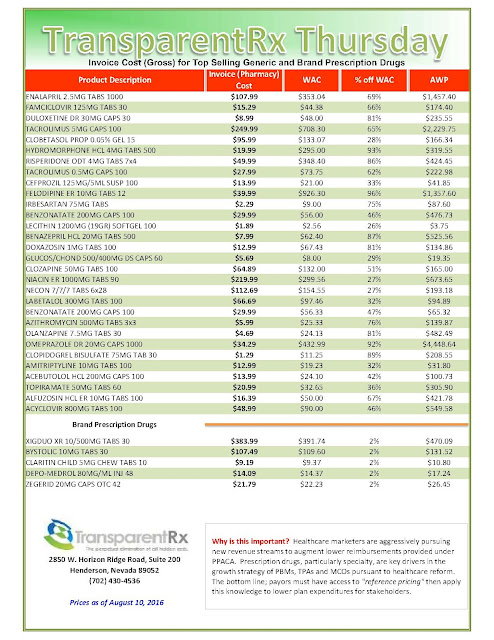

The health insurance industry has successfully generated a robust national discussion of drug pricing in the U.S. However, it is not the complete story. Today, most drug companies offer large rebates to pharmacy benefit managers on behalf of different health plans and employers to reduce patients’ out-of-pocket costs. The problem is a significant portion of the savings is not being passed onto the public.

|

| [Click to Enlarge] |

Until recently, advocates and policymakers had no idea that health plans extract large price discounts on prescription medicines. This changed rather spectacularly when health insurance giant Anthem Inc. and Express Scripts, the nation’s largest PBM, went to war over how much each company was taking in from drug rebates. In litigation Anthem filed in March with the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, the insurer sued Express Scripts for $15 billion in damages, claiming the PBM, which negotiates prices with drug makers on behalf of insurers and employers, is reaping an “obscene windfall” by not passing along enough of the price breaks to Anthem. Express Scripts then countersued in April, arguing Anthem was the one at fault.

Not surprisingly, when two behemoth corporations sue one another, the battle makes national headlines. However, the Anthem-Express Scripts situation has also produced a valuable side benefit: News of the lawsuits shed light on the extent to which pharmaceutical company rebates can lower the costs to health plans and employers for prescription drugs. According to estimates from ZS Associates, a pharmaceutical marketing consulting firm, drug companies pay about $40 billion annually in rebates with the size of the rebate averaging 30 percent of a medicine’s sales.

Realizing these cost savings may not translate into lower copays or cost-sharing requirements for patients, health plan participants and employers have already sued both companies under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, a federal law that requires health plans to act in the best interest of beneficiaries. The first suit, filed in May in the same U.S. District Court, was brought by two HIV patients who paid excessive charges to Express Scripts for needed drugs and seek damages for economic harm.

Then in June, three large employers filed a class action suit on behalf of 26,000 insured workers and their family members, stating these individuals paid too much for their drugs because Express Scripts charged “above competitive pricing levels” and Anthem, in effect, allowed these higher prices as part of its contract with the PBM.

What makes these cases especially interesting is the explanation for the Anthem-Express Scripts dispute. As described in the various complaints, in 2009, Anthem entered into a 10-year contract with Express Scripts in which the insurer was offered a choice of less money upfront but lower pricing for prescription drugs or a large upfront payment with higher prices. Anthem chose higher prices over the course of the contract in exchange for $4.6 billion in upfront fees, which the insurer used to buy back stock rather than passing the savings onto plan participants.

Anthem’s complaint alleges Express Scripts raised drug prices for medicines covered by the Anthem plans and overcharged the insurer as much as $3 billion a year. These actions, according to the two class action suits, left plan participants with “significantly higher” percentage-based co-pays.

In light of what has been revealed and the implications for Americans covered by Anthem health plans, should we expect more lawsuits? This is certainly possible given that Express Scripts supports Anthem’s business in over 24 states and services more than 15 million of its members.

Yet, whatever happens, the Anthem-Express Scripts litigation represents a teachable moment for the public. It is no longer a secret that drug companies pay billions in rebates to PBMs to reduce the price of their medicines. The question is how much of these savings get passed onto insurers, employers, and ultimately consumers. Looking only at the impact on large employers, a recent Pharmacy Benefit

Management Institute survey found about one-quarter of employers received none of the savings from rebates provided to PBMs. A further 30 percent of employers receive flat guaranteed rebate amounts per script. In 2015, these flat guaranteed amounts were $24 per 30-day brand-name prescriptions.

Up until now, there has been almost no scrutiny of the way PBMs manage prescription drug plans for insurers and employers. Clearly now is the time for meaningful change.

STACEY WORTHY | AUGUST 12, 2016

Stacey L. Worthy is the executive director of the Alliance for the Adoption of Innovations in Medicine (Aimed Alliance).