Do drug benefit managers reduce health costs?

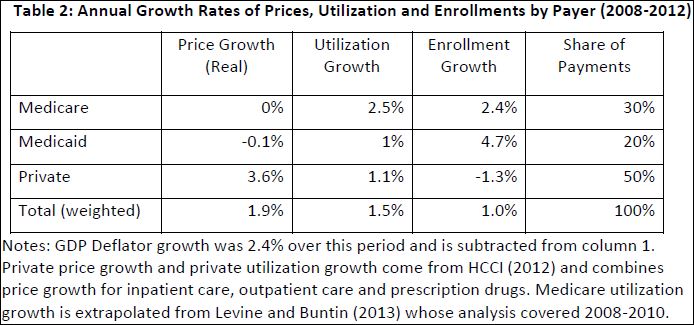

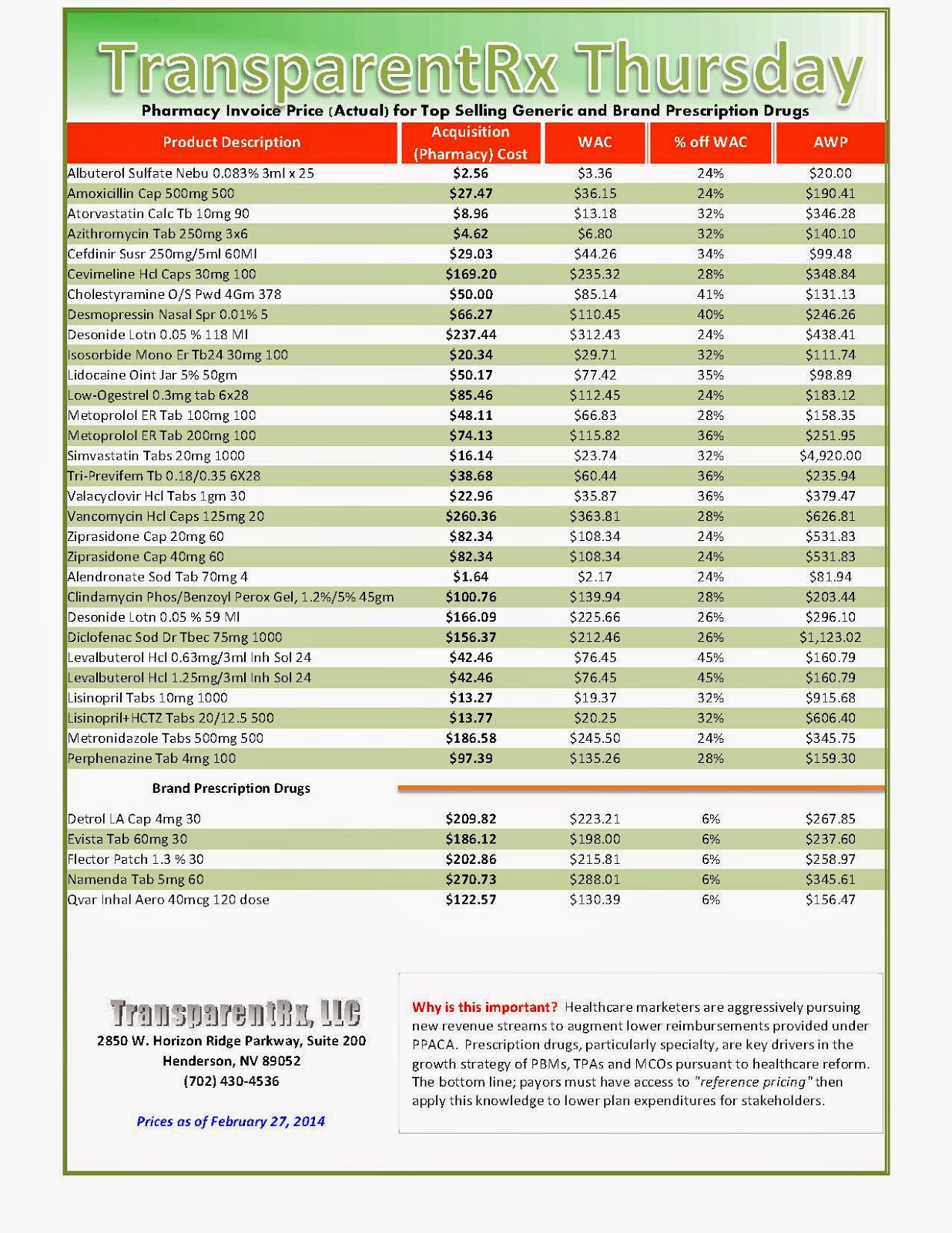

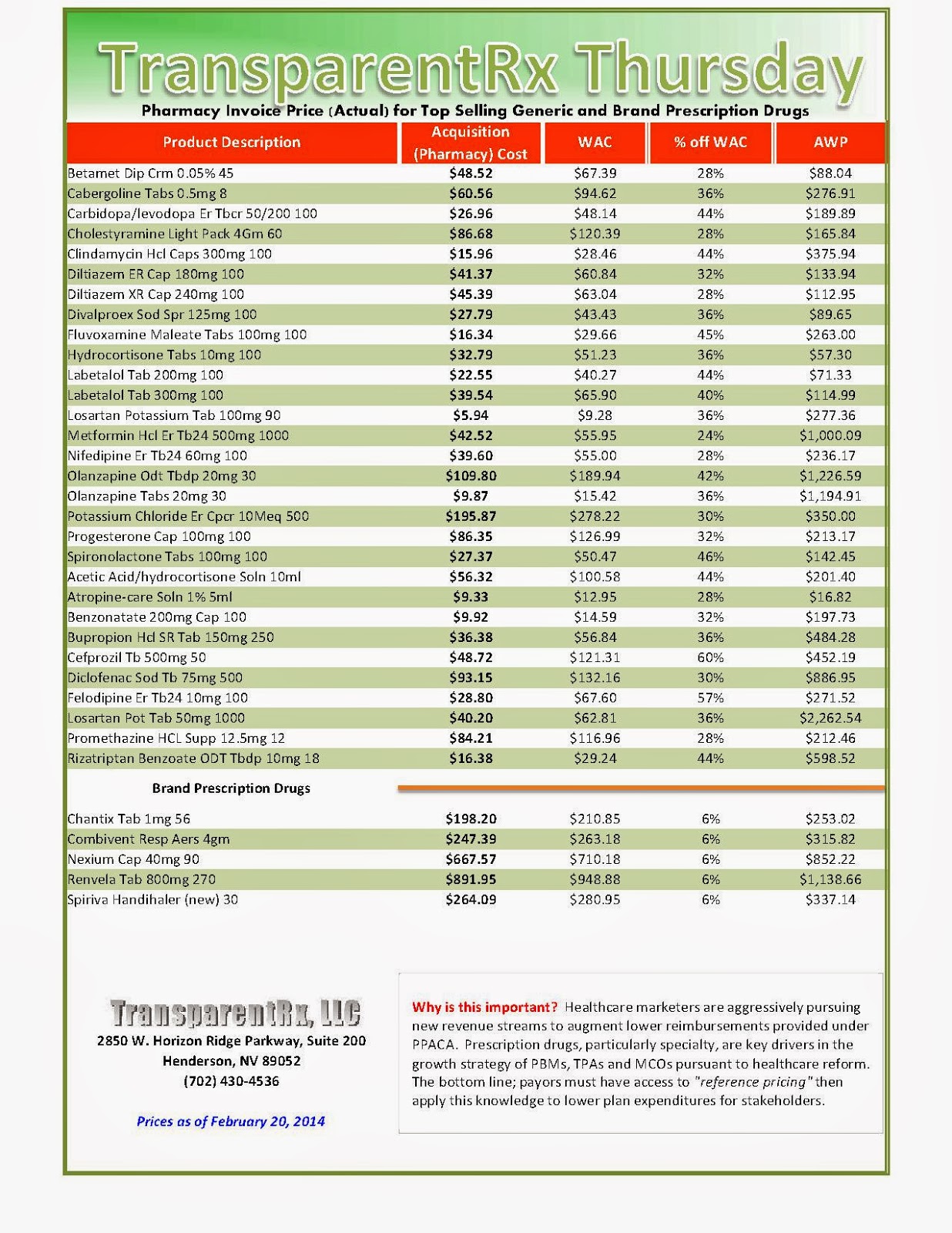

The roles of PBMs have expanded from simply handling prescription billing about 15 years ago to deciding which drugs insurers cover, what they cost and how much pharmacies are reimbursed for them.

Now some lawmakers are trying to rein them in. Legislation is pending in 14 states that would require more pricing disclosure by these companies, which process the drug benefits for virtually every American with insurance.

PBMs cut private deals with drug makers and then set maximum amounts they’ll reimburse drugstores for generic drugs and what they’ll charge companies, insurers or other clients for the drugs. The difference between these two numbers is often called “spread pricing,” and remains a murky but highly profitable area. To continue reading click here…

by Jayne O’Donnell, USA TODAY

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)