The ACP’s Health and Public Policy Committee developed these positions and recommendations. This committee is charged with addressing issues that affect the health care of the U.S. public and the practice of internal medicine and its subspecialties.

The committee identified studies, reports, surveys, relevant news articles, policy documents, and other sources of public information on the pricing of prescription drugs; cost of prescription drugs; cost of drugs to patients and payers; and other aspects of the research, development, regulation, and marketing of prescription drugs.

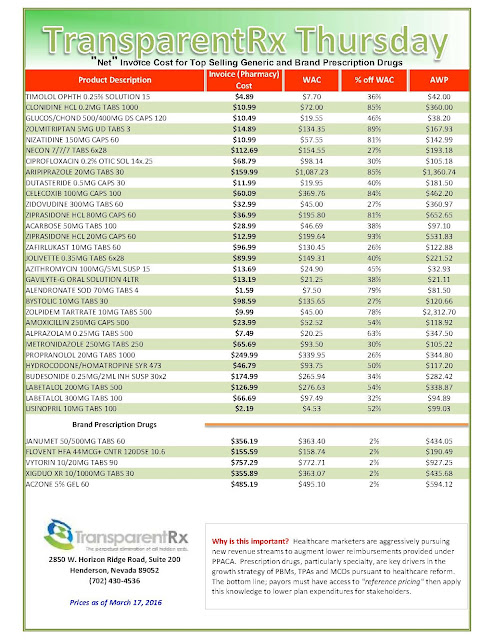

|

| [Click to Enlarge] |

Draft recommendations were reviewed by ACP’s Board of Regents, Board of Governors, Council of Early Career Physicians, Council of Resident/Fellow Members, Council of Student Members, Council of Subspecialty Societies, and outside expert reviews. The position paper and recommendations were reviewed by the ACP Board of Regents and approved on 16 February 2016.

Recommendations

1. ACP supports transparency in the pricing, cost, and comparative value of all pharmaceutical products:

a. Pharmaceutical companies should disclose:

i. Actual material and production costs to regulators;

ii. Research and development costs contributing to a drug’s pricing, including those drugs which were previously licensed by another company.

b. Rigorous price transparency standards should be instituted for drugs developed from taxpayer-funded basic research.

2. ACP supports elimination of restrictions of using quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) in research funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI).

3. ACP supports the following approaches to address the rapidly increasing cost of medications:

a. Allow greater flexibility by Medicare and other publicly funded health programs to negotiate volume discounts on prescription drug prices and pursue prescription drug bulk purchasing agreements (7, 8);

b. Consider legislative or regulatory measures to develop a process to reimport certain drugs manufactured in the United States, provided that the safety of the source of the reimported drug can be reasonably assured by regulators;

c. Establish policies or programs that may increase competition for brand-name and generic sole-source drugs.

4. ACP opposes extending market or data exclusivity periods beyond the current exclusivities granted to small-molecule, generic, orphan, and biologic drugs. ACP supports robust oversight and enforcement of restrictions on product-hopping, evergreening, and pay-for-delay practices as a way to increase marketability and availability of competitor products.

5. ACP supports research into novel approaches to encourage value-based decision making, including consideration of the following options:

a. Value frameworks;

b. Bundled payments;

c. Indication-specific pricing;

d. Evidence-based benefit designs that include explicit consideration of the pricing, cost, value, and comparative effectiveness of prescription medications included in a health plan’s benefit package.

6. ACP believes payers that use tiered or restrictive formularies must ensure that patient cost-sharing for specialty drugs is not set at a level that imposes a substantial economic barrier to enrollees obtaining needed medications, especially for enrollees with lower incomes. Health plans should operate in a way consistent with ACP policy on formularies and pharmacy benefit management.

7. ACP believes that biosimilar drug policy should aim to limit patient confusion between originator and biosimilar products and ensure safe use of the biosimilar product in order to promote the integration of biosimilar use into clinical practice.

Conclusion

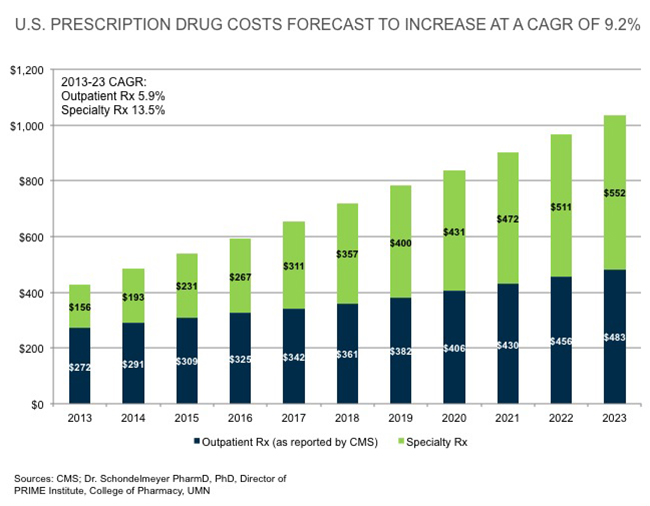

Recent trends show that increases in the price of prescription drugs have drawn the interest and concern of patients, payers, government officials, and physicians, particularly in the cases of very substantial price increases for some generic drugs, and in the price of existing brand-name drugs and specialty drugs (9). The United States often pays more than other high-income countries for the same drugs, and despite discounts, rebates, coupons, and assistance programs, high and increasing drug prices still threaten to keep patients from getting the drugs they need.

Through collaboration and innovation, stakeholders have the ability to effect change by supporting transparency in how drugs are priced, developing and piloting novel approaches to evaluate and pay for drugs through evidence-based practices that reward advancements in the medical field, assuring access to needed prescription medication by not placing disproportionate economic burden on patients, encouraging informed patient participation in their health care decision making, and ensuring a truly competitive marketplace.

Continue Reading >>