Employers Doubling Down on Pharmacy Costs

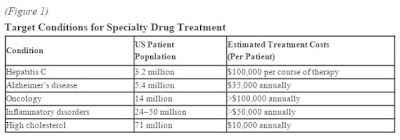

According to a December 2015 report by Towers Watson & Co., now Willis Towers Watson, 53 percent of employers have added new coverage and usage restrictions for specialty prescription drugs, including prior authorization or limiting quantities based on clinical evidence. And another 32 percent are expected to add restrictions by 2018.

Among those companies is 84 Lumber Co. in Eighty Four, Pennsylvania, which launched a prior authorization requirement for compound drugs. Mark Mollico, vice president of human resources said in an email that his company also raised its copayments on specialty drugs and is limiting quantities to a 30-day supply.

|

| [Click to Enlarge] |

84 Lumber, which employs 4,200 people in 250 stores across 30 states, saw its specialty drug spending skyrocket by 94 percent between 2013 and 2014 because of hepatitis C medications. Mollico said specialty drug spending in 2015 accounted for 26 percent of the company’s prescription drug costs, up from 22 percent the previous year.

The 20th annual Towers Watson/National Business Group on Health Best Practices in Health Care Employer Survey also found that more employers plan to exclude certain compound medications from their benefit coverage, with 39 percent having already done so and another 24 percent expected to by 2018. Compounds are drugs that have been mixed or altered, most often by a pharmacist, to customize a medication for a specific patient. The process leads to higher costs, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration might not approve the resulting medication, according to the report.

“In the past five years, you’ve seen almost all employers embrace prior authorization and step therapy, which is a first-line approach,” said Eric Michael, a pharmacy practice leader at Willis Towers Watson in Minneapolis. “Now you are seeing the next evolution with the exclusion of certain compound medications. You can cut costs by 30 percent this way. It’s a much more heavy-handed approach than what you were seeing five years ago, but employers’ bank accounts are only so big.”

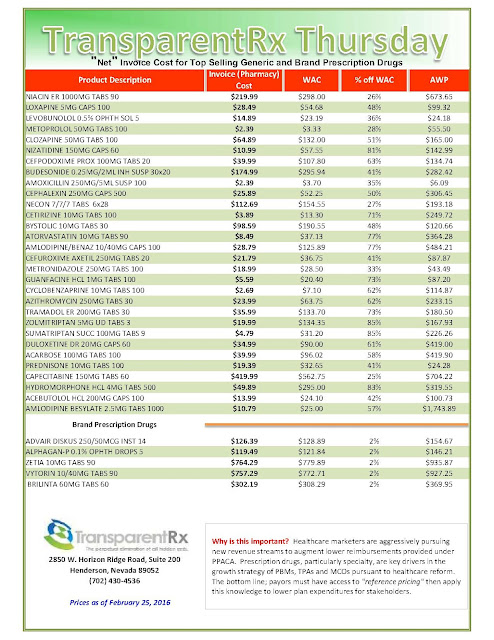

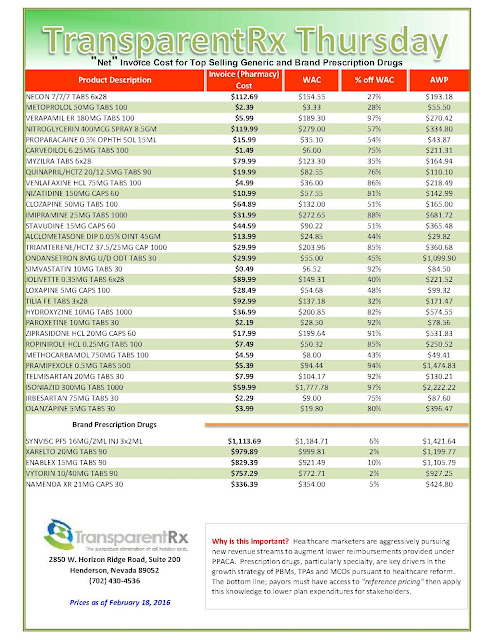

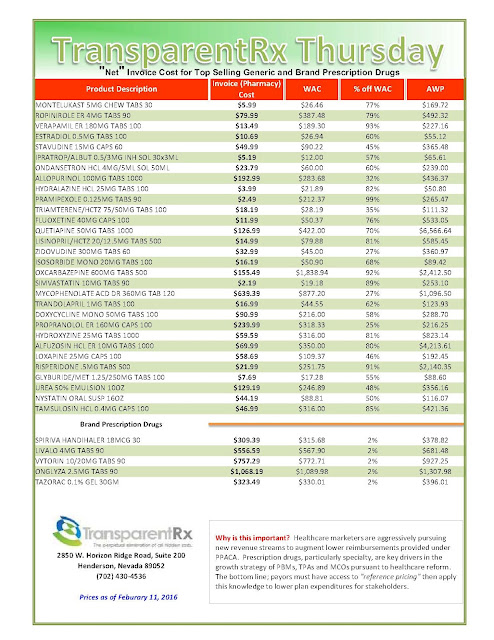

With specialty drug costs expected to grow by 22.3 percent in 2016 compared with 3.9 percent for traditional medications, employers are finding a variety of ways to manage their specialty drug costs, according to a recent report by the NBGH.

In addition to the more common practices of requiring prior authorization under the pharmacy plan, step therapy, which requires patients to try cheaper medications before being approved for costlier options, and limiting quantities based on clinical evidence, employers are also trying other approaches. More than half are using freestanding specialty pharmacies to fill prescriptions and requiring prior authorization under the medical plan in addition to the pharmacy plan, and 35 percent are using price transparency tools for specialty drugs, according to the 2016 NBGH plan design survey report of large employers.

More aggressive tactics are necessary as employers brace for the next wave of blockbuster drugs to hit the market, according to Shari Davidson, the NBGH’s vice president. The most recent class of blockbuster drugs approved by the FDA is PCSK9 inhibitors, which are injectable drugs that treat high cholesterol. A treatment course costs more than $14,000 a year per patient, dwarfing the cost of statins, which are $4 per month, according to the NBGH.

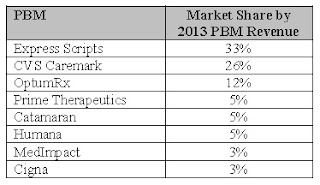

“With each new category of drug that comes out, employers are looking to see which approach makes the most sense,” Davidson said. “Is it prior authorization? Should we work with the PBM [pharmacy benefit manager] or negotiate directly with the manufacturer? As these drugs come out, employers are trying to help employees. There are a ton of oncology drugs that are expected to come out in a year or two. This is what’s keeping benefits managers up at night.”