PBM Copay Accumulator Programs: Employers Must Prepare for Changes

PBM copay accumulator programs are a relatively recent development in the health insurance industry, particularly in the United States. These programs have significant implications for patients, especially those requiring expensive, specialty medications. Copay accumulator programs are policies implemented by some health insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBM). Under these programs, any payments made by a third party (such as a drug manufacturer’s copay assistance program) do not count towards a patient’s deductible or out-of-pocket maximum.

Understanding Copay Accumulator Programs

- Patients who rely on manufacturer copay assistance to afford expensive medications find themselves facing higher out-of-pocket costs once the assistance is exhausted. This can happen mid-year, leaving patients suddenly responsible for large expenses.

- The increased cost burden can lead to non-adherence to medication regimens, as patients may skip doses or stop taking medications due to cost.

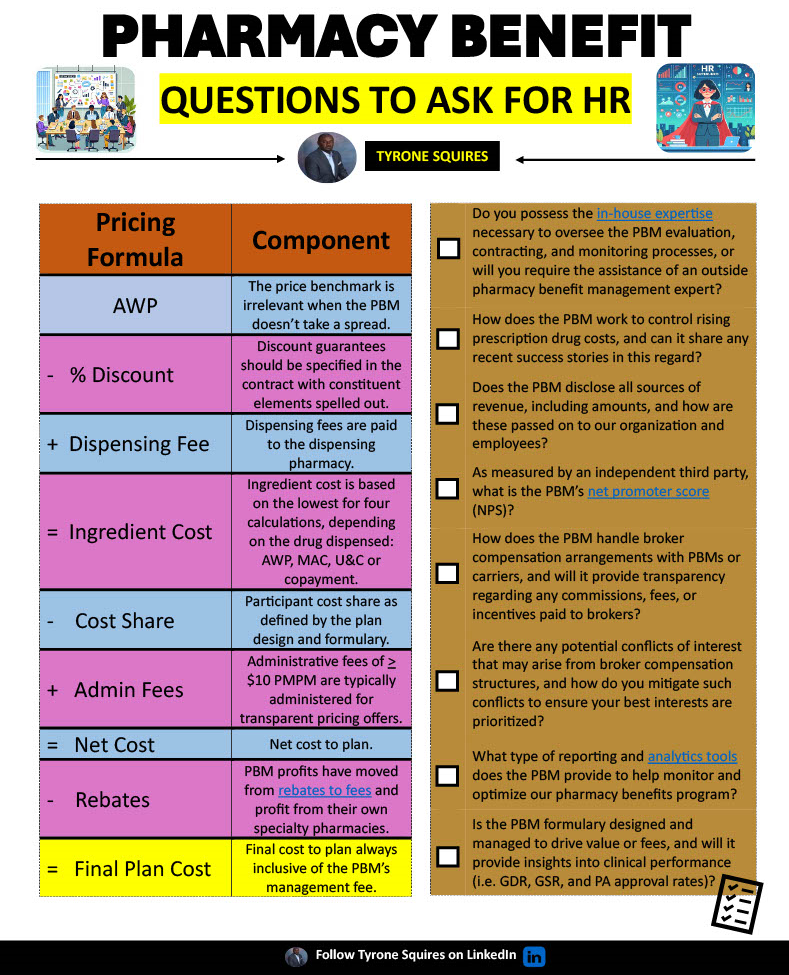

The Role of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs)

PBMs, who manage prescription drug benefits on behalf of health insurers, play a crucial role in the implementation of copay accumulator programs.

- PBMs may have financial incentives to promote copay accumulator programs. By not allowing manufacturer assistance to count towards deductibles, they effectively extend the period during which patients pay out-of-pocket, potentially increasing the PBMs’ share of drug costs covered by patients.

- PBMs may use the existence of manufacturer assistance programs as leverage in price negotiations with drug manufacturers, arguing that these programs reduce the effective price of drugs.

- Employers, especially those providing self-funded health insurance plans, are often persuaded by PBMs to adopt copay accumulator programs. PBMs may present these programs as cost-saving measures.

