Big Pharma is Slow to Allow Health Outcomes to Dictate Pricing — At Least For Now

|

| Click to Learn More |

When Novartis announced that the price of its new personalized gene therapy for cancer, Kymriah, would be $475,000, Wall Street analysts thought that was a relative bargain, but some health payers didn’t agree. Among the naysayers was Steve Miller, the outspoken chief medical officer of pharmacy benefits manager (PBM) Express Scripts.

“We need a new payment model,” declared Miller in a blog post last week. He pointed out that $475,000 is much more than the price of the average specialty drug, and with at least 1,500 experimental gene therapies in the pipeline, the potential for the health care system to be overwhelmed by high-priced, one-time cures is great.

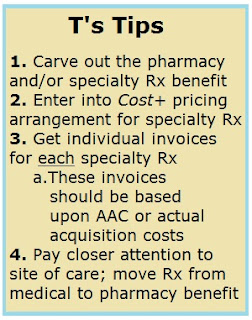

Tyrone’s Commentary:

Yesterday, I published a blog about outcomes-based rebates. Specifically, I wrote where there is smoke there is fire. Well here is the spark and I quote, “…it’s only a matter of time before other pharma companies start experimenting with value-based pricing. “Novartis is leading the pack, and there will be many laggards, but this is a huge opportunity…It’s a new era of performance-based compensation.” The article does, however, downplay drugmaker participation rate at 25%. Looking at it another way, the drugmakers who are participating in outcomes-based rebates likely represent 25% or more of all pharmaceutical manufacturer revenues which exceed $300 billion per year.

The idea of tracking health outcomes and only paying for what works—known in the industry as “value-based” pricing—isn’t new. In fact, Novartis has done it before, and the company said after Kymriah won FDA approval that it is working with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to allow for payment only when patients respond by the end of the first month after the gene therapy is administered.