Prescription Drug Prices: 10 Definitions All Payers $hould Know

Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) is the average price paid to the manufacturer for the drug in the United States by wholesalers for drugs distributed to retail community pharmacies and by retail community pharmacies that purchase drugs directly from the manufacturer. The health reform law excludes payments and rebates or discounts provided to certain providers and payers from the calculation of AMP.

In March of this year, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) again amended the legal definition of average manufacturer price (AMP). AMP uniquely serves to determine both a multiple source drug’s reimbursement amount and the rebate amounts for single source, innovator single source, and multiple source drugs within the Medicaid program. No other pricing metric serves this dual function.

Average Sales Price (ASP) – In 2005, Medicare began to pay for most drugs using an entirely new methodology based on ASP rather than AWP. Unlike AWP and WAC, there is a specific method to calculate ASP set forth in the MMA and the Act. Section 1847A(c) of the Act, as amended by the MMA, defines ASP as a manufacturer’s unit sales of a drug to all purchasers in the United States in a calendar quarter divided by the total number of drug units sold by the manufacturer in that same quarter.

The ASP is net of any price concessions such as volume, prompt pay, and cash discounts; free goods contingent on purchase requirements; chargebacks; and rebates other than those obtained through the Medicaid drug rebate program. Certain sales are exempt from the calculation of ASP, including sales at a nominal charge.

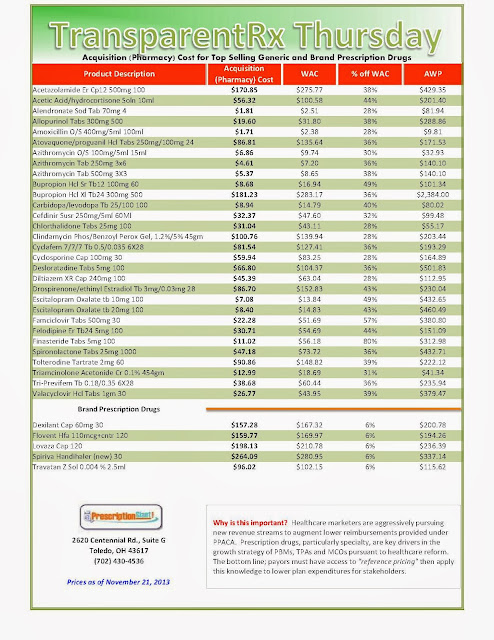

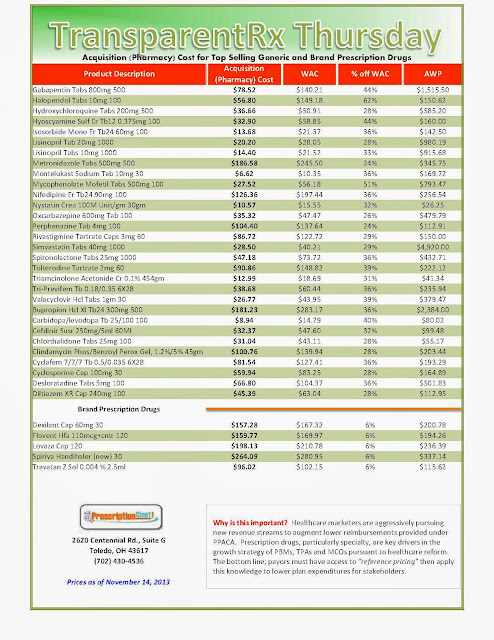

Average Wholesale Price (AWP) is not based on actual transactional, marketplace price data. Despite its name and its sometime use as a price index, the published AWP is not an average of actual wholesale prices. It is not intended to represent, and cannot be assumed to reflect, actual transaction prices.

A wholesaler or other direct purchaser from a pharmaceutical manufacturer may agree to sell its products to one or more of its customers at prices that on their face are effectively lower than the published AWP.

