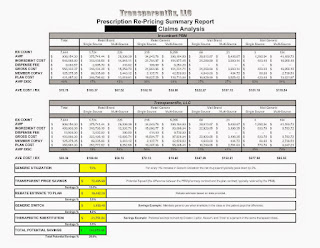

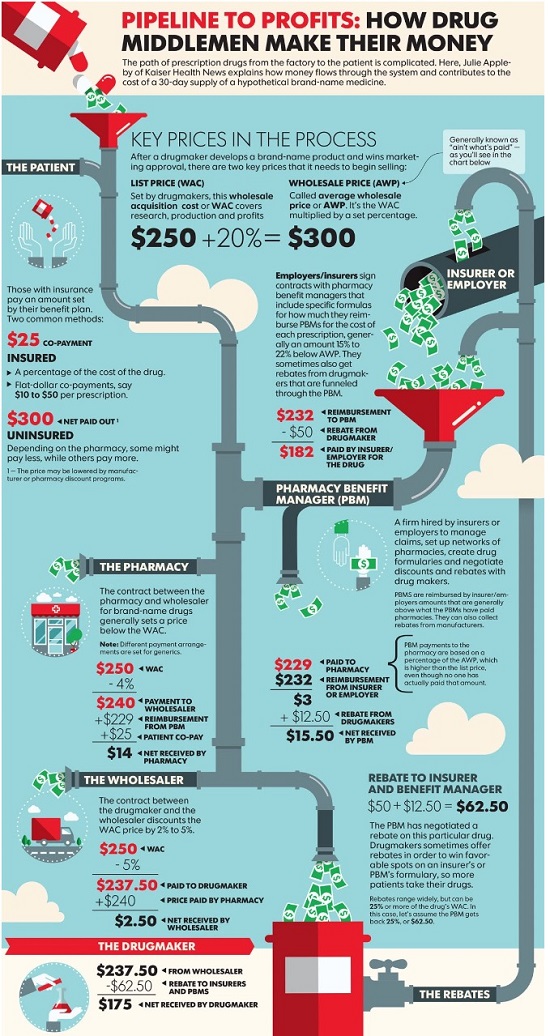

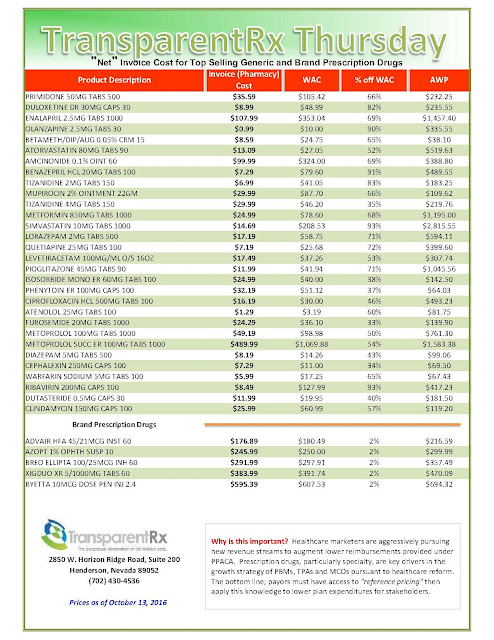

Pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs, oversee drug benefit plans for employers and health insurers. Their job is to hold down the cost of providing those benefits, which they do by choosing which drugs to cover and using that leverage to wrest lower prices from drugmakers through rebates. PBMs keep some of those savings but pass most of it on to their clients.

|

| Click to Enlarge |

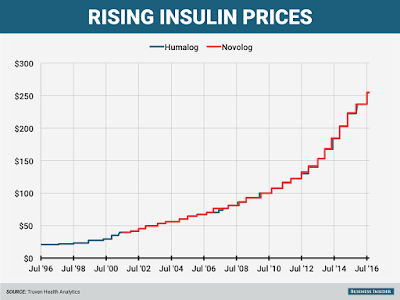

But the system has some serious side effects, drug executives and other critics say. Because rebates are based on a percentage of a drug’s list price, PBMs have benefited as the price of drugs has skyrocketed in recent years.

Critics say these rebates also can encourage drug companies to increase prices more sharply than they would have done otherwise. For example, if a drugmaker wants to raise the price it gets for a drug by 6% to drive sales growth and offset research costs, it has to raise the sticker price even more than that to offset the percentage it rebates to PBMs, says Ron Cohen, chief executive of drugmaker Acorda Therapeutics Inc.

Tyrone’s comment: Dr. Cohen hit the nail on the head. Another example, do you believe that a self-funded employer seeking 90 days supply of medication for their employees, from a non-fiduciary PBM’s mail-order pharmacy, for just two months copay really gets that? No, the waiver [one month] is factored back into the payer’s ingredient cost and explains, at least in part, why mail order medications are often times more expensive than retail. Remember, the unique selling position for prescriptions by mail are convenience and lower cost. This scenario is similar to the offset explained by Dr. Cohen as it pertains to rebates.

PBMs deny that they cause drug-price inflation, saying drug costs would be even higher without rebates. “We have every incentive to make costs as low as possible,” said Troyen Brennan, chief medical officer at CVS Health Corp., whose Caremark unit is one the biggest PBMs, along with UnitedHealth Group Inc.’s OptumRx and industry leader Express Scripts Holding Co.

