Value-Based Contracts Slowly Picking Up Steam

Value-based contracts (sometimes referred to as risk-sharing agreements or outcomes-based contracts) are a type of innovative payment model that brings together two key stakeholders—health care payers and biopharmaceutical manufacturers—to deliver medicines to patients. Under value-based contracts, biopharmaceutical manufacturers and payers agree to link coverage and reimbursement levels to a drug’s effectiveness and/or how frequently it is utilized. There are three types of value-based solutions:

Value-based contracts (sometimes referred to as risk-sharing agreements or outcomes-based contracts) are a type of innovative payment model that brings together two key stakeholders—health care payers and biopharmaceutical manufacturers—to deliver medicines to patients. Under value-based contracts, biopharmaceutical manufacturers and payers agree to link coverage and reimbursement levels to a drug’s effectiveness and/or how frequently it is utilized. There are three types of value-based solutions:

Tyrone’s Commentary:

These manufacturer revenues (rebate dollars) are in your PBM contract albeit the fine print. Most PBMs will try to exclude plan sponsors from participating in these cost-offsets but don’t be fooled. You are entitled to every penny.

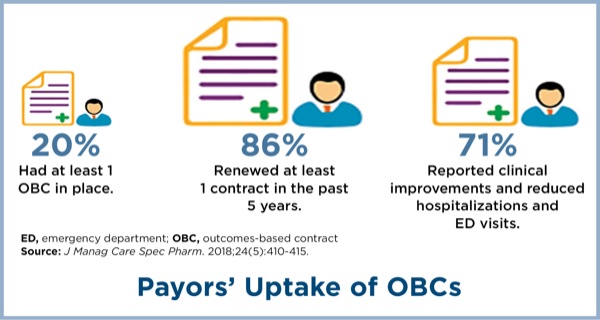

There are several potential factors limiting manufacturers’ interest in outcomes-based contracting, including a potential inability to obtain accurate data and outcomes measures, inability to discuss information that is outside the FDA-approved label, and regulatory barriers that prevent disclosing information, according to a recent AMCP membership survey (J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2018;24[5]:410-415).

The same survey found that payors, too, were concerned with identifying simple and easily measurable outcomes, wanted greater risk sharing with manufacturers, and were concerned with meeting a sufficient patient population to make the agreement worthwhile.