Three economists were critical in creating and expounding on the hypothesis of information asymmetry or information failure: George Akerlof, Michael Spence, and Joseph Stiglitz. The three shared the Nobel Prize in economics in 2001 for their commitments.

Information Asymmetry hypothesis suggests that sellers may have more data than purchasers, slanting the cost of merchandise sold or services rendered. The theory argues that low-quality and high-quality services can command the same price, given a lack of information on the buyer’s side.

Akerlof initially contended about information asymmetry in a 1970 paper named “The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism.” In this paper, Akerlof gave a new explanation for a well-known phenomenon: the fact that cars barely a few months old sell for well below their new-car price. Akerlof’s model was simple but powerful.

Assume that some cars are “lemons” and some are high quality. If buyers could tell which cars are lemons and which are not, there would be two separate markets: a market for lemons and a market for high-quality cars. But there is often asymmetric information: buyers cannot tell which cars are lemons, but, of course, sellers know. Therefore, a buyer knows that there is some probability that the car he buys will be a lemon and is willing to pay less than he would pay if he were certain that he was buying a high-quality car. This lower price for all used cars discourages sellers of high-quality cars.

Although some would be willing to sell their own cars at the price that buyers of high-quality used cars would be willing to pay, they are not willing to sell at the lower price that reflects the risk that the buyer may end up with a lemon. Thus, exchanges that could benefit both buyer and seller fail to take place and efficiency is lost.

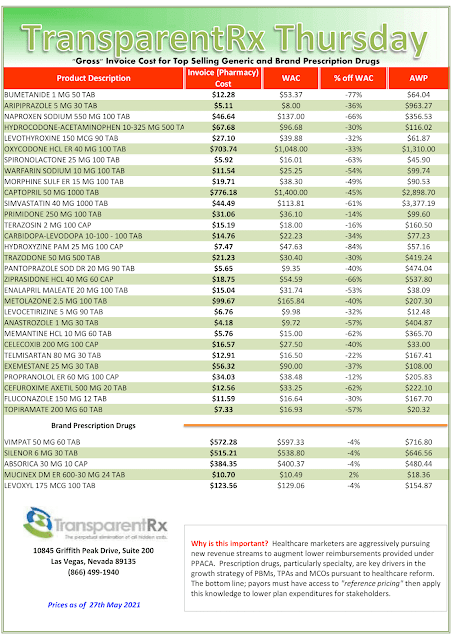

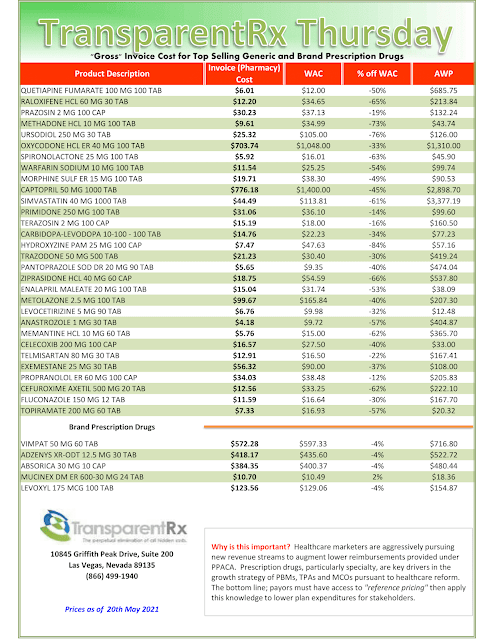

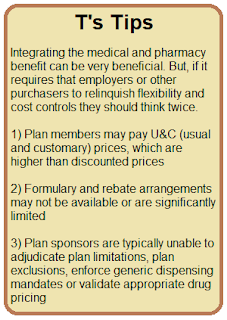

PBMs know exactly how much they are charging (management fee) for their services, but self-funded employers do not. Non-fiduciary PBMs don’t want buyers (employers) to know how much revenue they generate because it would allow better decisions on the part of their customers. Those customers, self-funded employers among others, don’t realize that in many cases the PBM’s management fee contributes more to their final plan costs than does the

ingredient cost!

A large number of the difficulties self-funded employers face come about because of something they are doing or not doing, something that changing broker, benefits consultant or even PBM won’t fix. My experience reveals that their grievances about prescription drug prices and pharmacy benefits management in general stem from the self-funded employer’s choices and constraints, not a lack of options.

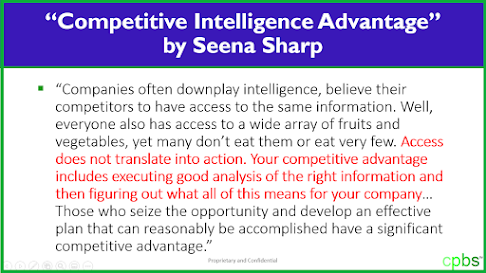

Self-funded employers are smart but they are unaware of or lacking information that might benefit them in improving their pharmacy benefit management decisions. Better decisions are the first step to improving their employer-sponsored pharmacy benefits results. The key then to getting to lowest net cost and maximizing efficiency in their pharmacy benefit program is eliminating information asymmetry which requires extensive pharmacy benefits management education and training.

“Thank you Tyrone. Nice job, good information.” David Stoots, AVP

“Thank you Tyrone. Nice job, good information.” David Stoots, AVP