Concerns Persist about the 340B Discount Program

|

| [Click to Enlarge] |

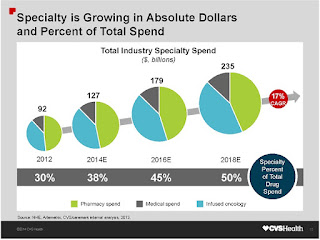

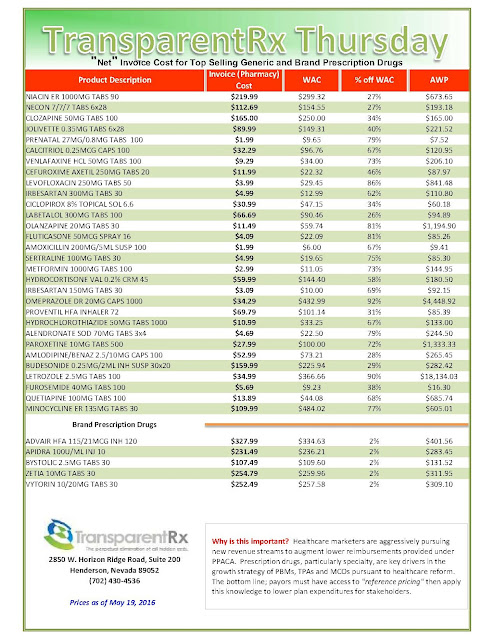

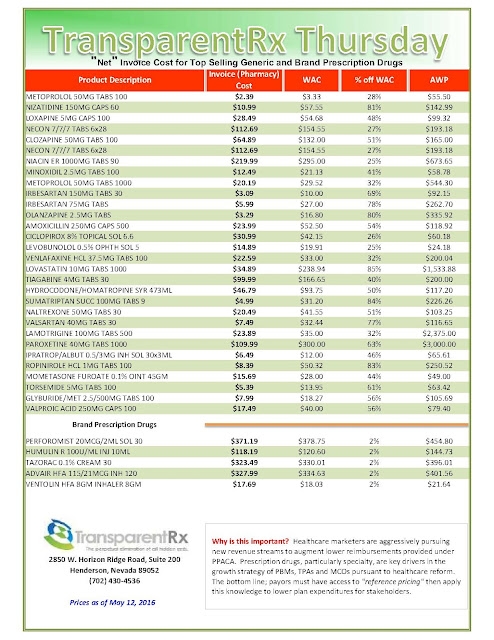

Did you know there is a federal program that provides medicines at a steep discount to some hospitals and clinics? Created in 1992 as part of the Veterans Health Care Act, the 340B drug pricing program requires drug companies to provide discounts—sometimes as much as 50%—to covered entities, hospitals, and clinics that treat low-income and uninsured patients.

Covered entities also include federally qualified health centers and look-alikes, consolidated health centers, freestanding cancer centers, and more. In addition to paying less for the drugs, the covered entities are also permitted to generate profits from the sale of prescription medications to insured patients in order to subsidize required medications for underinsured patients.

Under the 340B program, participating drug manufacturers sign an agreement with the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) stipulating that they will charge covered entities at or below a maximum price, known as the ceiling price.

Typically, pharmacy services provided by a 340B-covered entity may be provided through either an in-house pharmacy or a contract with an outside pharmacy, including a community pharmacy. The thinking is that a community pharmacy might provide real value to a patient and also add an income stream to its existing business model. That is not necessarily so according to a white paper…

“The 340B law’s legislative history makes clear that the intent of the 340B program is to help uninsured indigent patients by giving covered entities that serve high numbers of uninsured indigent patients access to discounts for drugs. Today, however, it is unclear whether this goal is being met even as the program continues to grow dramatically. Evidence suggests that the program has departed significantly from its statutory foundation.”

Medical centers, hospitals, and other covered entities have begun to use the program to boost profits rather than help low-income and uninsured patients. Over the past few years, there have been calls for greater oversight of the program due to complaints that some hospitals are receiving discounted drug benefits disproportional to the small number of low-income patients they serve.

“Hospitals participating in the 340B program aren’t required to pass the discount along to patients or insurers and can subsequently turn a profit by charging the full price for medications the hospital bought at a discount,” according to an article published by Becker’s Hospital CFO.

The study discussed in the article was conducted by Rena Conti, PhD, an assistant professor of health policy and economics in the University of Chicago Departments of Pediatrics and Health Studies, and Peter Bach, MD, director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. They analyzed data from 960 hospitals and 3964 affiliated clinics registered for the 340B program in 2012, along with socioeconomic information on the communities those hospitals and clinics served from the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

“Our findings support the criticism that the 340B program is being converted from one that serves vulnerable patient populations to one that enriches hospitals and their affiliated clinics,” they write in the study.

Tyrone’s comment: Both hospitals and community pharmacies have been making a killing from this program (not all but many) for two decades! Yet none of the cost-savings is being passed-back to plan sponsors. It’s as if the legislation was passed without any consideration for the corporations who fund basically the entire health care system. Having said that, I wouldn’t be surprised if some of the loopholes are closed very soon. One more reason to shift specialty drugs from medical to the pharmacy benefit.

More Questions

The Health Resource and Service Administration’s (HRSA) 2010 guidance, which allowed hospitals to use an unlimited number of neighborhood pharmacies to fill 340B prescriptions, was premised on the expectation that entities contracting with multiple pharmacies would not increase the risk of illegal activities:

(1) diversion of 340B medicines to persons who are not eligible to receive them, and

(2) permitting manufacturers to be charged duplicate Medicaid and 340B discounts for the same drug. HRSA further assumed that entities contracting with multiple pharmacies would adhere to certain program integrity standards. Independent reports by the Government Accounting Office and the HHS Office of Inspector General call into question whether these expectations are being met.

One issue is that the program allows hospitals to use the discounted drugs to treat not only poor patients but also those covered by Medicare or private insurance.

By Nan Myers