Three Reasons Why the PBM Transparency Act Won’t Reduce Drug Costs

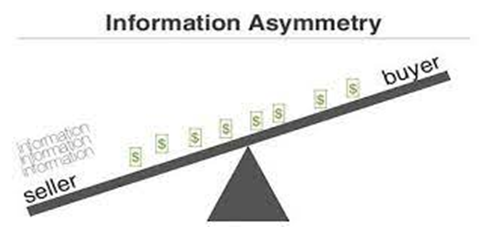

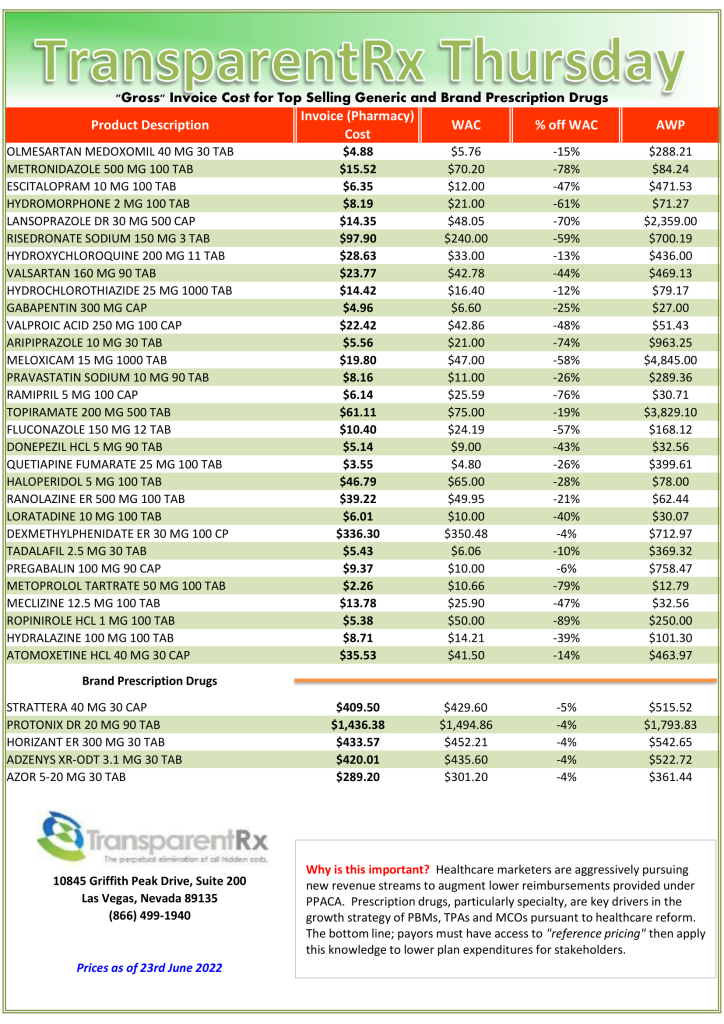

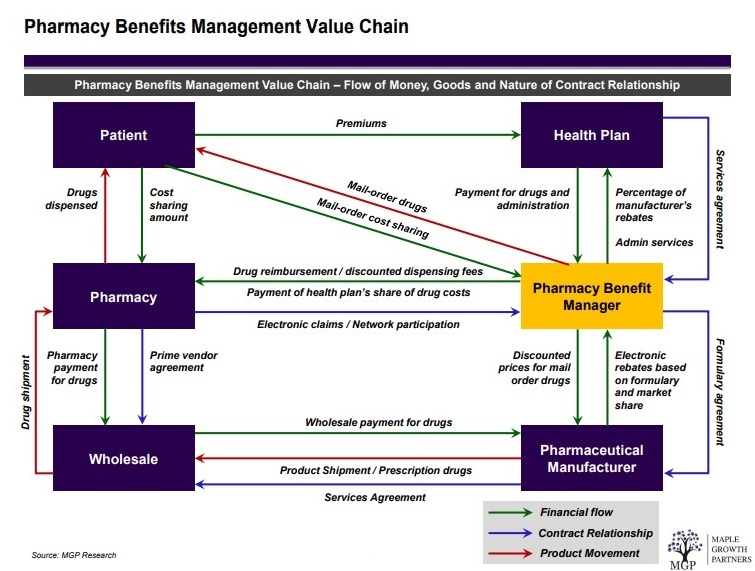

A pharmacy benefit manager’s (or PBM) essential job ought to be uncomplicated: act in the best interest of patients and clients while delivering lowest net cost. Instead, non-fiduciary PBMs are leveraging information failure to their financial advantage. Information failure or Asymmetric Information is a type of market failure where individuals or firms have a lack of information about economic decisions[i].

The Pharmacy Benefit Manager Transparency Act of 2022 was introduced by Senate Commerce Science, and Transportation Committee and Senate Judiciary Committee to shine a light on the Pharmacy Benefit Manager market and empower the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and state attorneys general to stop unfair and deceptive PBM business practices. I propose three reasons why the PBM Transparency Act won’t reduce drug Costs.

