Plan sponsors are focusing hard on specialty pharmacy costs for 2017, looking at unbundling specialty pharmacy from PBM services and considering contracts with closed-door specialty pharmacies as a way to control costs, pharmacy benefit insiders tell DBN.

At the same time, employers are pursuing retail networks that sell a 90-day supply of medication, point-of-sale rebates and more granular formulary strategies to further hone their 2017 strategies and manage a benefit that’s been getting some unfavorable public attention.

“I think 2017 will be a very active year for contracting and price negotiation in the industry,” says Josh Golden, area senior vice president, client development at Arthur J. Gallagher & Co.’s Solid Benefit Guidance consulting arm.

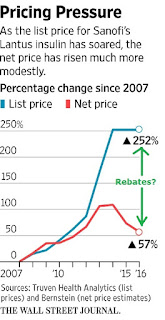

“Clients are realizing that annual contract housekeeping is needed to keep pace with the financial dynamics of the industry,” Golden tells DBN. “The past year has brought about significant changes in industry economics — the growth of inflation protection [clauses], increasing reliance on patient-assistance funding — and employers are rightfully worried that their contracts are out of sync with the realities of the marketplace.”

In particular, specialty pharmacy management has been moving beyond what Golden calls the “basic blocking and tackling” of prior authorizations and formulary management.

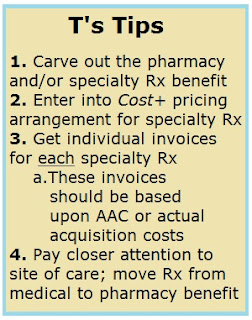

“Our larger clients are now starting to manage specialty holistically across their pharmacy and medical plans, pursuing site-of-care strategies to optimize cost, and balancing their benefit designs to ensure proper alignment,” he says. “And more progressive plan sponsors are exploring drug-specific specialty copays, specifically tailored to capitalize on patient-assistance funding that’s available from manufacturers.”

David Dross, national pharmacy practice leader, Mercer Health & Benefits, also has seen this trend. He tells DBN there’s a lot more interest among plan sponsors about managing specialty pharmacy across the continuum of medical and pharmacy benefits.

“We’re starting to look at it by disease state — which one [medical or pharmacy benefit] is doing a better job on a particular disease state,” Dross says. “If we find a pharmacy plan is doing a better job managing multiple sclerosis than the medical plan, then we may say that those medications aren’t covered under the medical plan.”

Mercer last month partnered with Envolve Pharmacy Solutions and Magellan Rx Management to offer a new specialty pharmacy solution, with competitive pricing, targeted clinical management, patient-assistance program facilitation and access to limited-distribution drugs (DBN 10/7/16, p. 8).

“It appeals to consumers and is higher-touch patient management,” Dross says. Specialty pharmacy is garnering additional attention for the 2017 plan year, with a focus on tighter and more exclusive specialty formularies and recognition that specialty is a big cost driver.

Robert Ferraro, principal, national pharmacy practice at Xerox Corporation’s Buck Consultants, agrees that the issue of how to manage specialty drugs going forward is the main issue he sees for 2017.

Should Specialty Rx Be Run Separately?

“You’re starting to see larger employers consider the notion of unbundling specialty drug fulfillment and management from the PBM,” Ferraro says. “The question is whether it makes sense to bundle those services together or whether you can get better outcomes and get better management by unbundling” and hiring a closed-door specialty pharmacy such as those run by Diplomat Pharmacy Inc. or Walgreens Boots Alliance Inc.

Another question cropping up for plan sponsors in 2017 is whether a third party should provide prior-authorization services rather than the PBM, Ferraro says. “Does it make sense to have the same entity manage and approve claims when that entity stands to benefit when claims are approved?” he asks. As an alternative, plan sponsors can hire a utilization management company to handle those services.

At this point, only the largest employers are considering this issue, he says, but “there could be a lot of fast followers,” given that specialty pharmacy costs and claims for tens of thousands of dollars in drug spend are on plan sponsors’ minds.

For PBMs, all this may not be good news. “We see the prevailing model of bundling all services within the PBM one of the past, particularly for larger employers with the capacity to manage multiple vendors,” Ferraro says. “For smaller employers, that’s probably not a good model for them.”

Continue Reading >>