- There is often a lack of transparency in how PBMs communicate the impact of these programs to employers and, subsequently, to the employees. This lack of clarity can lead to unexpected expenses for patients who are unaware of the program’s details.

How Copay Accumulators Work

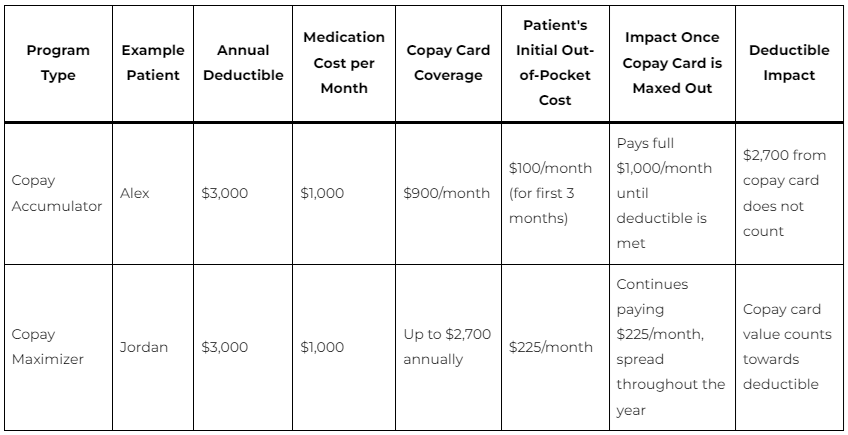

In a copay accumulator program, when a patient uses a drug manufacturer’s copay card or coupon to pay for a medication, this amount does not count towards their deductible or out-of-pocket maximum. Once the copay assistance is exhausted, the patient must pay out-of-pocket until their deductible is met.

Example:

Imagine a patient, Alex, has a $3,000 annual deductible. Alex uses a medication that costs $1,000 per month. Alex has a copay card from the drug manufacturer that covers $900 of the cost each month. For the first three months, Alex pays $100 out-of-pocket (the remaining cost after copay card), totaling $300. However, since the $2,700 paid by the copay card doesn’t count towards the deductible, Alex still has the full $3,000 deductible remaining. Once the copay card is maxed out, Alex must pay the full $1,000 per month until the deductible is met.

How Copay Maximizers Work

Copay maximizers set a minimum out-of-pocket cost for all patients using a manufacturer’s copay card, regardless of the actual drug cost. The program spreads the value of the copay card across the year, ensuring that it counts towards the deductible but also maximizing the time the patient uses the copay assistance.

Example:

Consider another patient, Jordan, with a similar $3,000 deductible. Jordan’s medication costs $1,000 per month, with a copay card covering up to $2,700 annually. Instead of using the $900 per month from the copay card, the insurer sets Jordan’s minimum monthly out-of-pocket cost at $225 ($2,700 / 12 months). This way, the copay card lasts the entire year, but Jordan consistently pays more each month. The payments go towards the deductible, but Jordan’s out-of-pocket costs are spread throughout the year.

Key Differences and Impacts

Accumulator programs can lead to a sudden, large out-of-pocket expense once the copay assistance runs out, while maximizer programs spread out costs but ensure higher consistent payments from the patient. Both strategies can lead to increased out-of-pocket costs for patients, especially those needing high-cost medications. They can also lead to confusion and financial strain, as patients may not fully understand how their payments are being applied towards their deductibles.

Conclusion

Copay accumulator programs represent a complex and contentious issue in healthcare. While PBMs and insurers may argue that these programs are necessary to control costs and ensure fair pricing, the direct impact on patients, particularly those requiring expensive treatments, is often negative. Increased costs can lead to medication non-adherence, potentially worsening health outcomes.

The role of PBMs in these programs, coupled with the lack of transparency and the push to get employer buy-in, highlights the need for greater scrutiny and regulatory intervention to protect patient interests. In summary, both copay accumulators and maximizers are cost-management strategies used by insurers and PBMs that can significantly alter the financial burden on patients, often leading to higher out-of-pocket expenses over time.