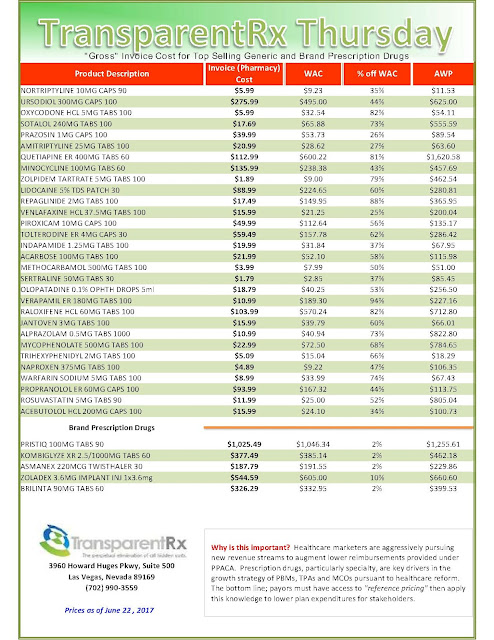

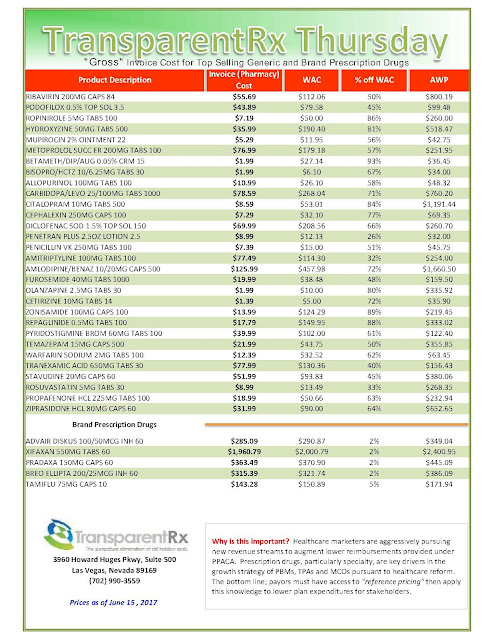

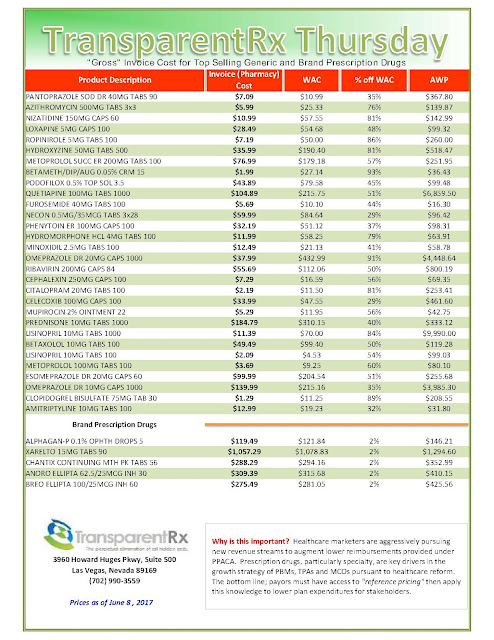

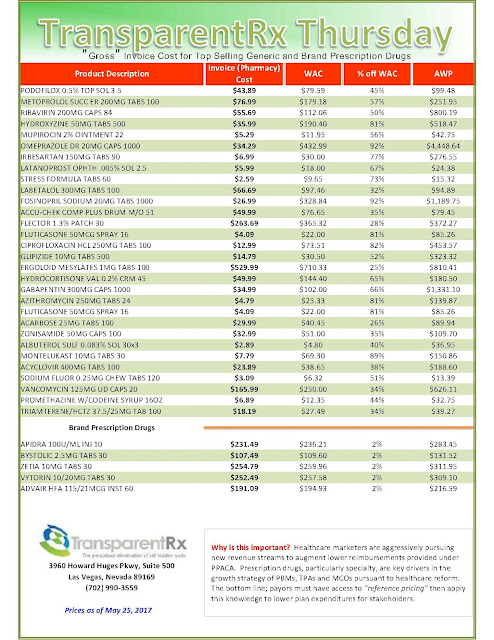

Reference Pricing: “Gross” Invoice Cost for Popular Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs (Volume 172)

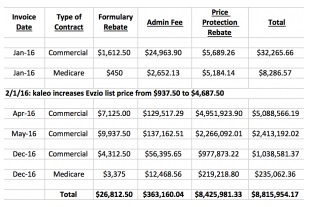

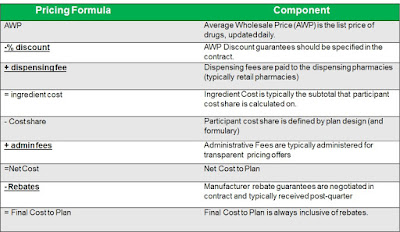

The costs shared here are what the pharmacy actually pays; not AWP, MAC or WAC. The bottom line; payers must have access to actual acquisition costs or AAC. Apply this knowledge to hold PBMs accountable and lower plan expenditures for stakeholders.

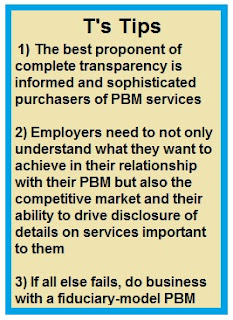

Step #1: Obtain a price list for generic prescription drugs from your broker, TPA, ASO or PBM every month.

Step #2: In addition, request an electronic copy of all your prescription transactions (claims) for the billing cycle which coincides with the date of your price list.

Step #3: Compare approximately 10 to 20 prescription claims against the price list to confirm contract agreement. It’s impractical to verify all claims, but 10 is a sample size large enough to extract some good assumptions.

Step #4: Now take it one step further. Check what your organization has paid, for prescription drugs, against our acquisition costs then determine if a problem exists. When there is a 5% or more price differential (paid versus actual cost) we consider this a problem.

Multiple price differential discoveries means that your organization or client is likely overpaying. REPEAT these steps once per month.

— Tip —

Always include a semi-annual market check in your PBM contract language. Market checks provide each payer the ability, during the contract, to determine if better pricing is available in the marketplace compared to what the client is currently receiving.

When better pricing is discovered the contract language should stipulate the client be indemnified. Do not allow the PBM to limit the market check language to a similar size client, benefit design and/or drug utilization. In this case, the market check language is effectually meaningless.