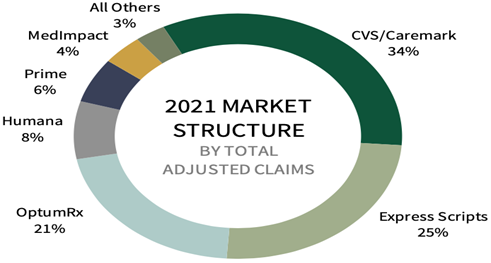

- Non-Fiduciary PBMs are Protecting Rebate Spreads by Creating Group Purchasing Organizations (“GPOs”). For example, a report[ii] by Nephron research says, “contracting entities are shifting discounts from the rebate profit pool 99% of which flows to clients to fee pools that may be retained by the PBM. In other words, non-fiduciary PBMs have shifted their management fee to GMFs or group purchasing organization management fees. They’ve also shielded themselves from spread pricing revenue loss by powering discount cards.

- Non-Fiduciary PBMs are Protecting Ingredient Cost Spreads by Sharing Pharmacy Network Access. One initiative, called Inside Rx, offers discounts on brand name drugs to a select group of consumers typically those under age 65, aren’t on government insurance programs such as Medicaid or Medicare, or are under or uninsured. Through a collaboration that comprises drug companies, Express Script’s pharmacy network, and tech partner GoodRx, the program is designed to make drugs affordable for patients with high-deductible insurance plans, or no insurance at all. The truth is that it is a huge revenue source and in some cases the margins are larger than core PBM services.

- Non-Fiduciary PBMs are Protecting Overall Gross Margins Leveraging 100% Markups on Medical Benefit Drug Claims. It’s no secret prescription drugs cost more under the medical benefit then they do under the pharmacy benefit. In the turf war between hospitals and health insurers over physician practices, hospitals are winning by a long shot. But they’d be ill advised to get too comfortable. A slew of recent activity shows that insurers are clawing their way back, whether by outright purchases of medical practices or targeting outpatient facilities that employ doctors. UnitedHealth Group has long led the charge to buy medical practices, absorbing several a year into its OptumCare subsidiary. National insurer Humana and, most recently, Anthem have also gotten into the game. Each of these two national insurers also maintains ownership in a pharmacy benefit manager.

Conclusion – Three Reasons Why the PBM Transparency Act Won’t Reduce Drug Costs

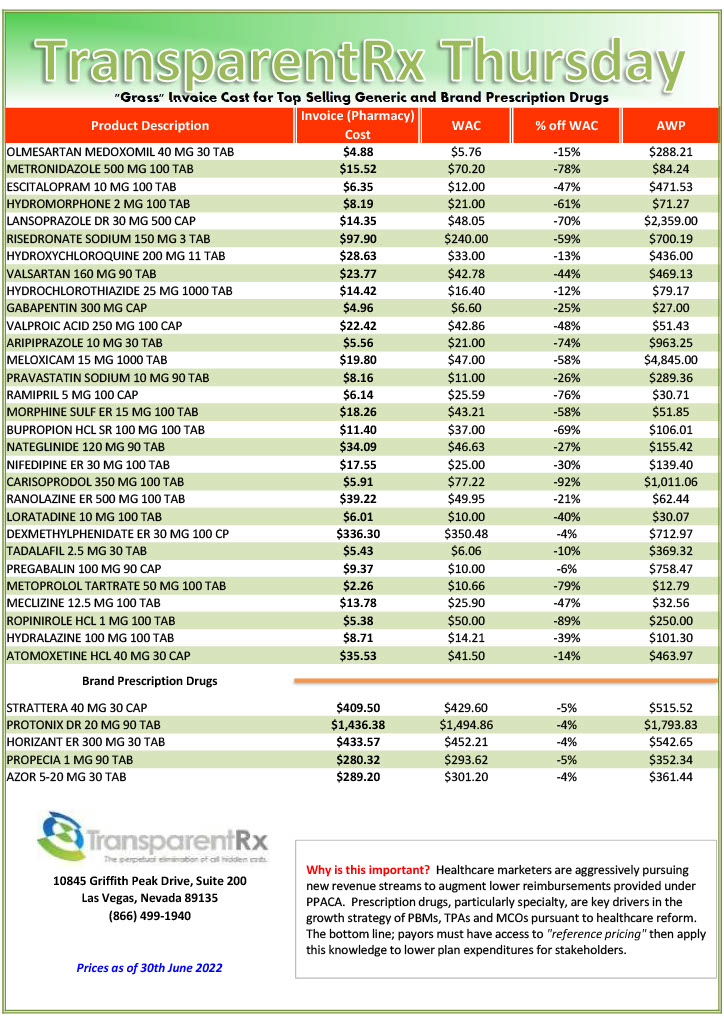

John F. Kennedy said, “The greater our knowledge increases the more our ignorance unfolds.” Most self-insured employers, and their advisers, don’t know what they don’t know. Pharmacy Benefit Managers provide transparency and disclosure to a level demanded by the competitive market and generally rely on the demands of prospective clients for disclosure in negotiating their contracts. The best proponent of transparency is informed and sophisticated purchasers of PBM services.

[i] Pettinger, 2022, “Information Failure”, Economics Help: Helping to Simplify Economics, https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/glossary/information-failure/

[ii] Argentieri, 2022, “Self-funding pharmacy benefits: What organizations need to consider”, The Business Journals, https://www.bizjournals.com/buffalo/news/2022/06/06/self-funding-pharmacy-benefits-what-organizations.html