In the complex world of healthcare, one aspect that often leaves both patients and healthcare providers frustrated is the prior authorization (PA) process, particularly in the realm of pharmacy benefits management (PBM). The term “prior authorization” refers to the practice of obtaining approval from a healthcare insurer or PBM before a prescribed medication or treatment can be covered by insurance. While the intention behind prior authorizations is to ensure appropriate and cost-effective care, the process has become a profit center, often favoring high-cost drugs over lower cost therapeutic equivalents or alternatives. In this article, we will delve into the intricacies of prior authorizations, discuss the role of electronic prior authorization (ePA) vendors, highlight common pitfalls, and explore ways to measure the effectiveness of this process.

Understanding the Prior Authorization Process

The prior authorization process begins when a healthcare provider prescribes a medication that falls under the coverage of the patient’s insurance plan. The provider submits a request to the PBM or insurer, providing information about the patient’s medical history, the prescribed medication, and the rationale for the treatment. The PBM then reviews the request to determine if the prescribed medication meets certain criteria for coverage, such as medical necessity, cost-effectiveness, and formulary compliance. If the PBM approves the request, the medication is covered by insurance. If not, the healthcare provider may need to explore alternative treatments or submit additional documentation to support the request.

The Role of Electronic Prior Authorization (ePA) Vendors

To streamline and expedite the prior authorization process, many healthcare organizations have turned to electronic prior authorization (ePA) vendors. These vendors provide digital platforms that enable healthcare providers to submit prior authorization requests electronically, reducing the reliance on paper-based forms and fax machines. ePA vendors also offer real-time communication between providers and PBMs, making it easier to track the status of requests and receive timely decisions.

CoverMyMeds, a leading electronic prior authorization (ePA) vendor, has grown to become one of the largest ePA platforms, serving as a bridge between healthcare providers, pharmacies, PBMs, and insurers. CoverMyMeds was acquired by McKesson Corporation in 2017. McKesson is a large healthcare services and pharmaceutical distribution company. Commonsense suggests drug wholesalers, like McKesson, want to get drugs out of their distribution centers as fast as possible. PA denials are inconsistent with drug wholesaler inventory turnover goals, for instance. Second to Optum’s acquisition of Change Healthcare, McKesson’s acquisition of CoverMyMeds is the largest conflict of interest in the pharmacy benefits management industry. The third most significant conflict of interest are non-fiduciary PBMs or their parent companies which own mail, retail and/or specialty pharmacies.

Common Pitfalls of the Prior Authorization Process

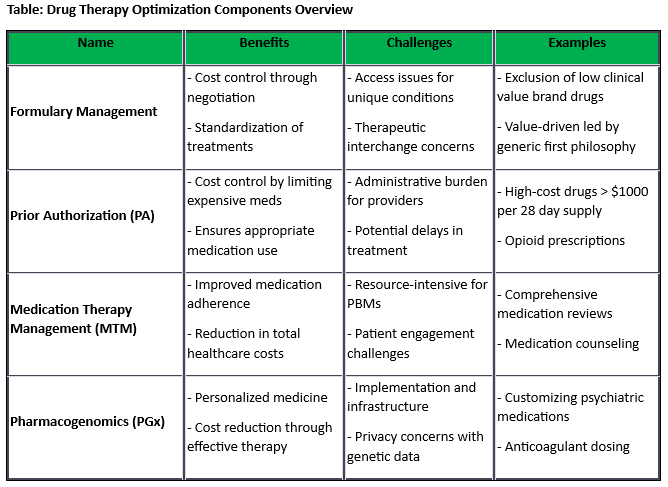

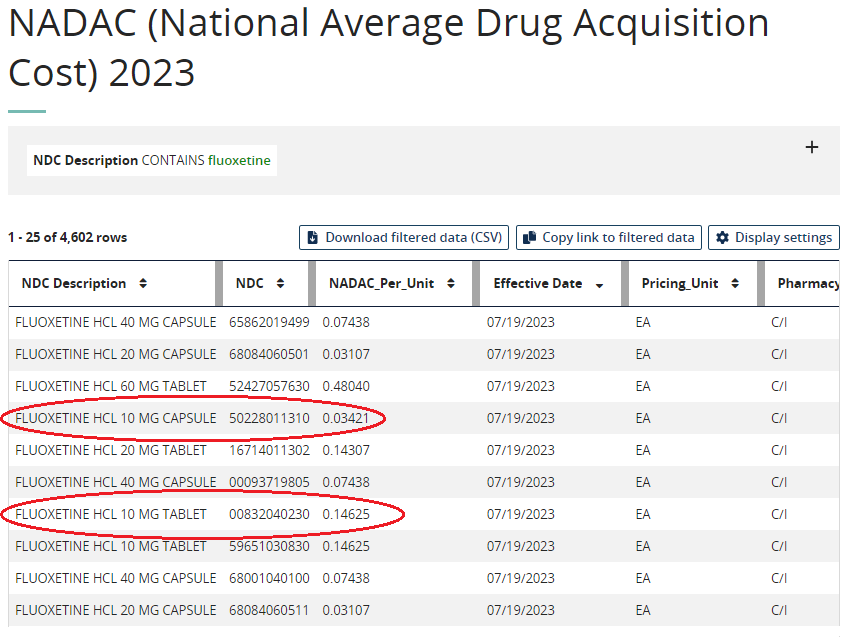

Despite the potential benefits of ePA vendors, the prior authorization process still faces several challenges. One of the most significant criticisms is the role of non-fiduciary PBMs. These PBMs are responsible for managing prescription drug benefits on behalf of insurers and employers, but they also have financial incentives that can conflict with patient care. Critics argue that non-fiduciary PBMs may prioritize revenue over cost-effectiveness, leading to low clinical value drug prior authorization (PA) approvals, for example. A “low clinical value” or LCV drug refers to a medication or treatment that provides limited or minimal therapeutic benefit to patients in relation to its cost, potential side effects, or overall impact on health outcomes.

