When the announcement was made last year that Marriott International was purchasing Starwood Hotels and Resorts I was ecstatic. This meant I would have access to more hotel properties, especially internationally, and let’s be honest the Starwood properties are just better. The Starwood hotels, at least in my experience, are more up to date and offer superior customer service.

The cynic in me, however, said this is going to be a tricky project [merging the two rewards programs] so I immediately set out to take screen shots of my accounts such as stays, points, and membership levels. One can never be too careful in protecting what they’ve earned in the digital age. Long story short these screenshots came in handy not too soon after the integration was complete.

On August 18, 2018 the Marriott and Starwoods Preferred Guest rewards programs were finally combined sort of. While the integration of the two programs was taking place in the background, I was learning how the SPG (starwoods preferred guest) program worked. During my research, what I learned shocked me!

First, Marriott platinum premier members are entitled to 10 complimentary suite upgrades every year. I’ve been a member for 15 years and never knew about this benefit! I’m not that picky but when on vacation I like to splurge. That’s a lie. I’m extremely picky when it comes to certain things like spending $300 or more of my hard earned money on a hotel room.

Second, Marriott platinum premier members are eligible for free suite upgrades at the Ritz Carlton what! The Ritz Carlton seemingly never gives free suite upgrades to anyone or for any reason. This too was a benefit I didn’t know was available to me until I started digging into the benefit of the merged programs.

By now two questions are probably bouncing around in your head. One, why didn’t I know about the two suite upgrade benefits? Two, what does this have to do with managing pharmacy benefits? Let’s tackle the first question.

Marriott’s policy around these suite upgrades, while not published, is clear. That is not to be proactive in educating it’s members about these two particular benefits. It would be easy to blame Marriott for no one ever mentioning the benefits to me but I won’t. That’s the easy way out. The reason I didn’t know is because I wasn’t proactive in learning about all the options available. It doesn’t matter that some of the information is in the fine print.

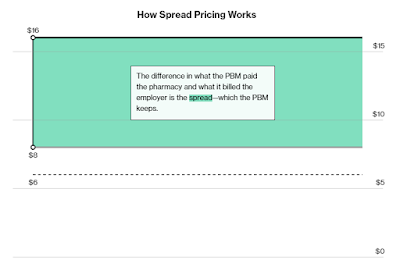

So what does this have to do with managing pharmacy benefits? Simple. The reason so many employers are overpaying is they [you] are not proactive and reluctant to invest the time to learn how to properly manage pharmacy benefits. Like Marriott, non-fiduciary PBMs have learned how to leverage the purchasing power of unsophisticated clients to their financial advantage.

Having knowledge about the upgrade benefits would have saved me a lot of time and money. I wouldn’t have purchased as much chapstick to kiss up to the front desk staff for a free upgrade. For you, the stakes are much much higher. Having more knowledge about managing pharmacy benefits could save an employer millions of dollars, help grow a brokerage business or maybe even save someones life.