The List of PBM Formulary Exclusions Grew in 2023 [Weekly Roundup]

The List of PBM Formulary Exclusions Grew in 2023 and other notes from around the interweb:

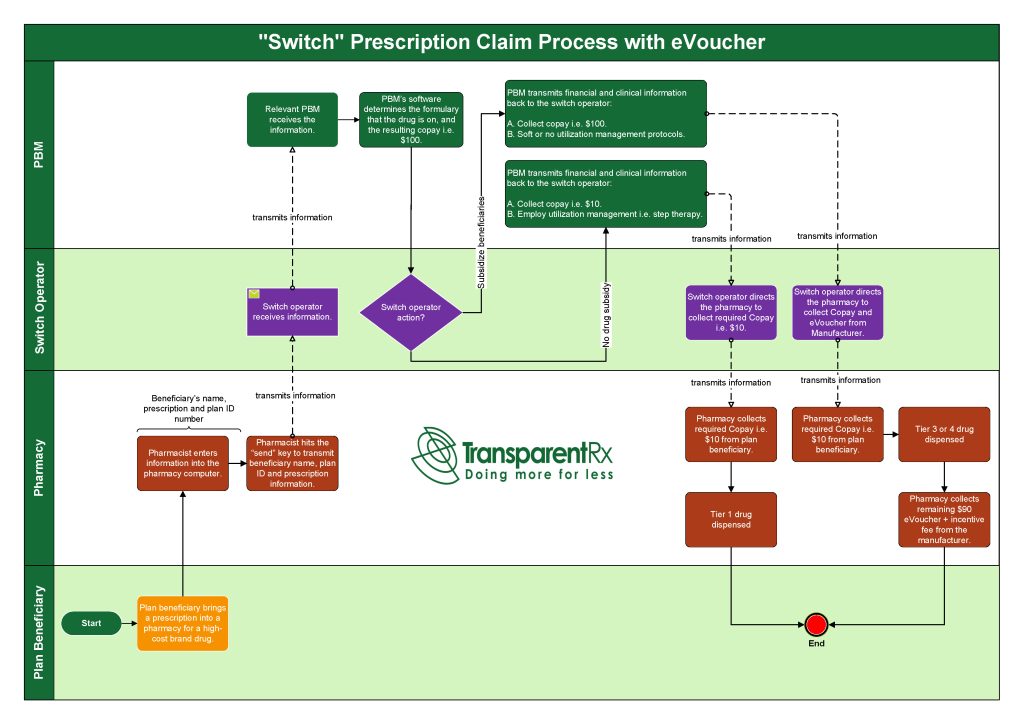

- The List of PBM Formulary Exclusions Grew in 2023. Several of the omitted products can be cheaper list-priced generics or biosimilars that the PBMs ignore in favor of branded pharmaceuticals. Critics of the practice claim that brand manufacturers’ rebates are frequently to fault for this behavior, even though patients may be saddled with increased copays. Formulary exclusions were first used by major PBMs in 2011. The white bagging practice, in which payers decline to cover physician-administered pharmaceuticals unless they are delivered (white bagged) to the physicians by an authorized pharmacy, has contributed to the spread of the exclusions from the pharmacy benefit to the medical benefit side. A lot of states are taking legislative action to control white bagging. Plans can no longer refuse to pay suppliers for providing medications given by clinicians in Louisiana. Moreover, insurers are required to cover medical and pharmaceutical benefit pathways under Arkansas’ anti-white bagging rule, which only pertains to hematology and oncology. The preferred pathway is up to the patient and the physician.

- Federal Judge Rules Cheaper Drugs Can Be Imported From Canada. In a setback to the pharmaceutical industry, a federal judge has tossed a lawsuit that sought to prevent state governments from importing medicines from Canada. And the decision is likely to embolden more states to now consider the approach as they look to lower the cost of prescription drugs. The 26-page ruling noted that to have standing, plaintiffs must prove that they have suffered an “injury in fact,” that the injury is traceable to the defendants’ conduct, and that the injury is likely to be remedied by a favorable decision. And in two distinct aspects, the plaintiffs had no standing to bring the case against the federal agencies, Kelly ruled. The DC Circuit Court has struck a blow against the pharmaceutical lobbying group PhRMA and other plaintiffs’ attempt to stop states from importing drugs from Canada. Joined alongside public health group Partnership for Safe Medicines and advocacy group Council for Affordable Health Coverage, PhRMA was rebuffed by Judge Timothy Kelly, who dismissed the civil suit due to a lack of standing.

- California Gov. Gavin Newsom ends $54 million Walgreens contract over abortion pill dispute. Mifepristone is a pill that when combined with another pill will end a pregnancy. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the pill in 2000 for use in up to the 10th week of pregnancy. Today, more than half of all abortions in the U.S. are done by pills, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a research group that supports abortion rights. After the U.S. Supreme Court last year overturned the federal right to an abortion, more than a dozen states have restricted the use of abortion pills. But those restrictions are being challenged in court. Attorneys general in twenty states, mostly with Republican governors, have warned Walgreens and CVS they could face legal consequences if they sell abortion pills in their states. Last week, Walgreens confirmed it sent a response to each attorney general saying it would not dispense the drug in their states. Newsom responded to that news on Monday, posting in a message on Twitter that California won’t be doing business with Walgreens “or any company that cowers to the extremists and puts women’s lives at risk.”

- Top Threats, Priorities in Employer-Sponsored Health Plan Benefits. Employers shared the main threats and priorities that they encounter as they try to manage employer-sponsored health plan benefits, according to a survey from the Midwest Business Group on Health (MBGH). The organization surveyed almost 60 large, self-insured employers from a broad span of industries. The survey was conducted in 2022. The top three threats to employer-sponsored healthcare coverage according to employer respondents were: high-cost pharmacy claims (94 percent), medical inflation (91 percent), and extremely expensive therapies with Food and Drug Administration approval (91 percent). Other obstacles included expensive medical claims, specialty drug spending, and high-cost patient populations. In response to these and other threats, employers highlighted certain priorities, from managing pharmacy costs to bolstering mental healthcare services. Nearly all the employers indicated that engagement in programs and benefits was a key priority for their health benefits strategies (96 percent) as well as communication around health benefits (94 percent). Over 90 percent of employers also mentioned that financial wellness, mental health, well-being, chronic disease management, preventive care services, and specialty drug management were also priorities. Most employers also agreed that diversity, equity and inclusion and the culture around health in their companies were priorities.