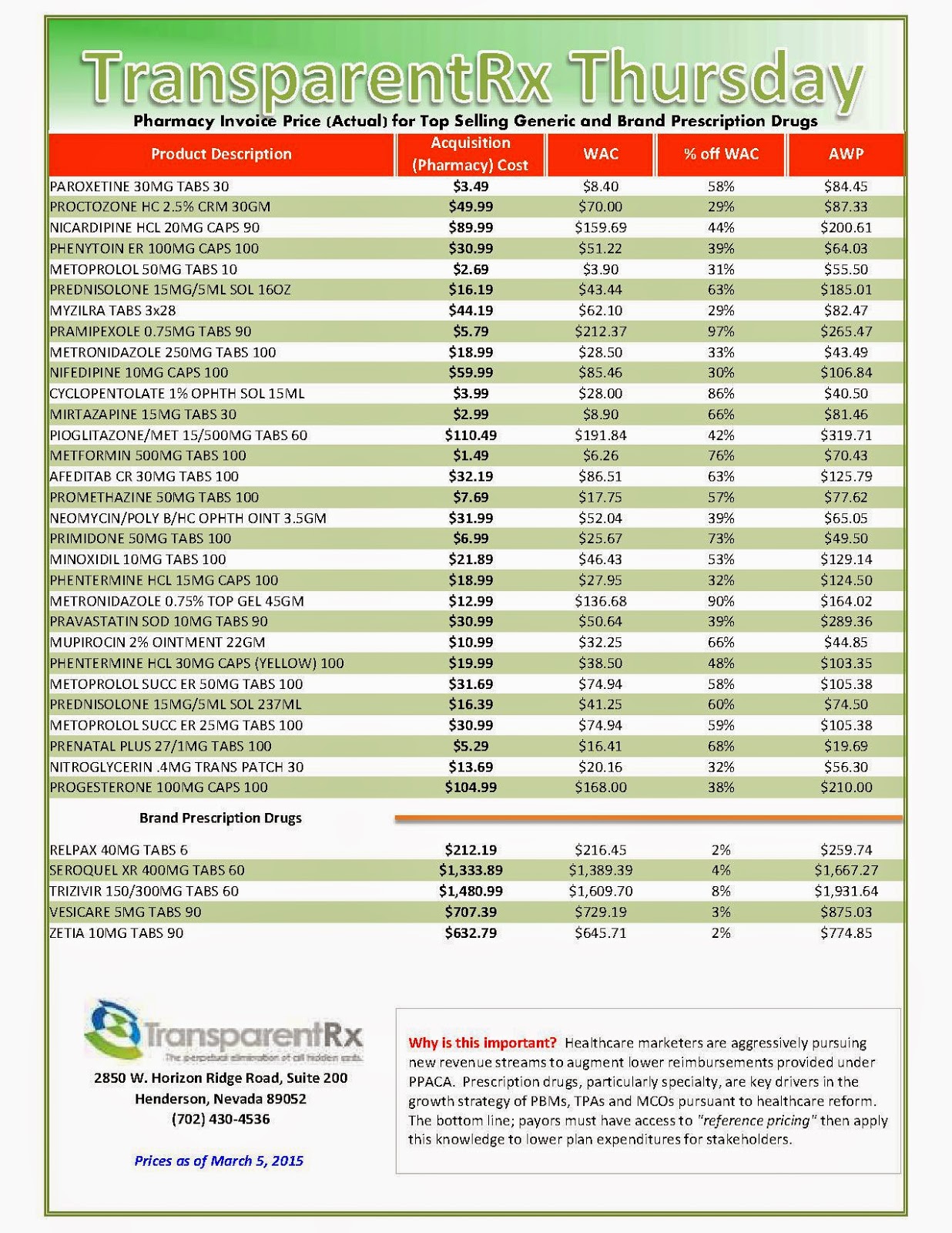

Reference Pricing: Pharmacy Invoice Cost (ACTUAL) for Top Selling Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs

The costs shared below are what our pharmacy actually pays; not AWP, MAC or WAC. The bottom line; payers must have access to “reference pricing.” Apply this knowledge to hold PBMs accountable and lower plan expenditures for stakeholders.

Step #1: Obtain a price list for generic prescription drugs from your broker, TPA, ASO or PBM every month.

Step #2: In addition, request an electronic copy of all your prescription transactions (claims) for the billing cycle which coincides with the date of your price list.