PBMs compete aggressively on price to win business from “very sophisticated purchasers,” Mr. Brennan added.

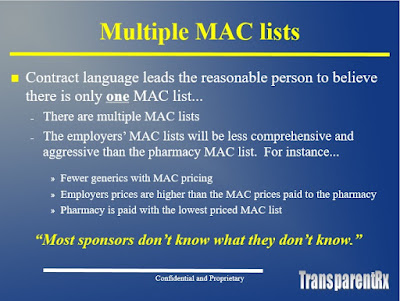

Tyrone’s comment: It is true 20% of revenue generated by pharmacy benefit managers comes at the hands of some very sophisticated purchasers. However, the remaining 80% of purchasers are subject to ridicule, around the water cooler, about how unsophisticated they are with regard to pricing arrangements and the lack of transparency provided in them yet sign off on the deals. The key to eliminating overpayments is in-depth PBM knowledge and advanced negotiating skills. Otherwise, payers will continue to fall victim like Anthem Inc.

For many years, drugmakers defended the practice of privately negotiating rebates as a market-based alternative to government-run price negotiations. They also prospered under the rebate system, which largely failed to curb drug-price increases.

Pfizer Inc. Chief Executive Ian Read said recently that “the absence of rebates would be healthy for the system.” Drugmakers are paying bigger rebates to PBMs, Mr. Read said at an investor conference, but patients are paying more for prescriptions. “The rebates are being paid, and the copays are going up,” for consumers with drug coverage, he said.

Tyrone’s comment: I tend to agree. For the record, I worked for one of the big five drugmakers Eli Lilly & Co. and can tell you these people weren’t sitting around thinking of ways to take advantage of patients or payers. Sure prescription drugs are often very expensive but they’re not as costly as the hospitalization that would be required if they didn’t exist. I’m likely in the minority on this issue, but sometimes critics of drugmakers act as if drugmakers created the diseases which cause harm to people and then manufactured the drugs to profit from their own creation. In fact the opposite is often true; they develop drugs for which there may be no alternative other than surgery, chronic pain or death in order to prolong life. Having said that, PBMs should not be generating a single penny of revenue for themselves from rebates or any manufacturer revenue. All cost-savings should be passed fully on to payers. Drugmakers want market share and they’re willing to compete against one another, on price and outcomes, without the need for so called “rebates.”

PBMs say they aren’t responsible for rising copays, which are set by health insurers and employers. Express Scripts, the largest PBM, says it advises clients to cap copays for even very expensive drugs at $150.

Tyrone’s comment: So the question is why do you advise clients to cap copays at $150.00? What about co-insurance is there any recommendation on that? Again, the lower the co-pay the more likely a patient fills the brand or specialty prescription from which a non-fiduciary PBM might profit from rebate dollars. Each plan must be evaluated on its own merit not based solely upon what a research study says should be the maximum copay.

“EpiPens are expensive because Mylan raised the price of EpiPens,” Steve Miller, chief medical officer at Express Scripts, said in a recent interview. “To blame it on distributors…is just ridiculous.”

Despite their purchasing power, PBMs have struggled to hold down drug costs. U.S. spending on prescription drugs is estimated to have risen 8% to $321.9 billion last year, compared with a 5.6% increase on all health-care consumption, according to federal data.

Many major drugmakers, meanwhile, have continued to report higher sales, driven in part by price increases.

Criticism of PBMs has accelerated as the industry has consolidated and grown more powerful, while also more-aggressively steering patients to drugs with the largest rebates. The industry’s top three account for three-quarters of the U.S. market—up from 49% in 2011, according to Jefferies LLC. Their combined operating profit was $10.1 billion last year, up 30% from 2013.

Tyrone’s comment: PBMs provide a valuable service and deserve a reasonable return but along the way non-fiduciary PBMs learned they could profit from unsophisticated purchasers who help generate excessive returns. I don’t put all the blame on non-fiduciary PBMs as some of it goes to the payers, and their representation, who permit such a lack of transparency. There is no question if the big three (ESI, Caremark and Optum) switched to a fiduciary model and changed nothing else net plan costs would go down significantly. The only problem is so would their market capitalization by half.

Beyond rebates, PBMs collect other fees based on a percentage of drugs’ prices. PBMs charge drug companies “rebate administration fees” of 2% to 5% of product sales in exchange for tracking the rebates owed to their clients, and providing data on claims that drug companies use to assess market share. PBMs also collect percentage-based fees for distributing high-price drugs through their own mail-order pharmacies.

Express Scripts keeps in aggregate 10% to 15% of rebates, though some clients negotiate to have all rebates passed back to them and pay higher flat fees instead, Everett Neville, Express Scripts’ senior vice president for supply-chain management, said in a January interview.

Tyrone’s comment: This may be true but allow me to shed some light. Some revenue coming from manufacturers to non-fiduciary PBMs aren’t classified as “rebates.” The rebate dollars might be classified as selling or administrative fees for the primary purpose of circumventing the contractual obligation to pass the dollars on to payers. So while a payer might be getting 90% of the rebate dollars it may only be recouping 40% of earned manufacturer revenue, for example. Finally, the rebate process is spearheaded primarily by PBMs not pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Written by Joseph Walker