Another opaque PBM contract bites the dust

|

| Click to Learn More |

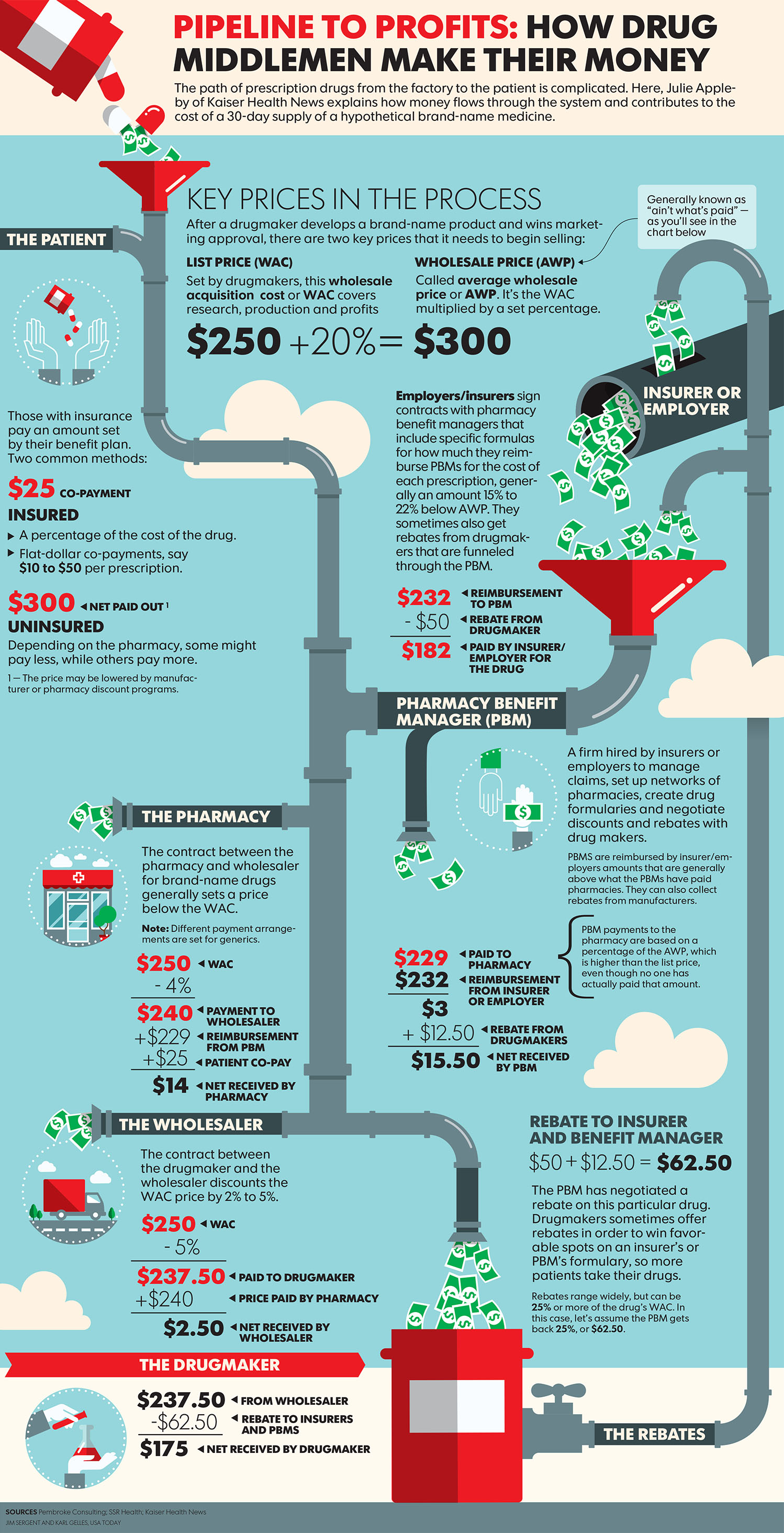

In December 2018, Connecticut’s state comptroller’s office issued a request for proposal for a new state pharmacy benefits agreement that aimed to increase transparency and eliminate “hidden wealth exchanges” between pharmacy benefit managers and drug manufacturers. A newly inked prescription drug contract between Connecticut Comptroller Kevin Lembo and CVS Caremark could save the state tens of millions of dollars a year.

Lembo, whose office administers health care and prescription benefits for more than 200,000 public employees, retirees, and their dependents, said in a news release that the “broken national model for pharmaceutical pricing” has allowed pharmacy benefit managers to “operate in the shadows,” keeping employers and patients in the dark about where their money is going.

Lembo said the state is seeking a “new paradigm in pharmacy benefit contracting” that will clearly outline administrative fees per drug in order to put an end to “hidden incentives that put drug profitability above the state plan and patients. We are putting every bidder on notice that the state of Connecticut is calling the shots on prescription drug costs and quality,” he said.

- Transparency will be increased by requiring that the entirety of all drug manufacturer payments to the pharmacy benefit manager be provided to the state, and the state will only pay the amount the pharmacy benefit manager paid each pharmacy for the cost of filling prescriptions.

- PBMs will be required to provide “frequent data feeds” to disclose all net costs “post manufacturer rebate,” so that the state has full information on the actual cost of medication. The data requirements will be subject to audits in order to verify compliance.

- New pricing models call for drug costs guaranteed by pharmacy benefit managers to be based on a per-patient or per-unit basis, rather than a discount off of the “average wholesale price.”

- PBMs are required to conduct annual market checks to ensure the state plan is getting the best market pricing.

- Drug rebates to be provided to consumers at the pharmacy counter, and requires pharmacy benefit managers to offer a reduced generic copay to consumers if a lower-cost therapeutically equivalent alternative is available (this requirement will block pharmacy benefit managers from the “troubling practice” of offering lower copays for more expensive drugs over generic ones).