Step #3: Compare approximately 10 to 20 prescription claims against the price list to confirm contract agreement. It’s impractical to verify all claims, but 10 is a sample size large enough to extract some good assumptions.

Step #4: Now take it one step further. Check what your organization has paid, for prescription drugs, against our pharmacy cost then determine if a problem exists. When there is a 5% or more price differential (paid versus actual cost) we consider this a problem.

When better pricing is discovered the contract language should stipulate the client be indemnified. Do not allow the PBM to limit the market check language to a similar size client, benefit design and/or drug utilization. In this case, the market check language is effectually meaningless.

Do you want to eliminate overpayments to PBMs now? The fastest path to pharmacy benefits cost containment starts here.

The Makings of a Good Drug Formulary

- An open formulary is a list of recommended drugs. Under this structure, most drugs are reimbursed irrespective of formulary status. However, the client’s plan design may exclude certain drugs (e.g., OTC, cosmetic and lifestyle drugs). Physicians, pharmacists, and members are encouraged by PBMs via mailings, electronic messaging, and other means to prescribe and dispense formulary drugs.

- An incented formulary applies differential co-pays or other financial incentives to influence patients to use, pharmacists to dispense, and physicians to write prescriptions for formulary products.

- A closed formulary limits reimbursement to those drugs listed on the formulary. Non-formulary drugs are reimbursed if the drugs are determined to be medically necessary, and the member has received prior authorization.

In general, self-insured employers and insurance carriers outsource both administrative and clinical services to a PBM. Managed care organizations (MCOs) and some insurers may elect to retain formulary and clinical control, including manufacturer contracting, and outsource only administrative services such as claims processing and benefit administration to a PBM.

|

| Example of a tiered formulary (click to enlarge) |

Sources: PwC Study of Pharmaceutical Benefit Management

Reference Pricing: Pharmacy Invoice Cost (ACTUAL) for Top Selling Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs

The costs shared below are what our pharmacy actually pays; not AWP, MAC or WAC. The bottom line; payers must have access to “reference pricing.” Apply this knowledge to hold PBMs accountable and lower plan expenditures for stakeholders.

Step #1: Obtain a price list for generic prescription drugs from your broker, TPA, ASO or PBM every month.

Step #2: In addition, request an electronic copy of all your prescription transactions (claims) for the billing cycle which coincides with the date of your price list.

Step #3: Compare approximately 10 to 20 prescription claims against the price list to confirm contract agreement. It’s impractical to verify all claims, but 10 is a sample size large enough to extract some good assumptions.

Step #4: Now take it one step further. Check what your organization has paid, for prescription drugs, against our pharmacy cost then determine if a problem exists. When there is a 5% or more price differential (paid versus actual cost) we consider this a problem.

When better pricing is discovered the contract language should stipulate the client be indemnified. Do not allow the PBM to limit the market check language to a similar size client, benefit design and/or drug utilization. In this case, the market check language is effectually meaningless.

Click here to register: “How To Slash the Cost of Your PBM Service, up to 50%, Without Changing Providers or Employee Benefit Levels.” [Free Webinar]

Mild to aggressive; remedies for reducing prescription drug prices

But since drug ads provide a major revenue source for media outlets, mass journalism largely failed to treat the matter as a major, persistent social problem. Instead, the stories about trips to Canada and rent-versus-drugs usually lacked useful context, instead appearing as quaint pieces of human interest or as quizzical parts of the passing fanfare.

Recently the media have been running stories where health care analysts, physicians, administrators at provider networks and other observers eagerly discuss their respective ideas for curtailing drug prices. Four recent approaches to the matter deserve some attention.

The first was prompted by last week’s announcement from Britain’s National Health Service that the number of therapies its Cancer Drug Fund covers would be cut by 30% to contain unsustainable costs.

|

| Graphic by Bloomberg Business Week |

Cancer drugs stand in the front line of soaring drug prices. As the United Nations predicts the number of people worldwide over age 65 will triple between 2010 and 2050, the older population will spike the incidence of age-related diseases such as cancer. The WHO predicts a 70% increase in the number of cancer cases during the next 20 years. Global spending on cancer drugs already has more than doubled in the past decade, according to IMS, a pharma data collector.

