The percentage of employers that plan to continue offering prescription drug plans to Medicare-eligible retirees has dropped dramatically in the past two years, according to a study released May 29 by Buck Consultants L.L.C.

Fifty-five percent of employers that now provide pharmacy benefits for Medicare-eligible retirees said they plan to continue offering the benefit, down from 75 percent in the New York-based consulting firm’s 2011 survey.

Another 33 percent of employers said they were unsure if they would continue offering prescription benefits to Medicare retirees after 2014, a significant increase from the 19 percent who were unsure in the 2011 survey.

“Employers have options for controlling prescription drug costs for Medicare-eligible participants,” Paul Burns, an Atlanta-based principal at Buck Consultants, said in a statement.

“For example, since retiree drug subsidy payments are no longer tax-exempt and do not keep pace with rising drug costs, some employers are considering moving to an employer group waiver plan to take advantage of additional subsidies available as a result of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,” he said.

The subsidiary of Norwalk, Conn.-based Xerox Corp. surveyed 250 human resource and benefit managers across a range of industries and employer sizes, from less than 2,000 full-time workers to more than 20,000.

Active employees

On the whole, 99 percent of employers surveyed provide pharmacy benefits for active employees, a three-percentage-point increase from 2011, while 48 percent offer prescription coverage for Medicare-eligible retirees, according to the study.

Among employers covering retirees older than 65, the study indicated 45 percent used the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ retiree drug subsidy to offset plan costs, a decrease of five percentage points from the 2011 survey.

That decrease should not come as much of a surprise, the study noted. The healthcare reform law ended tax exemptions for CMS’ retiree drug subsidies beginning this year, and the subsidies themselves no longer keep pace with annual growth of pharmaceutical costs.

According to Buck’s study, nearly three-quarters of employers spend 16 percent or more of their total healthcare budget on pharmacy benefits.

“If not managed effectively, prescription drugs can represent a constant financial drain on company resources and undermine the return on investment of a plan sponsor’s entire healthcare benefits program,” Mr. Burns said in the statement.

Looking ahead, only 43 percent of employers said they plan to retain their current pharmacy benefit plan for retirees older than 65 after 2014. Another 31 percent said they were not sure if they will alter their plans.

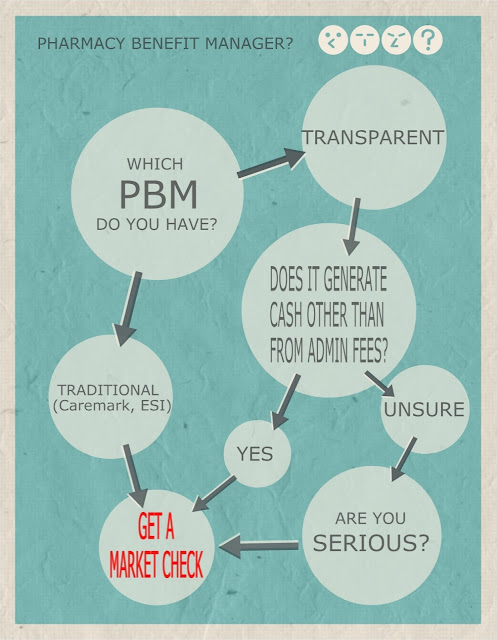

The study also noted a steady rise in the percentage of employers turning to third-party pharmacy benefit managers in search of better prices, as well as plan administration and claims management services. Sixty-one percent of employers polled in this year’s survey indicated they contract with a PBM, compared with 57 percent in 2011 and 47 percent in 2009.

“With many medications having double-digit price increases and with the continued consolidation among PBMs, this is a buyer’s market for PBM pricing,” Mr. Burns said, noting that employers should not be shy about taking an “aggressive” stance in negotiations with potential PBMs. “Any PBM contract that is 18-24 months old should be reviewed for pricing competitiveness as well as up-to-date contractual language.”

Contraceptives

Buck also surveyed employers’ positions on compliance with certain pharmacy-related provisions of the Affordable Care Act, specifically the controversial rule requiring most employers and/or their insurers to provide cost-free contraceptive prescriptions and other preventive care benefits. Small employers with fewer than 50 full-time workers that do not offer employee health benefits—as well as certain types of religious employers—are exempt from the contraceptive coverage requirements.

According to Buck’s study, one-quarter of employers polled said they plan to provide no-cost coverage for name-brand and generic contraceptive prescriptions, while another 25 percent said they would only waive co-payments for name-brand contraceptives when they are deemed medically necessary versus generic equivalents.

Twenty-seven percent of employers said they plan to waive co-payments for generic and name-brand contraceptives without a generic equivalent. Eighteen percent of employers indicated they planned to take some other approach to complying with the coverage requirement, while 5 percent said they were unsure how they would proceed, according to the 2013 Prescription Drug Benefit Survey.

This report appeared in Business Insurance magazine, a Chicago-based sister publication of Tire Business.

By Matt Dunning, Crain News Service

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)

.jpg)