Marilyn Bartlett took a deep breath, drew herself up to her full 5 feet and a smidge, and told the assembled handful of Montana officials that she had a radical strategy to bail out the state’s foundering benefit plan for its 30,000 employees and their families.

The officials were listening. Their health plan was going broke, with losses that could top $50 million in just a few years. It needed a savior, but none of the applicants to be its new administrator had wowed them.

Now here was a self-described pushy 64-year-old grandmother interviewing for the job. Bartlett came with some unique qualifications. She’d just spent 13 years on the insurance industry side, first as a controller for a Blue Cross Blue Shield plan, then as the chief financial officer for a company that administered benefits. She was a potent combination of irreverent and nerdy, a certified public accountant whose Smart car’s license plate reads “DR CR,” the Latin abbreviations for “debit” and “credit.”

Tyrone’s Takeaways:

1) Self-funded employers don’t know what they don’t know thus put too much trust in those who purport to have “the” solution but are really most interested in padding their own pockets.

2) If you’re a plan sponsor, get someone on your side who puts you first contractually not just lip service. This person must also have P&L responsibility experience from the other side (i.e. health plan, PBM or drugmaker) or at the very least trained by someone who has the requisite qualifications.

3) Don’t settle for anything less than radical transparency, Marilyn didn’t.

4) The more sophisticated you are as a purchaser the less you pay without cutting benefits to employees or raising their cost share.

5) A co-op or coalition aren’t always the better deal. They often leverage the purchasing power of members for their own financial advantage.

6) I would like to buy Marilyn Bartlett a beer. Marilyn if you’re reading this call a brotha!

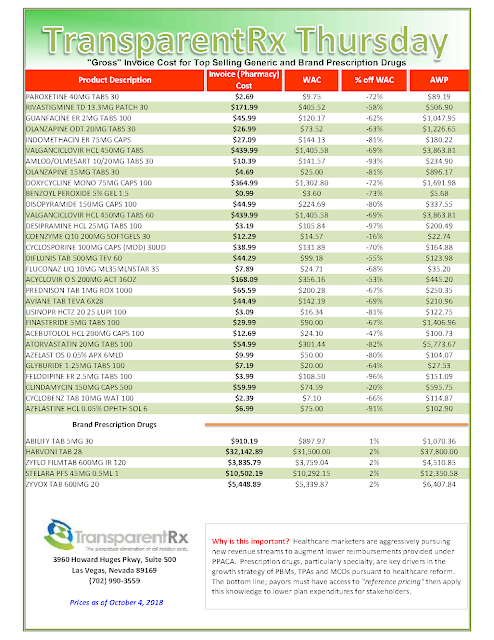

Health plans contract with separate companies, middlemen entities known as pharmacy benefit managers, to get members their medication. And everyone assured Bartlett the state’s pharmacy benefits deal was “state of the art.” But just like with Cigna, she insisted on examining it herself.

That wasn’t easy because the pharmacy benefits were run through a cooperative arrangement with other health plans, including those of universities, school trusts and counties. The state plan anchored the co-op, and the other partners were happy with the arrangement.

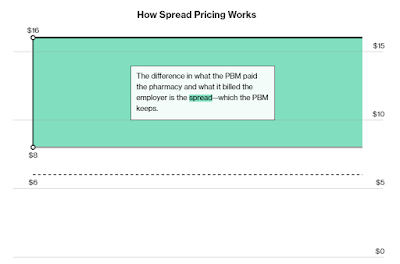

Bartlett knew that pharmacy benefit managers are notorious for including deals that boost their profits at the expense of employers. One of the common tricks is called the “spread.” A pharmacy benefit manager, for example, will tell an employer it cost $100 to fill a prescription that actually cost $60, allowing the pharmacy benefit manager to pocket the extra $40. The fine print in the contracts often allows it.

The spread is widespread. A recent report by the Ohio state auditor noted that the spread on generic drugs had cost that state’s Medicaid plan $208 million in a single year — 31 percent of what it spent.

Sure enough, when she got the contract, Bartlett found that the state plan had fallen victim to the spread.

[Read More]