This led pharma consultant Bernard Munos to tell the Financial Times that “the cost of these drugs is not sustainable…[and] what is happening in the UK today will happen in America tomorrow.” Mr. Munos claims the best answer lies in ending Big Pharma R&D and outsourcing the function to smaller, nimbler biotechs and startups with lower expense levels.

That sounds reasonable but it is unlikely to contain spiraling drug costs. Big Pharmas are already moving in that direction by buying biotechs or making deals to subsidize research at the smaller companies. The entire thrust of research across the range of specialty products in areas such as oncology, auto-immune diseases, and virology already involves research by university medical centers and small biotechs.

Munos’s suggestion fails entirely to get at the heart of the matter. As leukemia specialist Hagop Kantarjian, at Houston’s MD Anderson Cancer Center, told the Financial Times, “no amount of innovation can justify the doubling in average US prices over the past decade to more than $100,000. ‘It is profiteering and greed,’ he says.”

A second line of analysis proceeds by ignoring growing drug costs and, instead, recommends giving everyone a vastly more generous prescription drug plan.

This month, in the American Journal of Public Health, researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston published their analysis of more than a score of studies that appeared between 1990 and 2013. They found that better insurance for prescription drugs could help reduce total health care costs by lowering the levels of sickness and death.

The authors point out that although more generous benefits would create some higher initial costs, they claim the reductions in “preventable patient morbidity and mortality” would more than offset those costs.

Although less sickness and death do represent the goals of health care, the fact is that obtaining such desirable outcomes without controlling drug costs would provide pharma with a blank check to gouge every public and private payer.

Funding for the generous prescription plans recommended by the authors would have to come from somewhere and, ultimately, that means the American consumer and taxpayer would foot the bill to enrich pharma. By failing to give drug cost control equal consideration with coverage enhancement, the authors relegate their study to the category of blue sky irrelevance.

As long as drug companies can pay their pharmaco-economic analysts to make the case that a drug’s total of direct, indirect and implied costs reduce higher spending somewhere down the line, pharma will abuse the results. They will try pushing expensive products intended for a select number of patients on the vast majority. The emerging class for LDL cholesterol, PCSK-9’s, represent a clear example of that.

Once pharma launches its PCSK-9 inhhibitors, the industry’s flacks among medical opinion leaders will scare up business for their sponsors and grants for themselves under the-lower-the-better banner by recommending the new class for everyone, not just the familial homozygous. Pretty soon, a $1,000 a pill will seem cheap.

But other analysts offer a bit more hope for controlling drug prices. In last week’s New York Times, Dr. Peter Bach, a physician and the director of Memorial Sloan Kettering’s Center for Health Policy and Outcomes in New York, moved a step beyond a blank check for the drug companies.

Dr. Bach essentially recommended that public payers such as Medicare and Medicaid manage their drug formularies similarly to the way Express Scrips, the largest pharmacy benefit manager for private payers, has started to do.

According to Dr. Bach, the law requiring public payers to cover all approved drug products permits pharma to maintain its pricing cartel, rather than obliging brands in the same category to compete on price. By competing for reimbursable status on restrictive drug formularies that cover a limited number of medications, drug companies would have to offer optimal cost-effectiveness.

A third, fourth or fifth competitor in a class wouldn’t get covered by a prescription plan if it offers comparable effectiveness at a similar cost to what’s already available. Lacking a substantially better clinical profile, a company would have to compete on price to get its product covered.

According to Dr. Bach, the mere threat by European countries to deny reimbursement contributes significantly to the fact that their drug prices are half as much as what the U.S. pays.

If the action holds and isn’t reversed by the country’s business-fawning prime minister, it will mean generics companies there such as Natco will be able to sell the medication for $1 a pill instead of the $1,000 that Gilead extorts from U.S. payers. Leena Menghaney from Doctors Without Borders praised the effort to deny Sovaldi a patent, claiming it would allow open market competition in India.

Now here Dr. Bach’s observation holds true in that just the threat of compulsory licensing, exercised only rarely, can be enough to curb pharma’s unmitigated greed. That enables a range of remedies for controlling drug prices, from mild and regular to harsh and infrequent.

Alas, the successful containment of drug costs, whether through these or other means, demands an aggressive vigilance and some public empathy on the part of politicians and payers. Unfortunately, it remains unlikely that the majority in Congress, in thrall to the moneyed interests of pharma and major hospital networks, possess any public empathy outside their duck dynasty and C-suite constituencies.

