Look closely at ads for most medications that appear in magazines, on TV or on the internet. Along with an extensive list of side effects and possible uses, you’ll find an offer to explore options that will make it easier for patients on commercial insurance to afford the expensive meds.

They’re called copayment coupons and cards, discounts and patient-assistance plans. These financial breaks for consumers are part of a $7 billion effort by pharmaceutical firms in 2015—up from $1 billion in 2010—designed to help patients access drugs they otherwise can’t afford, according to IMS Health.

While the coupons have improved patient compliance, drug manufacturers are covering all or part of the copays to bypass efforts by insurers and pharmacy benefit managers to rein in the rising price of drugs. One key strategy is to put lower copays on lower-cost preferred drugs and raise copays on higher-priced medicines that may not offer additional value for their higher cost.

The patient-assistance portion of such drug company programs, designed to help patients access the most expensive meds, represents only 5% to 10% of the $7 billion, according to IMS. The rest goes for coupons.

“Coupons eliminate members’ cost share for high-cost brand medicine, removing the financial incentive for them to choose a lower-cost generic or preferred brand,” said Patrick Gleason, director of health outcomes at Prime Therapeutics, a St. Paul, Minn.-based PBM. “This circumvents formulary design, putting the insurer on the line to pay for more non-preferred brand-name medicine—at a price that is often inflated to recapture manufacturer revenue lost from offering coupons in the first place.”

One example: A patient with rosacea, the common skin disorder, told Modern Healthcare how her dermatologist prescribed Monodox, an oral antibiotic that is generically known as doxycycline monohydrate. The branded version is made by Exton, Pa.-based Aqua Pharmaceuticals.

She said that the medicine would cost $1,200 a month without insurance and $800 a month through her Blue Cross plan. But the dermatologist’s office gave her a one-year copay coupon that whittled her out-of-pocket cost down to $30 a month.

A generic doxycycline monohydrate would cost as little as $41 in the Chicago area, according to GoodRx.com, which conveniently links to coupon offers. Aqua did not respond to a request for an interview. The patient said her dermatologist never mentioned a generic was available. The FDA Orange Book lists over a dozen companies that have the right to manufacture doxycycline monohydrate.

Holly Campbell, senior director of communications at Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, the Washington, D.C.-based trade group, defended copay offset coupons and patient-assistance plans.

“Today, too many patients find that they are facing very high cost-sharing that puts their ability to stay on a needed therapy at risk. Some patients face coinsurance as high as 40%, and it is becoming increasingly common that patients must meet a deductible before any prescription-drug coverage applies. In such cases, patients often are less adherent to therapy, which can lead to long-term problems for patients and the healthcare system,” she said.

Campbell noted that payers have tools, such as copays and step therapy, to prevent patients from accessing certain medicines without first meeting plan protocols. She stressed that the vast majority of all prescriptions—including those eligible for patient assistance—are filled using generics or plan-preferred brands.

