A National Drug Code or NDC is a numeric system to identify drug products in the United States. A drug’s NDC number is often expressed using eleven digits in a 5-4-2 format (xxxxx-yyyy-zz) where the first five digits identify the manufacturer, the second four digits identify the product and strength, and the last two digits identify the package size and type.

NDC codes are defined based on the labeler and Food and Drug Administration segments. The segments identify the labeler or vendor, product (within the scope of the labeler), and trade package (of this product).[1]

- The first segment, the labeler code, is 4 or 5 digits long and assigned by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) upon submission of a Labeler Code Request. A labeler is any firm that manufactures, repacks or distributes a drug product.

- The second segment, the product code, is 3 or 4 digits long and identifies a specific strength, dosage form, and formulation for a particular firm.

- The third segment, the package code, is 1 or 2 digits long and identifies package forms and sizes. In very exceptional cases, product and package segments may have contained characters other than digits.

While the labeler code is assigned by the FDA, both the product and package segments are assigned by the labeler. While in the past labelers may have had the opportunity to reassign old product codes no longer used to new products, according to the new FDA validation procedures, once an NDC code is assigned to one product (defined by key properties including active ingredients, strength, and dosage form) it may not be later reassigned to a different product.

The acronym HCPCS originally stood for HCFA Common Procedure Coding System, a medical billing process used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Prior to 2001, CMS was known as the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA). HCPCS was established in 1978 to provide a standardized coding system for describing the specific items and services provided in the delivery of health care.[2]

Such coding is necessary for medical benefit drug claims submitted for Medicare, Medicaid, and other health insurance programs to ensure that insurance claims are processed in an orderly and consistent manner. Initially, use of HCPCS codes was voluntary, but with the implementation of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) use of the HCPCS for transactions involving health care information became mandatory.

Problem(s)

MBDC or medical benefit drug claim information is not as readily available as the data for retail pharmacy claims. The primary reason, I believe, is that self-insured employers are not demanding it before the services agreement is executed. Further yet, why would anyone ask for information they don’t fully understand or would have to admit they don’t understand? The costs are too high to continue ignoring this important issue.

Second, the data when available is often incomplete. In order to evaluate cost and clinical performance employers must have a data set which includes HCPCS codes, NDCs, ICD 10 diagnosis codes and that’s just for starters. This information will allow you to evaluate clinical effectiveness, optimize dosing and vailidate pricing among others.

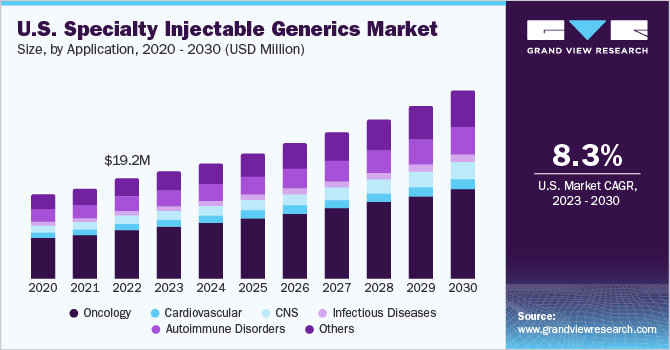

Last and most important point. The University of Minnesota College of Pharmacy published a study two years ago titled, Medical Benefit Drug Claims: Assessing the NDC Documentation Gap. The last year of the study looked at a total of 62.1 million traditional pharmacy claims and 14.6 million MBDCs (19%). For those claims, the cost was $4.74 billion and $2.64 billion, respectively. While MBDCs represented only 19% of total claim volume, they accounted for a whopping 36% of total cost! So, what’s the moral of this story?

Sources:

[1]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Drug_Code

[2]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Healthcare_Common_Procedure_Coding_System