Health insurers, for their part, remain too contented paying enormous compensations to their senior executives while costs for the middle class continue to grow. Meantime, as health care costs expand the sector from its current 18% of GDP to 20% and beyond, no safeguard exists for preventing pharma from jeopardizing the very qualities their products are supposed to improve — the length and quality of life.

Written by Daniel R. Hoffman, Ph.D.,

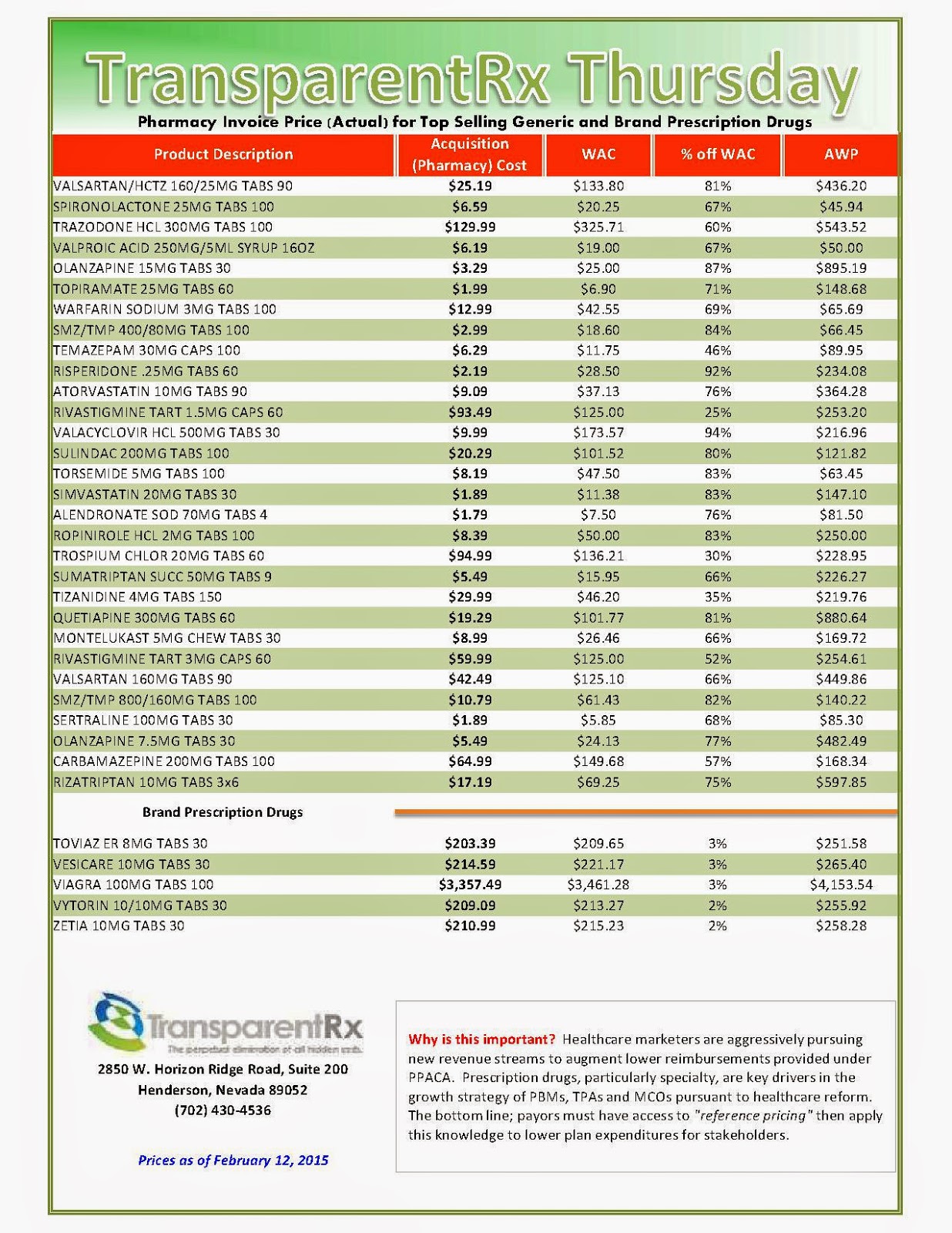

Reference Pricing: Pharmacy Invoice Cost (ACTUAL) for Top Selling Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs

The costs shared below are what our pharmacy actually pays; not AWP, MAC or WAC. The bottom line; payers must have access to “reference pricing.” Apply this knowledge to hold PBMs accountable and lower plan expenditures for stakeholders.

