If a pharmacy benefits manager promises a group health plan that there will be no administrative fee for drugs, it actually could be a red flag and not a cause for celebration. It could mean the PBM is “gaming the spread” or not passing rebates through to the plan.

Plans can prevent this kind of leakage and contain costs much better if they take more active roles in managing drug benefits, according to Susan Hayes, who founded Pharmacy Outcomes Specialists of Lake Zurich, Ill. If a health plan abdicates all authority, it may end up losing influence and its ability to duck unreasonable price spikes, Hayes told attendees at the International Foundation of Employee Benefit Plans’ Annual Employee Benefits Conference in Boston on Oct. 14.

Contracting out drug benefit administration can make it difficult for plans to act in the sole interest of plan participants in certain ways, she said.

PBM Rebate Shifts Can Hurt Plans

Rebates and discounts between PBMs and drug makers can reduce drug prices for plans. Several kinds of rebates exist: (1) the drug maker rewards the PBM for putting its product on formulary; (2) the drug maker rewards the PBM for allotting a certain percentage of market share to the product in relation to comparable agents produced by competing manufacturers; and (3) the drug maker pays the PBM for market intelligence on prescribing patterns, Hayes said.

But when rebates disappear trouble can start.

PBMs might say the sole reasons they rescind preferred status is because: (1) a drug has become a source of wasteful spending; or (2) clinically appropriate alternatives exist. But a drug’s removal from preferred status may be just because the manufacturer stopped paying the PBM rebates, leaving plans wondering what happened, she said.

The Spread Is No Game

A big source of potential plan waste is “spread pricing.”

The “spread” is the difference in what PBMs charge plan sponsors for prescriptions and what they in turn pay pharmacies to dispense those prescriptions. This difference often leads to greater profits for the PBM at the expense of employers. The spread is a prime contributor to why one pharmacy may charge your plan very little and another may charge very much for the same generic medication.

According to reporting by Fortune magazine reporter Katherine Eban, Meridian Health System audited its spending on employee medications to learn the scope of spread pricing. For the antibiotic amoxicillin, Meridian was billed $92.53 when an employee filled the prescription, but its PBM paid only $26.91 to the pharmacy to fill the same prescription. That amounted to a spread of $65.62 for only one prescription.

In another instance, Meridian was billed $26.87 for a prescription of azithromycin. The PBM paid the pharmacy $5.19 to dispense the prescription, creating a spread of $21.68. While the PBM continually promised savings, Meridian paid $1.3 million in unnecessary prescription benefits costs to this vendor due to the spread, Eban alleged.

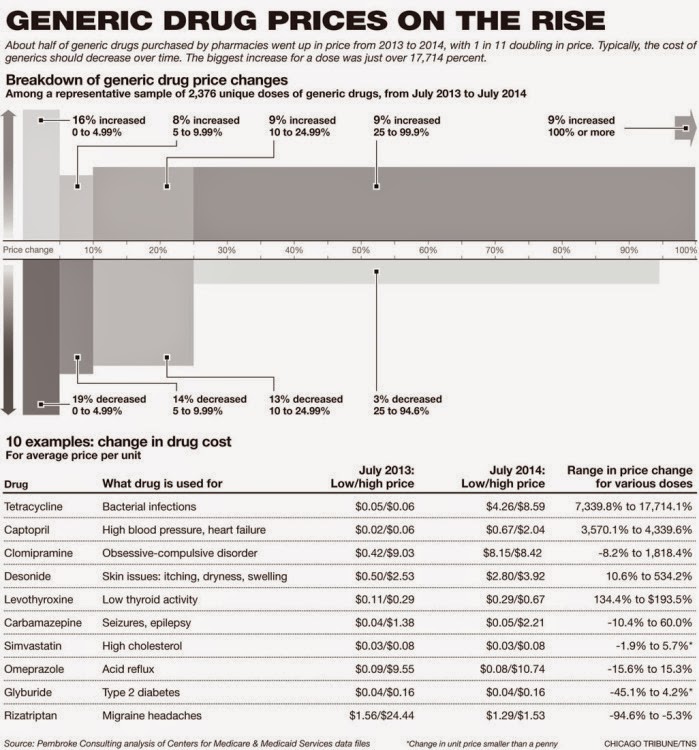

Dramatic Generic Price Increases

But bigger drug cost problems may not be the PBM’s fault: generics can be the subject of dramatic inexplicable year-to-year price variations, which the plan might not be able escape. Hayes gave the example of tetracycline 500 mg capsules, which shot up in price 177-fold from 2013 to 2014.

The problem of selected generic drugs becoming wildly expensive for unknown reasons has drawn the attention of Members of Congress.

Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt. and Sen. Elijah Cummings, D-Md., on Oct. 2 sent letters to 14 generic drug manufacturers asking why dramatic price increases had occurred in just the past few months for: Doxycycline Hyclate, an antibiotic; Pravastatin Sodium, a high cholesterol drug; Divalproex Sodium, a treatment for migraines; Albuterol Sulfate, a treatment for asthma; and several others. These drugs leapt in price five- to 50-fold in as little as six months.

Greater Plan Control

Plans can achieve savings by accepting fiduciary responsibility, Hayes told the IFEBP attendees; for example, by writing cost-savings drug management provisions into the plan document and managing drug spending in accord with that document. That way they can limit plan expenses to what’s reasonable and what can be defended. For example, many plans are finding savings by using more than three tiers of coverage, to steer utilization toward generics, or toward the most clinically appropriate brand-name medication.

A health plan that has accepted fiduciary responsibility may use tougher step-therapy rules by requiring a less expensive therapy be tried before authorizing an expensive one. In other example, plans may be able to apply coverage criteria for expensive therapies that authorize coverage at a later disease stage than the company’s PBM does.

Also, a plan may want to use a closed formulary under which it can laser out for non-covered drugs that suddenly become prohibitively expensive.

A plan may want to use a “new-to-market” exclusion that slaps a temporary moratorium on brand new therapies to allow plan committees to review them and to allow some price stability to emerge. This gives the plan time to seek out a distribution challenge, study the cost impact and seek out its own drug strategy. This could be a strategy for new specialty drugs.

If a plan takes more control, it can enact strict plan provisions against physician off-label use and then in detect such ineligible claims and preventing payment for them, she suggested.

But it is important for plans not to take drug cost-cutting in isolation, Hayes said. Limiting the cost of medications can trigger increased physician and hospital costs down the line. One study found that the “achievement” of reducing spending on outpatient drugs by 79 percent was offset by a 3-percent increase in physician and a 23-percent increase in hospital costs.

Fiduciary responsibility can cut both ways. Fiduciaries are expected to act on behalf of participants with the exclusive purpose of providing benefits to them. If plans accept ERISA fiduciary status, they might be obliged to cover medications that are expensive, and that might sometimes involve having to override a PBM exclusion, she noted. If invoking fiduciary authority to override PBM decisions goes only in one direction; that is, for plan cost savings and never for better clinical care for the patient, the plan could run into trouble down the road.

By Todd Leeuwenburgh

Click here to register: “How To Slash the Cost of Your PBM Service, up to 50%, Without Changing Providers or Employee Benefit Levels.” [Free Webinar]