In less than two decades, transparent third-party prescription claims adjudication has evolved into the extremely profitable and opaque pharmacy benefit management industry of today. PBMs make most of the value decisions that plan sponsors are unqualified for or choose not to make. This wouldn’t be a problem except for the fact that most PBMs are non-fiduciary, which means their interests are not aligned to those of their clients.

Worse yet, non-fiduciary PBMs leverage the purchasing power of unsophisticated plan sponsors by negotiating with drugmakers and pharmacies for their financial benefit. Before non-fiduciary PBMs learned they could leverage the purchasing power of unsophisticated purchasers for their own financial gain, they focused on cost-efficiency or getting the best outcomes for the lowest cost. In many cases, the focus has shifted to promoting the products that are most profitable to the PBM.

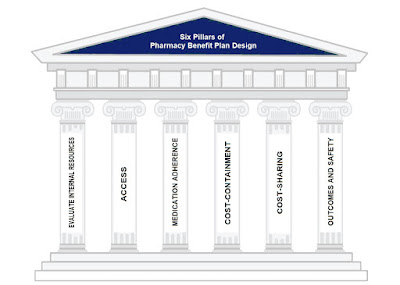

Smart purchasers of PBM services want more control over their plan design not less. If this is you, here are six pillars upon which to design your pharmacy benefit plan.

I. Evaluate your internal resources and pharmacy expertise

If you’re reading this and work for a self-funded employer never retain the services of a PBM or a PBM consultant who benefits when your pharmacy costs increase. Should you do so, never leave them completely to their own accord.

- Do you have the expertise within your company to design the pharmacy benefit plan? Or do you need pharmacy benefits education or the services of a pharmacy benefits consultant?

- How do you want to be involved in the management of the plan design after it is set up?

- Do you have the expertise and resources to manage the plan design or do you need to build in the incentives for the PBM to manage your program?

In other words, hire consultants not because you lack the requisite knowledge to design or manage the pharmacy benefit plan in-house, but because you lack the time or human capital to go it alone. Plan sponsors might be surprised to learn that many so called advisers know little more than they do when it comes to pharmacy benefits. Who is watching the watcher?

II. Access

A formulary is a list of medications for which a plan will provide reimbursement. When considering a formulary, access defines the basic aspects of a pharmacy benefit design which includes but is not limited to:

- The products that will be covered

- The products that will not be covered

- The products that need prior approval

- Plan cap or maximum dollar amount a plan will pay for outpatient drug benefits

- Mail service benefits including specialty pharmacy, if any

- Pharmacy network makeup

Managing a formulary and improving its efficiency involves an ongoing assessment of the drugs on the formulary as well as any new potential drug therapy treatments. Again, do not leave this responsibility solely in the hands of the PBM unless it has agreed to accept fiduciary responsibility. Lastly, plan design considerations must take into account DAW or dispense as written laws for each state.

III. Medication Adherence

Medication adherence is a large and growing issue that has an impact not only on patients’ health, but also on employer finances. Non-adherence to medications has been linked to 30-50% of treatment failures and 125,000 deaths each year, according to

statistics gathered by the American College of Preventive Medicine.

|

Figure 1. Gap Between a Written Prescription and Actual Medication Use

[Source: National Association of Chain Drug Stores, Pharmacies: Improving Health, Reducing Costs, July 2010. Based on IMS Health data] |

In addition, non-adherence results in $290 billion in annual healthcare spending, $100 billion of which is due to hospitalization and rehospitalization that could have been avoided if medications were taken as prescribed. Simply put, even the most perfectly designed plan in the world can’t make up for poor adherence. Monitor adherence plan-wide and take corrective action for patients whose adherence is average or worse.

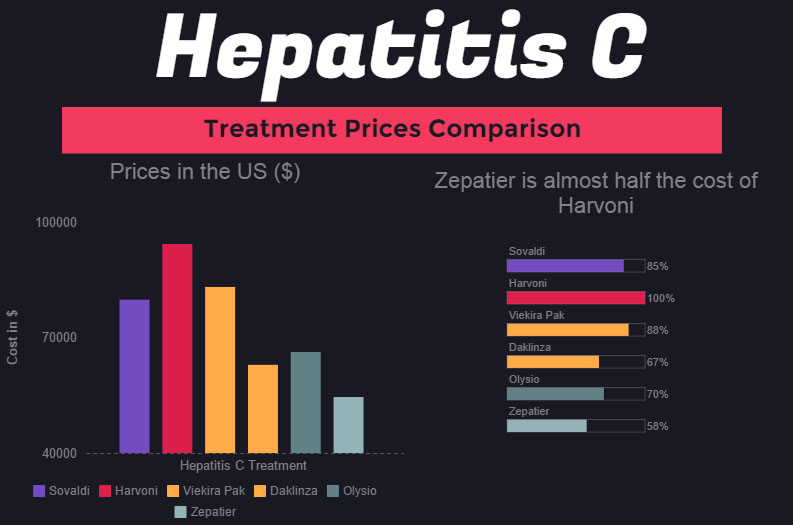

IV. Cost-Containment

Major cost-containment elements of pharmacy benefit plan design are plan restrictions, limitations and exclusions. There are many types of limitations used in varying degrees but they often lack the oversight [human] necessary to be effective over the long-haul. These elements encourage members to utilize low(er) cost alternatives:

- Therapeutic Substitution

- Mandatory Generic

- Plans caps or the maximum amount a plan will pay for outpatient drug benefits

- Partial fill programs or quantity limits on medication members can receive

- Step Therapy

V. Cost-Sharing

Refers to the members out of pocket cost. There are three major types of cost-sharing: copayments, deductibles and coinsurance.

- When members receive a more costly alternative to a preferred product they are required to pay the higher copayment

- When members receive a branded product which has an available generic equivalent, they are required to pay the additional costs associated with the branded

|

| Source: Milliman Commerical Specialty Medication Research: 2016 Benchmark Projections | |

According to the economic principles of demand, as price increases, demand tends to decrease. In the case of prescription drugs, price is the member’s OOP (out-of-pocket). As cost sharing increases, utilization decreases. However, it’s a catch twenty-two as there is a point of diminishing returns. You don’t want utilization to decrease so much that it causes an increase in hospitalizations or emergency room visits, for example.

VI. Outcomes and Safety

The sixth and final pillar does not provide or limits coverage for those products that do not improve or maintain the health of the members or have a tendency to be abused or overused. Some examples include:

- Hair growth treatments

- Over-the-counter drugs

- Growth hormones

- Erectile dysfunction

- Weight loss/gain drugs

- Smoking cessation products.

- Opioids

This portion of the pharmacy benefit design is accomplished by clearly defining which drugs and/or therapeutic categories will not be covered or are limited in their coverage.

Once a plan is in place there must be ongoing evaluation (far beyond standard reports) to determine how well the plan is achieving the goals and objectives upon which the plan is based. Critical to the process is the availability of data. I’m aware how tough some PBMs make it to get access to data. You would be wise to negotiate unrestricted access to this data upfront; before the contract is signed.