Step #1: Obtain a price list for generic prescription drugs from your broker, TPA, ASO or PBM every month.

Step #2: In addition, request an electronic copy of all your prescription transactions (claims) for the billing cycle which coincides with the date of your price list.

Step #3: Compare approximately 10 to 20 prescription claims against the price list to confirm contract agreement. It’s impractical to verify all claims, but 10 is a sample size large enough to extract some good assumptions.

Step #4: Now take it one step further. Check what your organization has paid, for prescription drugs, against our pharmacy cost then determine if a problem exists. When there is a 5% or more price differential (paid versus actual cost) we consider this a problem.

When better pricing is discovered the contract language should stipulate the client be indemnified. Do not allow the PBM to limit the market check language to a similar size client, benefit design and/or drug utilization. In this case, the market check language is effectually meaningless.

Click here to register: “How To Slash the Cost of Your PBM Service, up to 50%, Without Changing Providers or Employee Benefit Levels.” [Free Webinar]

Specialty Pharmacy: The Top 10 Trends Payers Should Be Following

|

| CVS Caremark 2013 Drug Trend Report |

9. Specialty Distribution Networks Are Expanding To Allow for Greater Access And Control of Specialty Drugs

8. Biosimilars Are Coming; The First Is Poised For FDA Approval

7. Health Care, As A Whole, Is Evolving Into A Pay-For-Performance Marketplace

6. Growing Adaptation Of Data Analytics Will Improve Patient Outcomes

5. Poor Patients Continue To Flood The Specialty Space Through PPACA

4. As Drug Costs Go Up, Adherence Goes Down Thus Hospital Spend Increases

3. The Marriage Of PBMs And Specialty Pharmacy Continues To Strengthen

2. Specialty Drug Manufacturers Continue To Limit Distributors For Margin Protection

1. Cost Will Be Weighed Against The Outcome Not Hyperbole

Reference Pricing: Pharmacy Invoice Cost (ACTUAL) for Top Selling Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs

The costs shared below are what our pharmacy actually pays; not AWP, MAC or WAC. The bottom line; payers must have access to “reference pricing.” Apply this knowledge to hold PBMs accountable and lower plan expenditures for stakeholders.

Step #1: Obtain a price list for generic prescription drugs from your broker, TPA, ASO or PBM every month.

Step #2: In addition, request an electronic copy of all your prescription transactions (claims) for the billing cycle which coincides with the date of your price list.

Step #3: Compare approximately 10 to 20 prescription claims against the price list to confirm contract agreement. It’s impractical to verify all claims, but 10 is a sample size large enough to extract some good assumptions.

Step #4: Now take it one step further. Check what your organization has paid, for prescription drugs, against our pharmacy cost then determine if a problem exists. When there is a 5% or more price differential (paid versus actual cost) we consider this a problem.

When better pricing is discovered the contract language should stipulate the client be indemnified. Do not allow the PBM to limit the market check language to a similar size client, benefit design and/or drug utilization. In this case, the market check language is effectually meaningless.

Click here to register: “How To Slash the Cost of Your PBM Service, up to 50%, Without Changing Providers or Employee Benefit Levels.” [Free Webinar]

Generic drug price hikes hit pharmacists and payers

“Sticker shock” may be the best term to describe the malady that is hitting independent pharmacists.

They arrive at work – mostly behind the prescription counters at small drugstores – and, when they turn on their computers, are shocked by sudden and drastic price increases for generic medicines.

In November, one pharmaceutical vendor increased the price of a tube of prescription cream to treat athlete’s foot by more than 800 percent. In April, the price of one generic antibiotic went from about 15 cents a capsule to more than $2.70 a capsule, an increase of more than 1,700 percent.

“It is like a surprise, every day,” said Doug Hess, a pharmacist who owns Doug’s Family Pharmacy in Caernarvon Township. Brandon Wiley, who is head pharmacist and manager at Wiley’s Pharmacy in East Hempfield Township, Lancaster County, said he once paid $20 or $30 for 500-tablet bottles of the antibiotic, Doxycycline, that he would use to fill many prescriptions. “Now, it is over $1,000 for the same bottle,” he said.

