to costs, adding almost $100 billion or approximately 10% to annual Medicare and Medicaid spending. The news is full of pharmaceutical manufacturers paying kickbacks to providers, clinics functioning as “pill mills,” and perpetrators recycling drugs by pre-signing thousands of prescriptions for drugs for fake patients, falsifying the records and billing the prescriptions for the fake patients and then reselling the drugs to obtain more reimbursement.

|

| [Click to Enlarge] |

When drug prices escalate, health plans may remove certain expensive medications from their formulary, eventually raise insurance premiums and demand patients pay more out-of-pocket expenses. As medications become pricier, some patients seek cheaper and sometimes unproven alternatives from places like Mexico and Canada, raising safety issues. Others take lower dosages than prescribed. Some patients stop taking their medications altogether, get sicker and face higher medical costs and even the prospect of death.

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services New Plan to Curb Medicare Prescription Drug Price Inflation

The way the Medicare program works now is pretty straightforward: Part B pays the average sales price of a drug plus a 6% add-on. This add-on is what’s designed to cover the costs of care for physicians and their staff. But there’s the idea floating around among the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which is implementing this experiment, that physicians are being influenced to prescribe the most expensive drug rather than the best drug for a patient to garner the biggest add-on possible.

The solution? The new model, which is being tested in select markets, pays the average sales price of a drug while imposing an add-on payment of just 2.5%, plus a flat-fee payment of $16.80 per drug per day. The CMS’s idea behind this change is to see if patient quality and value of treatment can be improved while simultaneously saving Medicare money.

|

| Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services |

Although improved patient quality and value are broad goals of the CMS, there are a few specific strategies they’re targeting. For one, they hope to substantially reduce patient cost-sharing. If physicians opt for those cheaper medications, then the consumer will be on the line for 20% of a much lower cost (Medicare typically covers 80% of qualified medical expenses, with the consumer picking up the remainder).

This experiment would also help the CMS examine indications-based pricing. The CMS would analyze the clinical effectiveness of certain therapies and, based on price as well, weed out what works and what doesn’t so the program only pays for therapies that provide positive results and good value for patients.

Lastly, this model will test the effectiveness of a standard payment rate for groups of similar therapeutic products. No flat fee has been tested like this before — but if effective, it could dramatically lower program costs.

Will it work?

The new plan is a rough draft and in time, with diligence and proper oversight, the finished product is going to eliminate incremental waste. My primary concern is the 2.5% add-on payment. The percentage basis incentivizes manufacturers to jack up prices and physicians to prescribe more costly medications although less costly yet therapeutically equivalent products are on the formulary. A better strategy would have been to add more dollars to the dispensing fee thus completely eliminating the add-on percentage. Simply put, the plan will eventually work.

National Drug Spend | $310B in 2015 and projected to double by 2020

Indeed, the growth rate is supposed to increase each year through 2020, the report says – thanks largely to drugs targeting cancer. “Of the $282 billion of growth over the next five years from branded medicines, $91 billion is forecast to result from new medicines launched during that period, with the largest share coming from oncology,” the report says.

|

| [Click to Enlarge] |

The number of recently approved drugs buoyed the overall spend: Demand for new branded drugs was high. Generics didn’t help offset much of the costs typically spent on branded drugs, though higher rebates and price concessions from manufacturers helped offset these pressures on patients themselves.

Tyrone’s Comment: Last week I spoke with a large self-funded organization who was caught off guard by the rapid cost increases for prescription drugs in the last twenty-four months. The reason they were caught off guard can be explained by how they historically viewed prescription drug costs in the first place; and that is drug costs are “relatively inexpensive” compared to medical costs. This is true if looking solely at percentages and not whole numbers. $10 million is a lot of money but so is $1 million yet if I evaluate the difference by percentage $1 million is only 10% of $10 million. Since drug costs didn’t garner nearly as much attention as medical costs, no one took the time to learn how to effectively manage pharmacy costs. Consequently, PBMs profit greatly from this error and plan sponsors overpay. The key factor in mitigating rising pharmacy costs is strong [insider] PBM industry knowledge.

There are a few major market segments at play here. Specialty medicines proved to be a particularly strong influencer of growth – contributing nearly half, or $150.8 billion, to the medicine costs. And 43 new medicines were launched in 2015 – of which, about a third were orphan drugs. Another 30 brands were launched that weren’t necessarily novel, but served as combination therapies and alternative dosing that further filled the medication landscape.

Advances in precision medicine and biosimilar development were also impactful. These trends will just continue, as more specialty drugs continue to hit the market.

Reference Pricing: “Net” Invoice Cost for Top Selling Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs (Volume 114)

The costs shared below are what the pharmacy actually pays; not AWP, MAC or WAC. The bottom line; payers must have access to “reference pricing.” Apply this knowledge to hold PBMs accountable and lower plan expenditures for stakeholders.

Step #1: Obtain a price list for generic prescription drugs from your broker, TPA, ASO or PBM every month.

Step #2: In addition, request an electronic copy of all your prescription transactions (claims) for the billing cycle which coincides with the date of your price list.

Step #3: Compare approximately 10 to 20 prescription claims against the price list to confirm contract agreement. It’s impractical to verify all claims, but 10 is a sample size large enough to extract some good assumptions.

Step #4: Now take it one step further. Check what your organization has paid, for prescription drugs, against our pharmacy cost then determine if a problem exists. When there is a 5% or more price differential (paid versus actual cost) we consider this a problem.

Multiple price differential discoveries means that your organization or client is likely overpaying. REPEAT these steps once per month.

— Tip —

Always include a semi-annual market check in your PBM contract language. Market checks provide each payer the ability, during the contract, to determine if better pricing is available in the marketplace compared to what the client is currently receiving.

When better pricing is discovered the contract language should stipulate the client be indemnified. Do not allow the PBM to limit the market check language to a similar size client, benefit design and/or drug utilization. In this case, the market check language is effectually meaningless.

- Go to the previous page

- 1

- …

- 109

- 110

- 111

- 112

- 113

- 114

- 115

- …

- 144

- Go to the next page