Employer Health Plans Fear State PBM Crackdown Preemption Threat [Weekly Roundup]

Employer Health Plans Fear State PBM Crackdown Preemption Threat and other notes from around the interweb:

- Employer Health Plans Fear State PBM Crackdown Preemption Threat. Employers looking ahead to a continued push by state and local governments to regulate pharmacy benefit managers more tightly in 2024 are set to back stricter federal law preemption of these measures. PBMs, which manage prescription drug plans of behalf of health insurers, have been criticized over lack of transparency and inflated costs to health plans, but the federal government has not yet enacted legislation to rein in these middlemen. Groups representing companies with self-insured health plans say the states’ attempts to fill the void on PBM legislation threaten preemption protections under the federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act. What’s more, maintaining a nationally uniform regulatory system under ERISA, which turns 50 in 2024, is necessary to avoid a problematic patchwork of state laws, the employer groups say.

- 3 thing to know about specialty pharmacy in 2024. Specialty drugs may be covered by a medical benefit (what patient-members likely think of as “their insurance”) or pharmacy benefits. There’s often a gray area for where specialty falls, but it can relate to whether the drug is being administered in a clinical setting, like a doctor’s office, outpatient clinic, or infusion center. Reimbursement for these drugs can also vary between average wholesale price (AWP) for pharmacy reimbursement and average sales price (ASP) for the medical benefit. It’s complex to compare, and both ASP and AWP are used in the health care industry, but they’re different. ASP is a government-regulated tool that uses manufacturer sales information including discounts, such as rebates. AWP is the average price that wholesalers sell drugs to pharmacies, prescribers, and others. A government report found the median percentage difference between ASP and AWP to be 49%.

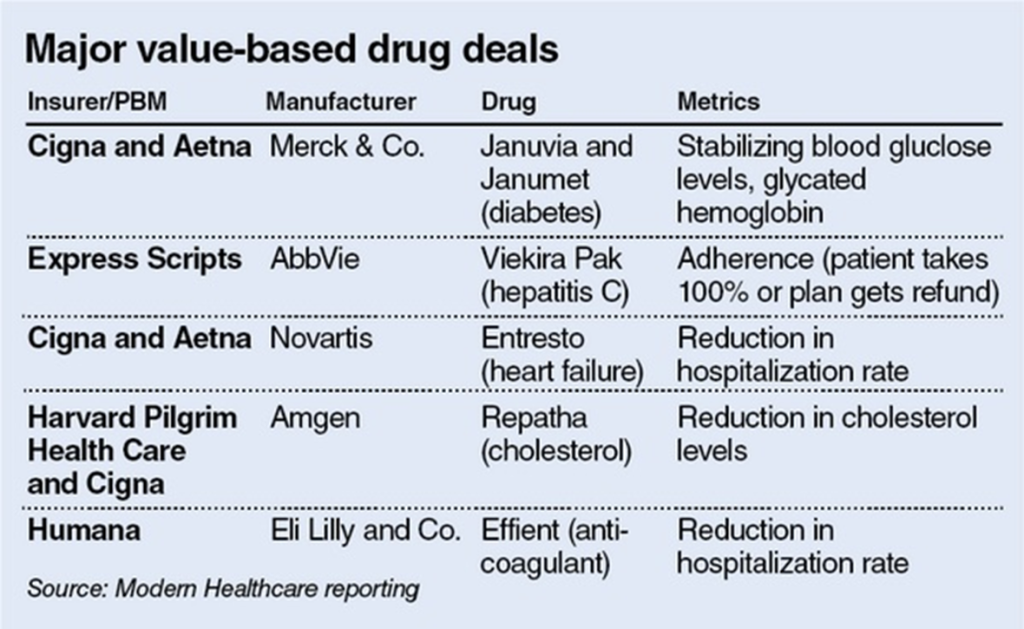

- Plan Sponsors Have a Fiduciary Duty to Employees that Includes Scrutiny of PBM-Owned Rebate Aggregators. Drug manufacturer rebates can be a valuable tool for controlling the rising costs of prescription drugs. Most manufacturers offer a rebate program through which they agree to return a part of the drug’s list price to plans in exchange for access to the plans’ drug “formulary”. Rebates are intended to flow through to the plan sponsors and benefit patients, reducing their overall drug spend. The rebate process has been hijacked by PBMs and their sister-aggregators. PBMs utilize rebate aggregators to negotiate drug manufacturer rebates on behalf of the plans they administer. In 2022, just three PBMs along with their rebate aggregators, controlled 79 percent of the market. Some of the largest rebate aggregators include Zinc (owned by CVS Caremark), Ascent (owned by Express Scripts), and Emisar (owned by United Healthcare).

- Why such ‘high markups’? Senators seek drug price probe of insurers who own PBMs. The senators urged Inspector General Christi Grimm to determine if large insurance companies are using their vertically integrated pharmacies to evade federal requirements that limit the percentage of premium dollars spent on profits and administration, known as the Medical Loss Ratio, or MLR. The letter follows an investigation by the Wall Street Journal revealing significant markups of generic drugs at specialty pharmacies owned by CVS Aetna (which operates the Caremark PBM), Cigna (which owns Express Scripts) and UnitedHealthcare, which owns a PBM and specialty pharmacy. The Journal’s analysis found that the three companies charged up to twenty-seven times more than a generic reference pharmacy for a selection of nineteen drugs. For example, a monthly supply of the generic version of Tarcera, a lung cancer drug, costs $73 at the generic reference pharmacy, compared to $4,409 through Cigna.