In the middle of the EpiPen news cycle, CNBC interviewed Steve Miller, the chief medical officer of Express Scripts. “If she wanted to lower the price tomorrow she could,” Miller said of Mylan’s CEO, Heather Bresch. He continued (emphasis added):”We love transparency for our patients. Our patients should know exactly what they’re going to pay when they go to the pharmacy counter. We love transparency for our clients — they can come in. They can audit their contracts. They know exactly what they’re going to be required to pay … What we don’t want is transparency for our competitors.”

Did you catch that?

Express Scripts will tell clients how much they should pay, but it is trying hard not to tell anyone how much things cost. The problem is that when people find out, they seem to get very angry.

Tyrone’s comment: There are two important take aways from the point made above. First, plan sponsors and their agents are not getting enough information to make sound business decisions. Second, once an appropriate amount of information is gathered these same stakeholders must be able to adeptly interpret it. The problem here is most plan sponsors don’t know what they don’t know. One solution, become an expert steward of the pharmacy benefit.

Pharmaceutical-benefit managers started simply enough. In the 1960s, they served a need. As more Americans started taking prescription drugs, insurance companies were overwhelmed processing claims. PBMs offered to do it for them. PBMs pioneered plastic prescription cards and mail-order drug delivery.

They promised Americans they’d negotiate to keep drug prices down. They promised insurers they’d make processing prescriptions a lot cheaper and easier. And they promised drug companies they would favor certain drugs in exchange for rebates and price breaks.

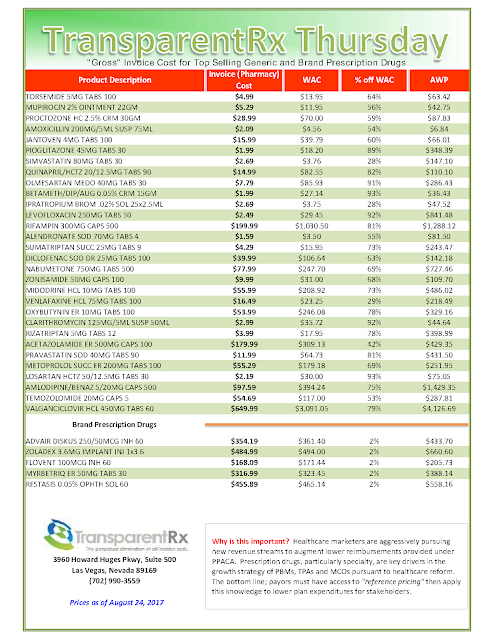

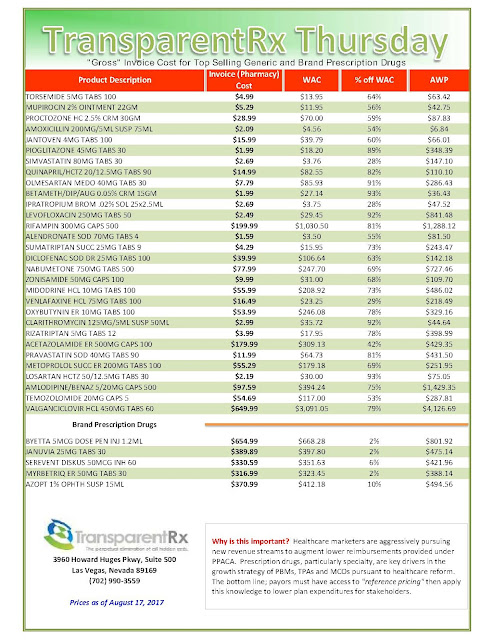

They’re paid fees by the insurers and employers who use their services. But they’re also taking a cut of every sale. That alone isn’t a problem. American business is full of middlemen, and nothing the PBMs do is illegal.

But where the PBMs are starting to get into trouble is that they’re making bundles by keeping each player they deal with — pharmacies, insurers, drugmakers — partly in the dark. And those bundles, you could argue, are coming at the expense of the people who pay for healthcare.

Here’s how a PBM like Express Scripts controls information and pricing.

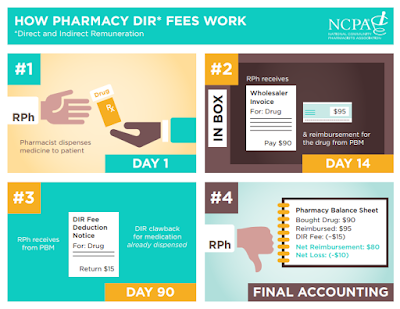

Let’s say a doctor prescribes you a heartburn drug. Its list price is $300, but the only people who pay that are those without insurance. Because you have insurance, you go to your local pharmacy and pay a $20 co-pay. For you, that’s it. Your insurer might be paying $180 for the drug as part of a large-scale agreement it came to years ago via the PBM. The pharmacy that dispenses it may get only $160 for it. That $20 difference is a spread, and that goes to your PBM as profit. That’s on top of fees your insurer is paying the PBM to administer its prescription-drug program.

That’s the simplest way this goes down.

All the while, the pharmacy has no idea how much your insurer is paying for the drug, and your insurer isn’t exactly sure how much the pharmacy is getting for dispensing the medicine. The drug company, meanwhile, isn’t even getting close to the $300 list price that makes everyone so angry.

Then things get really murky.

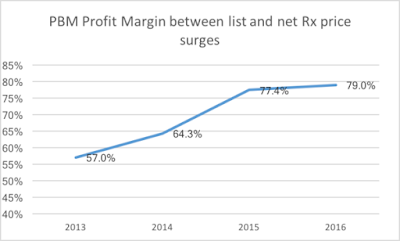

If the price of the drug has increased, the PBM can be paid a rebate for the excess, which it pockets. The insurer, which is paying for the drug, won’t know. “These rebate amounts are less likely to be explicitly shared with a client,” analysts at AllianceBernstein, an investment firm, wrote in a recent note on Express Scripts.

[Read More]