In today’s rapidly evolving healthcare landscape, managing pharmacy benefits is not just about containing costs—it’s about crafting a synergy of quality care, accessibility, efficiency, and participant satisfaction. At TransparentRx, we understand that every aspect of pharmacy benefit design can significantly impact the health and well-being of the participants it serves. Let’s delve into the four broad issues that underpin an effective pharmacy benefit design.

1. Quality: The Pillar of Care

Quality in pharmacy benefits is threefold: care structure, processes, and outcomes. A robust care structure is foundational, ensuring that participants have access to essential medications without unnecessary delays or hurdles. The process, from prescription to pill delivery, must be streamlined, clear, and consistently monitored for potential improvements.

Outcomes are the ultimate measure of quality. At TransparentRx, we prioritize the clinical effectiveness of the medications provided and the positive health outcomes for the participant. This includes not only the resolution of the condition being treated but also monitoring for potential drug abuse, interactions, and side effects.

2. Accessibility: Removing Barriers

Accessibility goes beyond the physical availability of medications. It encompasses the elimination of financial, transportation, and geographical barriers that participants may face. TransparentRx champions affordable options without sacrificing quality. Whether it’s negotiating better prices or embracing mail-order services, we ensure that medications are within reach, both geographically and financially.

Transportation and geographical challenges are addressed by a network of pharmacies and the use of innovative delivery methods. By enhancing our telehealth and mail-order services, we bring the pharmacy to the participant’s doorstep, no matter where they live.

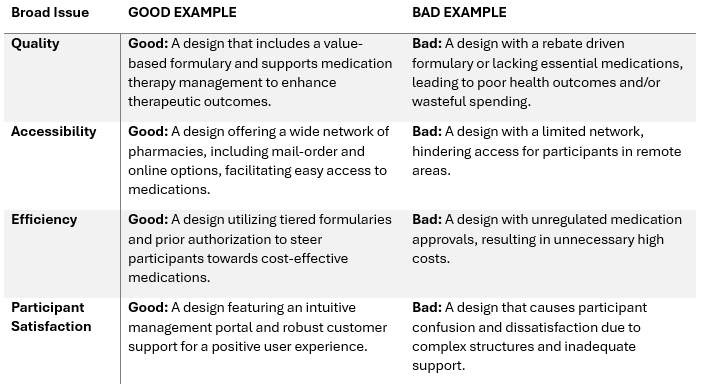

Understanding the distinctions between effective and ineffective benefit design practices is crucial. Below, we present a table contrasting strong (good) examples of benefit design with practices that should be avoided (bad) for each of the four broad issues:

By recognizing the stark contrast between these examples, employers, brokers, and consultants can more effectively evaluate and select pharmacy benefit plans that align with the fiduciary standard of care and participant-centric values. TransparentRx stands ready to guide you through the intricacies of these issues, ensuring that your pharmacy benefit design is both cost-effective and highly beneficial to your participants.

3. Efficiency: Maximizing Resources

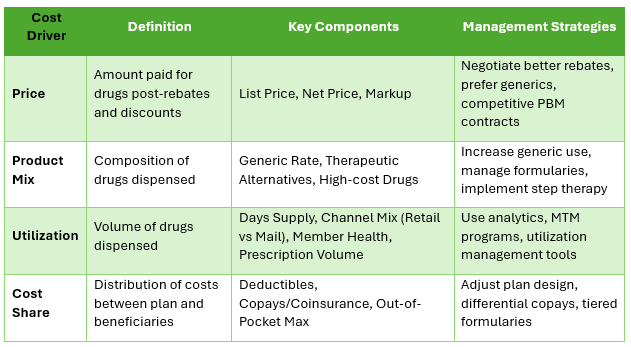

Efficiency in pharmacy benefit design means accomplishing plan objectives with the least expensive combination of resources—without compromising on quality. At TransparentRx, we leverage InsourceRx data analytics to understand usage patterns, eliminate waste, and prevent fraud.

We assess the therapeutic equivalents and generic options, ensuring the most cost-effective medications are available. By balancing the cost against clinical effectiveness, we provide a plan that respects both the participant’s health and the bottom line.

4. Participant Satisfaction: The Heart of Our Mission

The true measure of a successful pharmacy benefit design is participant satisfaction. It reflects the ease of using the plan, the quality of the interactions with pharmacy staff, and the clarity of information provided. TransparentRx takes pride in our Net Promoter Score (NPS) of 86, which is a testament to our commitment to participant satisfaction.

This score significantly surpasses the industry average NPS for pharmacy benefit managers, reflecting the exceptional experience participants have with our services. An NPS of 86 indicates that a vast majority of our clients are not just satisfied, but are enthusiastic advocates for our brand, confident in recommending our services to others.

Conclusion

Pharmacy benefits management is a complex, multifaceted endeavor. By focusing on quality, accessibility, efficiency, and participant satisfaction, TransparentRx crafts a pharmacy benefits plan that not only meets but exceeds expectations. Our commitment to a fiduciary standard of care ensures that every decision we make is in the best interest of the participants we serve—helping our nation look better, feel better, and live longer.