A lot of people buying prescriptions don’t feel the financial hit – at least not immediately – because their prescription insurance plans require only a co-pay. But Robert Frankil, who lives in Montgomery County and owns an independent pharmacy in Bucks County, said the complex and confusing financial relationships that cloud the connection between drugmakers and drug consumers – involving vastly profitable companies called “pharmacy benefits managers” – affect the public at large.

Frankil went to Washington in November to testify before a U.S. Senate hearing on the spikes in generic drug prices. “Eventually, there is a trickle down to everyone,” he said in an interview. “When you look at the rate of drug increases in price compared to the rate of inflation, it is ridiculous.”

After the hearing, Sen. Bernie Sanders, a Vermont independent, issued a statement that said drug companies have seen an opportunity to make a lot of money and have seized the opportunity.

“There is greed at work in the pharmaceutical industry,” Sanders said. He and Rep. Elijah Cummings, D-Md., have introduced legislation that would require drug companies to reimburse Medicaid if they raise the prices of generic drugs more quickly than the rate of inflation.

A spokesman for the Washington-based Generic Pharmaceutical Association, a trade group, responded to questions by referring to statements issued in November by association President and CEO Ralph G. Neas.

“This legislation once again misses the forest for the trees,” Neas said, referring to the Sanders-Cummings initiative. “In actuality, generic drugs continue to be a resounding success in lowering health care costs and benefiting patients. Indeed, generics saved $239 billion in 2013 – a 14 percent increase in savings from 2012 – and more than $1.46 trillion over the recent decade.”

Neas cited a report from Express Scripts, the largest pharmacy benefits management company, that showed that since 2008, the price of brand drugs has almost doubled, but the price of generic drugs has been cut roughly in half. Regardless, John Norton, a spokesman for the Virginia-based National Community Pharmacists Association, said the price spikes cannot be a good thing.

“If you are having huge and relatively random price increases you are going to have problems,” Norton said. Independent pharmacists have their own point of contention with so-called “PBM” companies.

When a manufacturer suddenly increases the cost of a generic drug, the PBM sometimes does not boost its reimbursement payment to match the new price for several months, they said. That means the independent pharmacy must swallow the price difference for a time.

“We are selling the drug at a loss until the increase,” Wiley said. Express Scripts Holding Company’s stock, traded on NASDAQ, has doubled in price in the past three years. Lawmakers in Harrisburg also have heard testimony concerning drug prices. In 2013, at a state House committee hearing on proposed pharmacy benefit management legislation, Express Scripts spokesman Dave Dederichs said the company’s use of PBM “tools” has helped slow the increase in costs of prescription drugs.

“We are here today in opposition to the draft PBM legislation, which will act as a hindrance on the aforementioned tools to lower prescription drug costs for both plan sponsors and consumers,” Dederichs said in submitted testimony. Such statements fly in the face of what independent pharmacists frequently see.

Eric Esterbrook, owner of Esterbrook Pharmacy in West Reading, recalled the morning he came to work and was told by staffers that the price of Doxycycline had skyrocketed. “We were all just dumbfounded,” Esterbrook said. “It was just shocking.”

by | Ford Turner

Reference Pricing: Pharmacy Invoice Cost (ACTUAL) for Top Selling Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs

The costs shared below are what our pharmacy actually pays; not AWP, MAC or WAC. The bottom line; payers must have access to “reference pricing.” Apply this knowledge to hold PBMs accountable and lower plan expenditures for stakeholders.

Step #1: Obtain a price list for generic prescription drugs from your broker, TPA, ASO or PBM every month.

Step #2: In addition, request an electronic copy of all your prescription transactions (claims) for the billing cycle which coincides with the date of your price list.

Step #3: Compare approximately 10 to 20 prescription claims against the price list to confirm contract agreement. It’s impractical to verify all claims, but 10 is a sample size large enough to extract some good assumptions.

Step #4: Now take it one step further. Check what your organization has paid, for prescription drugs, against our pharmacy cost then determine if a problem exists. When there is a 5% or more price differential (paid versus actual cost) we consider this a problem.

When better pricing is discovered the contract language should stipulate the client be indemnified. Do not allow the PBM to limit the market check language to a similar size client, benefit design and/or drug utilization. In this case, the market check language is effectually meaningless.

Click here to register: “How To Slash the Cost of Your PBM Service, up to 50%, Without Changing Providers or Employee Benefit Levels.” [Free Webinar]

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)