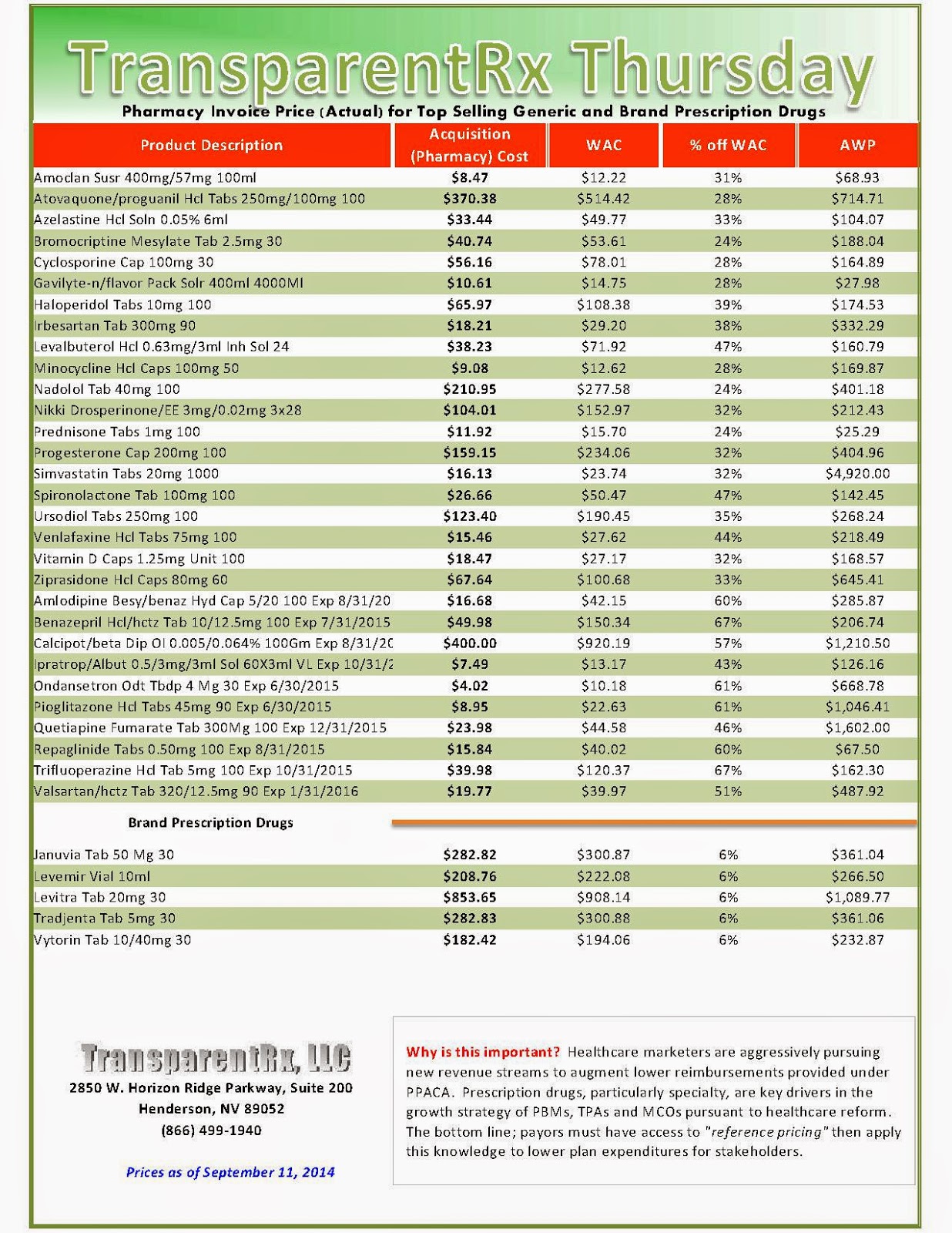

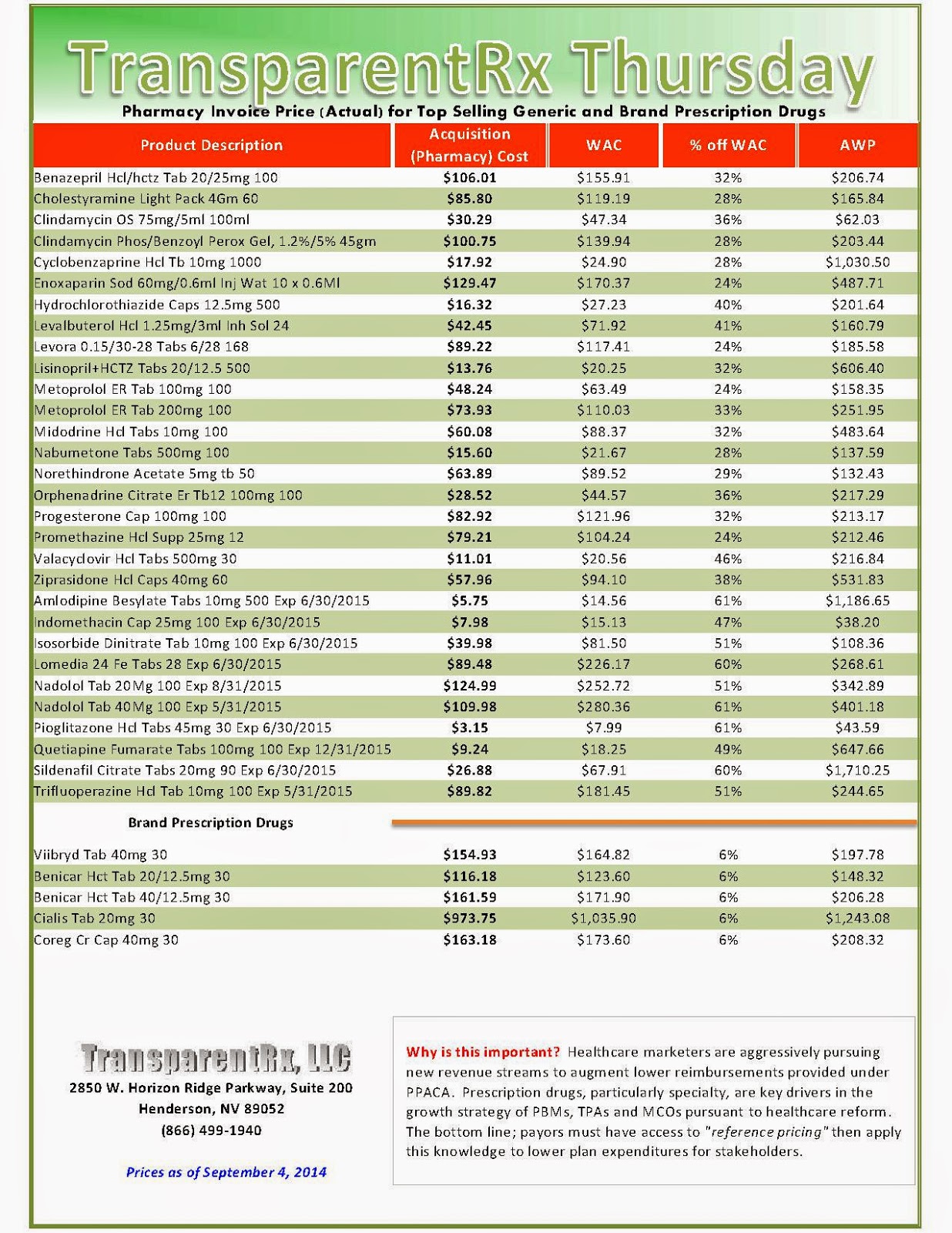

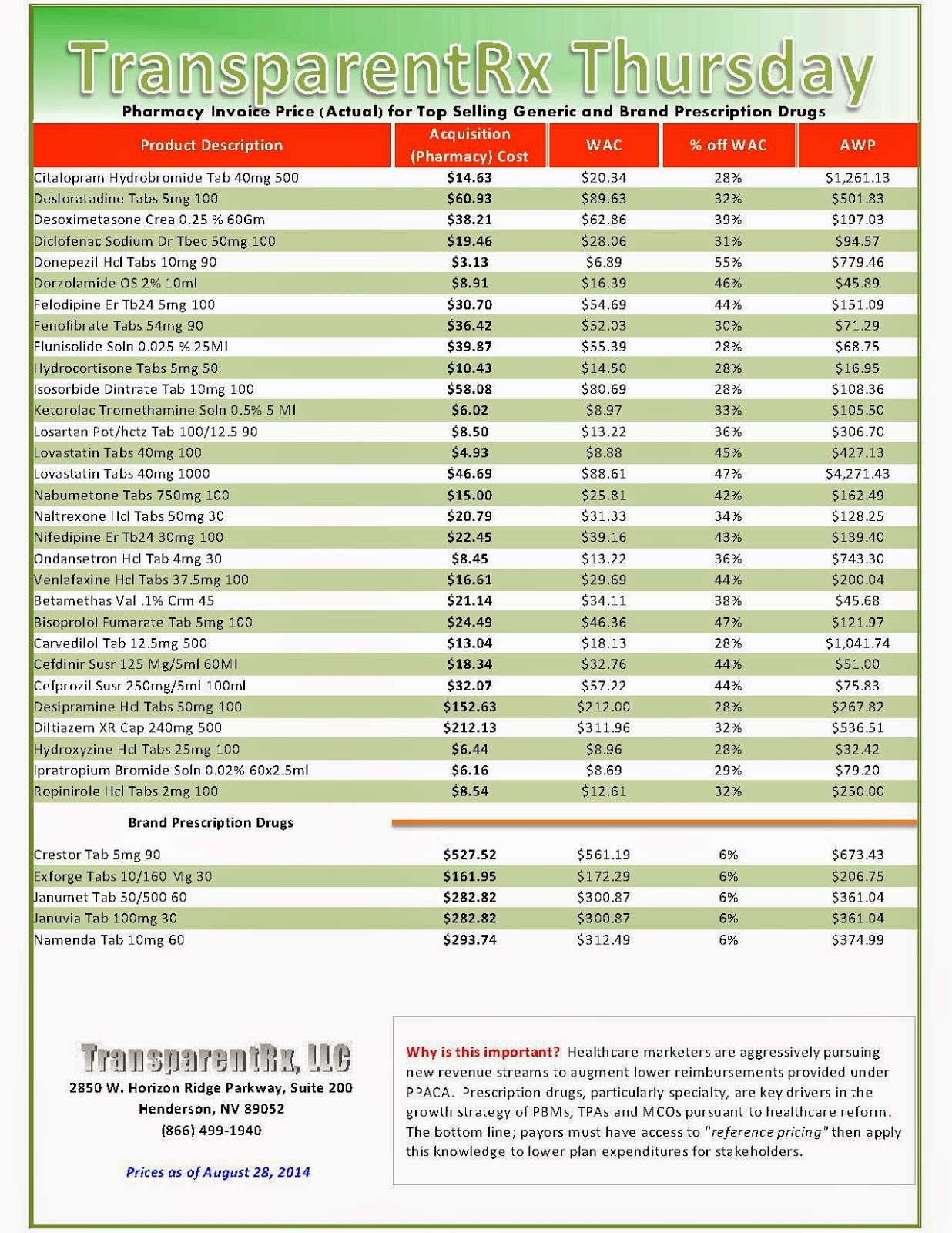

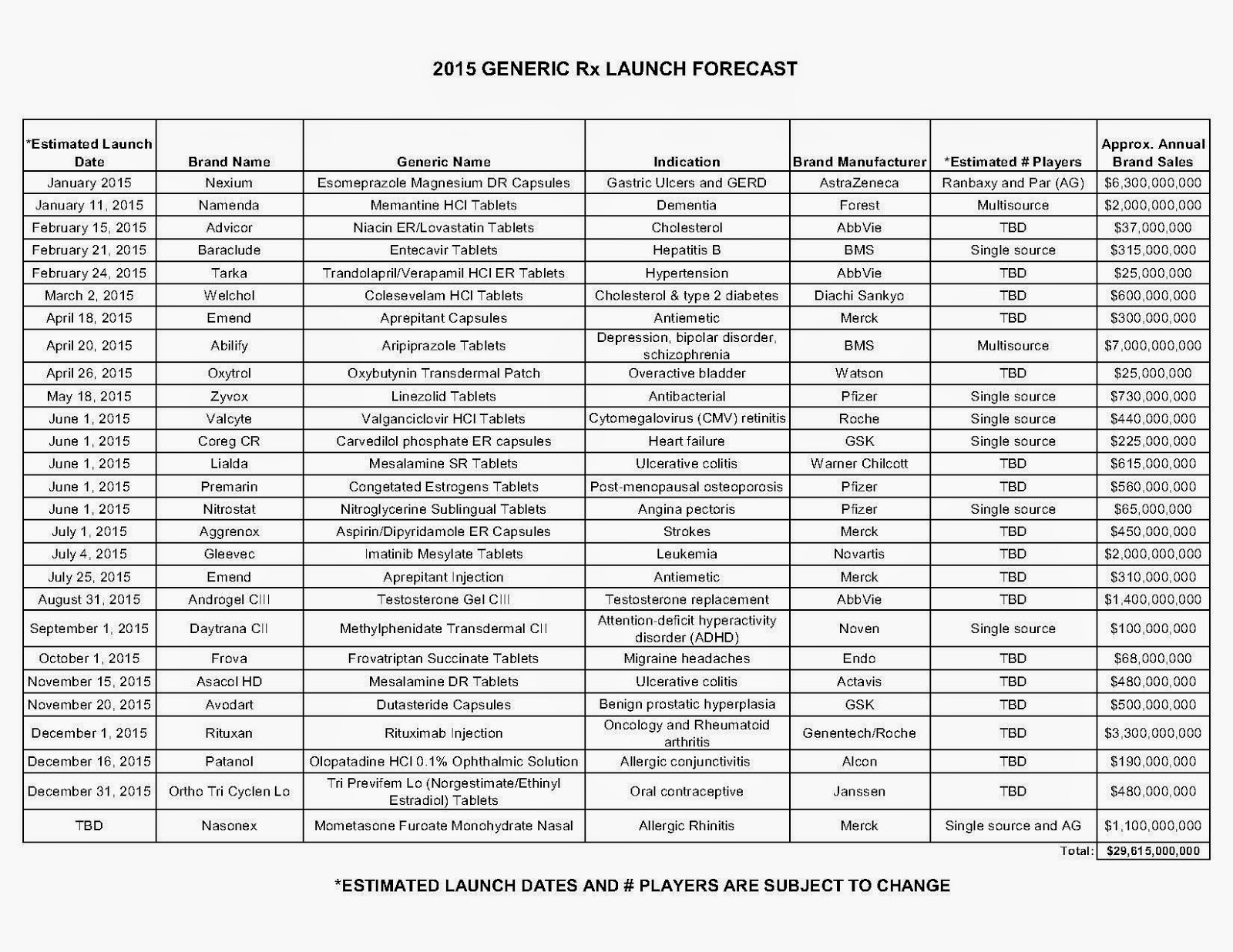

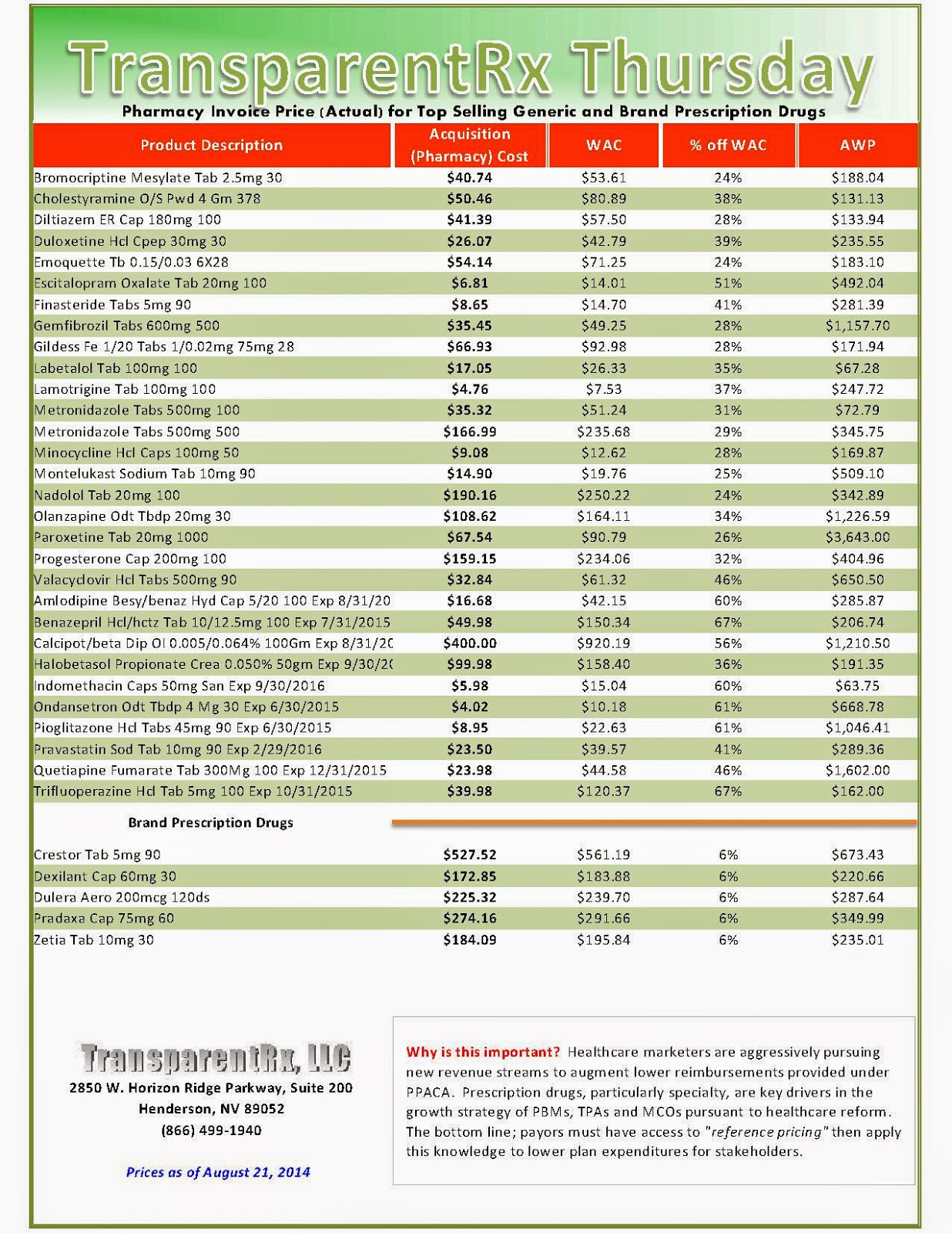

Reference Pricing: Pharmacy Invoice Cost (ACTUAL) for Top Selling Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs

The costs shared below are what our pharmacy actually pays; not AWP, MAC or WAC. The bottom line; payers must have access to “reference pricing.” Apply this knowledge to hold PBMs accountable and lower plan expenditures for stakeholders.

| How to Determine if Your Company [or Client] is Overpaying |

Step #2: In addition, request an electronic copy of all your prescription transactions (claims) for the billing cycle which coincides with the date of your price list.

Step #3: Compare approximately 10 to 20 prescription claims against the price list to confirm contract agreement. It’s impractical to verify all claims, but 10 is a sample size large enough to extract some good assumptions.

Step #4: Now take it one step further. Check what your organization has paid, for prescription drugs, against our pharmacy cost then determine if a problem exists. When there is a 5% or more price differential (paid versus actual cost) we consider this a problem.

When better pricing is discovered the contract language should stipulate the client be indemnified. Do not allow the PBM to limit the market check language to a similar size client, benefit design and/or drug utilization. In this case, the market check language is effectually meaningless.

Click here to register: “How To Slash the Cost of Your PBM Service, up to 50%, Without Changing Providers or Employee Benefit Levels.” [Free Webinar]

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_2.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)