The root of today’s modern PBM formed decades ago. When we asked University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy Professor Robert Valuck if patients can have a discussion about drug costs in 2016 without mentioning the role of PBMs, he gave us a succinct answer. “Not fully you can’t,” he said. Not when they’re such an integral part in the drug supply chain.

|

| Watch: Must See TV! |

“25-30 years ago, insurance companies thought, gee, we have all of these claims. We’ve got to pay these claims. Someone has to pay these claims for us, and so these little companies started up called pharmacy benefit managers,” Valuck said. Today, PBMs have a three-fold purpose, according to Valuck.

They negotiate drug prices, they build a network of pharmacies, and they build formularies. A formulary is, in essence, the list of prescriptions drugs the PBM will cover, and how much the drugs will cost. In the last few years, through the use of formularies, PBMs have taken a much more active role in telling what drugs they want their customers to take.

For 2017, Express Scripts – through its formulary – said it would cover, for example, Humulin insulin and not Novolin. Humalog insulin is on the preferred list. NovoLog is not.

Taking a drug off a major PBMs formulary can have a big impact for drug makers as removal instantly cuts into a potential customer base. For example, CVS Caremark says they have more than 75 million PBM plan members on their website. That provides PBMs with tremendous negotiating power. Typically, drug companies offer PBMs sizeable rebates to make sure their drugs can stay on the formularies.

“We’re talking 10, 20, 30 or 40% in rebates sometimes, depending on the volume,” Valuck said. Conceivably, those negotiations allow PBMs to shop for the best bargains and pass the savings along to patients. But, as Valuck pointed out, “The negotiations are private.”

That can lead to some pretty questionable deals. Last year, AstraZeneca, paid the government $7.9 million to settle allegations that the company was paying its pharmaceutical benefits manager “kickbacks” in order to stay on the formulary. Which means it was accused of paying the PBM to keep competing drugs off the formulary.

The lawsuit included allegations from whistleblowers that the drug company was giving price concessions to Medco Health, the PBM, in order to maintain “sole and exclusive” status for the drug Nexium, on certain formularies.

Among other drugs, AstraZeneca makes Byetta, a drug that treats type 2 diabetes and increased 90% since 2012. Dr. Steve Miller, the Chief Medical Officer of Express Scripts, told us the lack of transparency is critical as it allows the PBM to have all sides in the drug supply chain play off one another.

Patients, he said, can always go to the company’s website to see what they might pay for a particular drug. But, he said, when it comes to transparency, “We just don’t want it for our competitors.”

Dr. Irl Hirsch, an endocrinologist and professor of medicine at the University of Washington, has been sharply critical of that. As a diabetic himself, he has taken a particular interest in the rising cost of insulin in the U.S. “For example, we don’t know how much the pharmacy benefit manager pays for the insulin,” he told us.

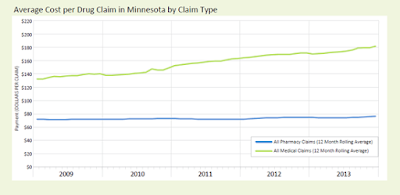

We do know, however, that a number of drug companies report stagnant or even falling net prices for their drugs at a time when the price consumers actually pay continues to rise. Sanofi, maker of Lantus insulin, reports the net price of its popular insulin “actually went down” over the last five years. Yet, according to the National Average Drug Acquisition Drug Cost database, Lantus has doubled in cost since 2012. So how can that be?

Dr. Hirsch offered this explanation, “What the manufacturers have done to keep up with the rebates they give to pharmacy benefit managers and to keep their profit margins the same, they’ve had to increase the cost.”

This is precisely what the CEO of Mylan was alluding to when she testified in front of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform in September. Her testimony surrounding the pricing of the EpiPen was roundly criticized; lost in the minutia of the discussion, however, was Bresch’s discussion of this phenomenon. “The pricing of a pharmaceutical product is opaque and frustrating,” she said.

ANTHEM LAWSUIT OPENS UP PBM PROCESS

Earlier this year, insurance giant Anthem, INC. sued Express Scripts, Inc. seeking to sever its contract with the PBM. The contract went into effect in 2009. In the suit, Anthem alleged its customers were asked to pay for prescriptions in a way that “exceeded competitive benchmark pricing by more than $3 billion annually.”

In its counterclaim, Express Scripts maintained Anthem was to blame for signing the contract in the first place. “Specifically, Anthem elected to receive $4.675 billion upfront in lower pricing during the life of the PBM Agreement,” suggested Express Scripts. “Although Anthem could have passed this upfront money through to its members – in the form of reduced drug pricing – instead, Anthem used the upfront payment to repurchase its stock.”

Dr. Miller, CMO of Express Scripts, told 9Wants to Know “the rates are what [Anthem] negotiated in that initial contract. Would they have liked the contract to be different? Obviously so, but the contract is what it is,” he added.

Tyrone’s comment: Dr. Miller is the gift that just keeps on giving! Did he tacitly confirm Express Scripts is making a boatload of cash from this deal? I’m speaking to plan sponsors when I say make certain PBM vendors are 100% aligned to your best interests; systematically verify the trust you put in them. This means re-pricing claims vs. actual acquisition costs every six months, for instance. And for those brokers and consultants who serve plan sponsors, you might want to get on the right side of the fence now. Transparency is elusive; the new way of thinking centers around fiduciary standards.

In June, Anthem members began seeking class action status for a lawsuit against Anthem and Express Scripts saying the contract ultimately caused plan participants to suffer through overpriced medications.

Donna Marshall, the Executive Director of the Colorado Business Group on Health, called the lack of pricing transparency with prescription drugs consistent with the pricing of everything in health care. “The whole thing is like the Wizard of Oz – behind the curtain,” she said. “There are a lot of levers and a lot of moving parts.”

Read more: http://www.9news.com/news/investigations/side-effects/side-effects-the-role-of-the-pbm/353602752