AWP information does not reflect any such lower pricing that may be made available in actual purchase transactions through a variety of methods, including, but not limited to, purchase, prompt-pay or other discounts, volume or other rebates or credits, or a variety of other price reduction arrangements.

Direct Price (DP) is the price directly reported to AWP publishers by a manufacturer as the list price at which non-wholesalers and healthcare providers may purchase drug products from that manufacturer. These publishers generally do not receive a reported DP for drugs that are sold by a manufacturer exclusively through wholesalers, although in some cases both a DP and a WAC may be provided at the manufacturer’s discretion.

DP does not represent an actual sales price in any single transaction or group of transactions between a manufacturer and a non-wholesaler or healthcare provider, as any manufacturer may agree to sell its products to one or more customers at a lower price through any number of methods, including, but not limited to, discounts, rebates, credits or other net price reduction arrangements.

Federal Supply Schedule (FSS) are prices paid to manufacturers by the VA, other federal agencies, and certain other entities, such as Indian tribal governments, are set by the Federal Supply Schedule (FSS). Under the Veterans Health Care Act of 1992, manufacturers must make drugs available to covered entities at the FSS price as a condition of eligibility for Medicaid reimbursement.

FSS prices are negotiated with manufacturers by the VA.15 In general, the FSS price may be no higher than the lowest contractual price charged by the manufacturer to any non-federal purchaser under similar terms and conditions. In order to determine this price, manufacturers supply the VA with information on price discounts and rebates offered to different customers and the terms and conditions involved.

Under certain conditions, the VA may accept an FSS price that is higher than the price offered to some non-federal customers. According to the GAO, average FSS prices are more than 50 percent below the non-federal average manufacturer’s price.

Ingredient Cost

- BRAND INGREDIENT COSTS – the discount from the list price, also called the Average Wholesale Price or AWP. Typical discounts range from AWP-12% to AWP-15%. A PBM may contract with a retail pharmacy at AWP-15% and then offer you an average discount of AWP-12%, keeping the difference. This is called a “spread” or “differential pricing.” Each percentage point of withhold is worth approximately $0.60 per script.

- GENERIC INGREDIENT COSTS – generic discounts are priced in one of two ways: (1) as an AWP discount or (2) at a Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC). There is usually a large gap between these pricing elements – about $6.40 per prescription. Ask your PBM to price out the top 50 generics used in the previous year, giving you both the list price and the discounted pricing (either MAC or AWP MAC) and disclose whether your MAC pricing is cost effective. Interestingly, PBM’s derive revenue from MAC programs by contracting with pharmacies at MAC pricing and charging you the AWP discount. This is another form of differential pricing.

Some of the factors that PBMs consider to choose products for inclusion on a list are availability of the product in the marketplace, whether the product is obtainable from more than one manufacturer, how the product is rated by the FDA in relation to the innovator drug and price differences between the brand and generic products. However, there is no standardization in the industry as to the criteria for the inclusion of drugs on MAC lists or for the methodology as to how the maximum price is determined, changed or updated.

Suggested Wholesale Price (SWP) is the price that a manufacturer suggests wholesalers charge when selling the manufacturer’s drug to the wholesaler’s customers, as reported by the manufacturer. The SWP does not necessarily represent the actual sales price used by a wholesaler in any specific transaction or group of transactions with its own customers. Wholesalers determine the actual prices at which they sell drug products to their respective customers, based on a variety of competitive, customer and market factors.

Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) is the price directly reported to publishers, like Wolters Kluwer Health, by a manufacturer as the list price at which wholesalers may purchase drug products from that manufacturer. WAC does not represent an actual sales price in any single transaction or group of transactions between a manufacturer and a wholesaler, as any manufacturer may agree to sell its products to one or more customers at a lower price through any number of methods, including, but not limited to, discounts, rebates, credits or other net price reduction arrangements.

Click here to register for: “How To Slash the Cost of Your PBM Service, up to 50%, Without Changing Providers or Employee Benefit Levels.”

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)