Additionally, the PA process can be time-consuming for healthcare providers. The administrative burden of submitting requests, gathering documentation, and waiting for decisions can detract from valuable time that could be spent with patients. Delays in obtaining prior authorization can also lead to disruptions in treatment plans, affecting patient outcomes.

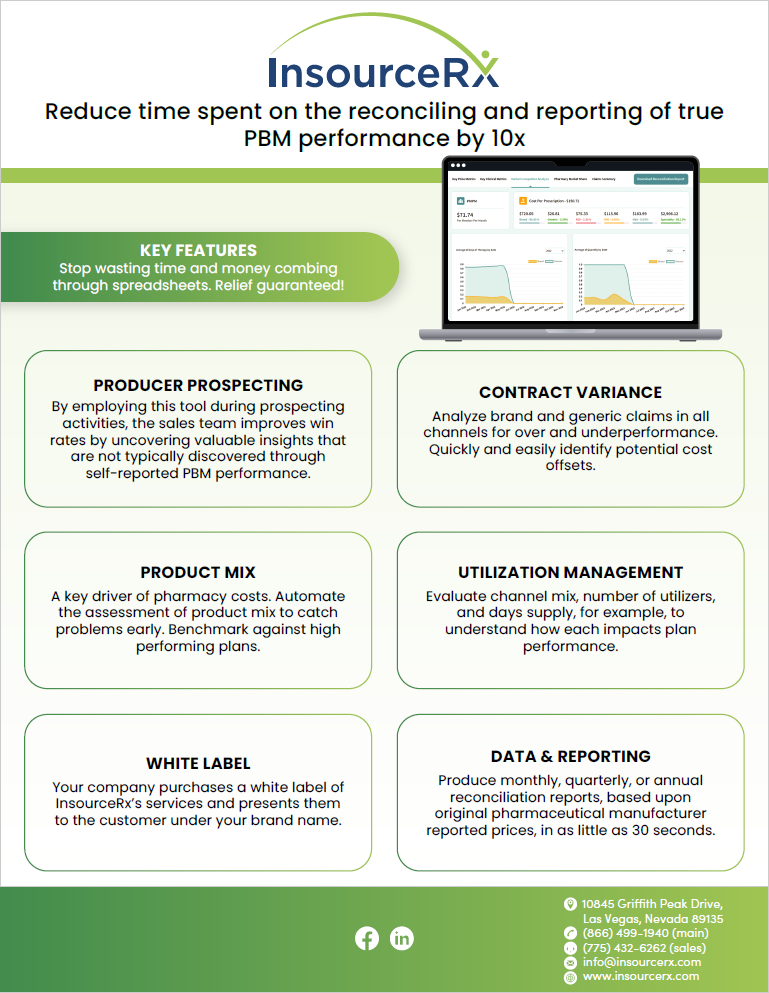

Measuring the Effectiveness of Prior Authorizations

To determine the effectiveness of the prior authorization process, several key metrics can be considered:

- Timeliness: The time taken for a PBM to review and respond to a prior authorization request is a crucial factor. Delays in approvals can impact patient care, especially for acute conditions. Assuming all necessary documentation is received from a provider, 24 hours is a reasonable turnaround time for PA decisions.

- Approval Rates: Measuring the percentage of prior authorization requests that are approved provides insights into the accessibility of both necessary and unnecessary treatments. PA approval rates greater than 70% signal rubberstamping. Cost-effective PA evaluation criteria must incorporate checks for lower cost therapeutic alternatives, FDA approved labeling, patient selection criteria, and clinical trial check points.

- Appeal Rates: Tracking the number of appeals submitted by healthcare providers can indicate the level of dissatisfaction with prior authorization decisions. However, appeal approval rates above 70% signal rubberstamping especially when first and second level appeals are evaluated by the same PBM who stands to gain from LCV high-cost drug PA approvals.

- Patient Outcomes: Monitoring patient outcomes after receiving treatments that required prior authorization can reveal whether the process affects health improvements. Medication Therapy Management (MTM) is a comprehensive approach to optimizing a patient’s medication regimen by ensuring safe, effective, and appropriate medication use, often involving pharmacist consultations and reviews of medication plans. It aims to improve patient outcomes and reduce medication-related problems.

Conclusion

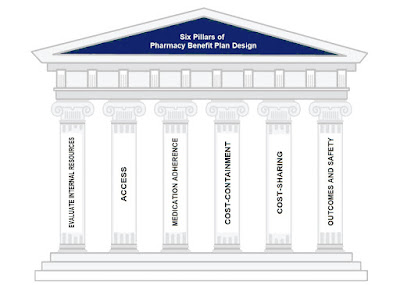

A prior authorization (PA) is a well-intentioned mechanism to ensure cost-effective and appropriate healthcare. However, the process has become convoluted, and the involvement of non-fiduciary PBMs has raised concerns about potential conflicts of interest. The rise of electronic prior authorization vendors offers hope for a more streamlined process, but challenges persist. Prior authorizations are critical in utilization management programs yet plan sponsors and their advisors often take them for granted. The $50 fee per PA belies their impact on patient outcomes and costs for both members and the plan. A self-insured group with 2,500 members could easily achieve incremental savings of $500k annually with cost-effective PA and appeal processes alone.

As the healthcare industry continues to evolve, finding a balance between cost containment and patient-centered care will be essential. Whether through increased transparency, more standardized criteria, or a shift toward fiduciary PBMs, the goal should remain focused on delivering timely and cost-effective drug treatments to those in need.