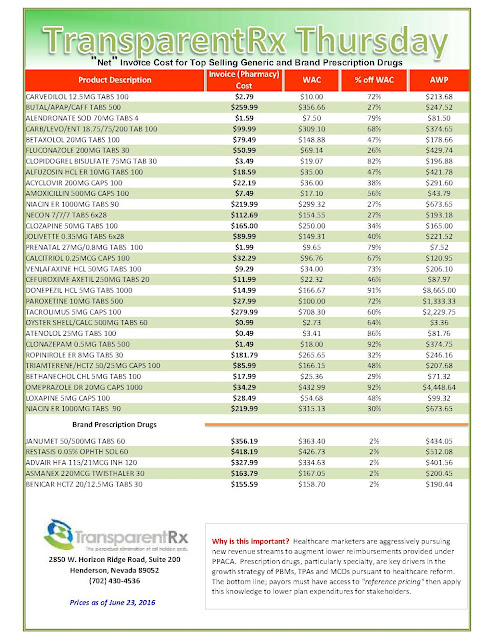

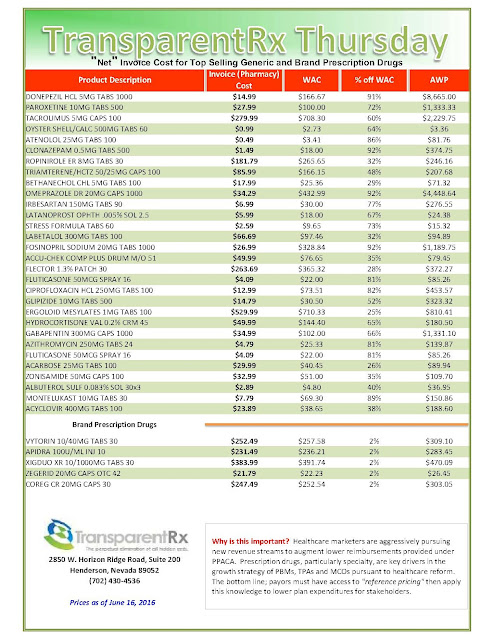

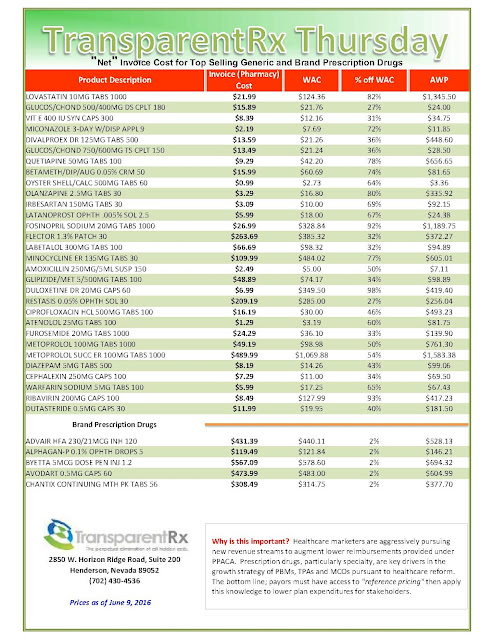

Tyrone’s comment: There are always three sides to a story. In this scenario, we have pharmaceutical manufacturers on one side, PBMs on the other and somewhere in the middle is the truth. Pharmaceutical manufacturers need to start offering more coupons when there isn’t a therapeutically equivalent product available or fewer options. Then the argument “we’re doing this for patients” would have significantly more weight. Next, PBMs should pass-through 100% of all manufacturer revenue (not just rebates) back to the plan sponsor and eliminate profit-taking from network spreads and excessive mail-order mark ups. PBMs would then raise admin fees to offset some of the lost cash flow. Everybody wins including patients and those cutting the checks – plan sponsors! There you have it, the truth.

Couponing is on the rise. In a report released in May, the Boston-based Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development said that there are copay coupons for over 700 medications now, up from about 75 in 2009. IMS Health found that 10% of prescriptions used a copay card in 2015, up from 3% in 2010.

Dr. Joseph Ross, an internist at Yale University School of Public Health, said manufacturers use coupons because they help attract patients and enhance revenue. Ross co-authored an analysis of the phenomenon titled “Prescription-drug coupons—no such thing as a free lunch” in the New England Journal of Medicine in September 2013. Researchers found 62% of coupons (231 of 374) were for brand-name medications for which lower-cost therapeutic alternatives were available.

Crestor (rosuvastatin calcium), which reduces LDL or bad cholesterol and went generic this year, will be the next coupon battleground. London-based AstraZeneca, which makes Crestor, offers coupons that enable patients to pay as little as $3 a month for a drug that retails at about $200 a month. Watson Pharmaceuticals of Parsippany, N.J., received Food and Drug Administration approval for the first generic in April and others are expected.

There’s a lot at stake: Crestor had U.S. sales of $6.3 billion in 2015, ranking it fourth on IMS Health’s list of top-selling medicines in the U.S. Mike Crichton, vice president of cardiovascular at AstraZeneca, offered a humanitarian motive to coupons: “We have to prioritize access and affordability so that patients who need our medicines have access to them,” he said. “We offer savings cards as an option for eligible patients to help reduce the burden of cost at the pharmacy level.”

Ross of Yale said coupons may help individual patients make ends meet, but are harmful to the overall health system and insurance plans that pick up most of the costs.

Eileen Wood, chief pharmacy officer at CDPHP, an Albany, N.Y., not-for-profit health insurance plan, said manufacturers make up every dollar spent on copay coupons and patient assistance plus 20%. “The drug companies are not giving away anything. They have to have a return to their stockholders,” she said. “So if a patient-assistance program is giving $1,000 away, they have to add $1,200 to the cost of the drug.”

To fight back against the tactic, PBMs are beginning to exclude drugs with coupons when cheaper clinically equivalent alternatives are available. “Payers are responding to rising drug costs with new, more restrictive formulary management policies,” said Joshua Cohen, a Tufts health economist. “With prescription-drug spending in the U.S. having grown more than 8.5% in 2015, and projected to continue rising, PBMs are likely to expand their exclusion lists.”

By Howard Wolinsky