Drug prices rise as big pharma profit soars

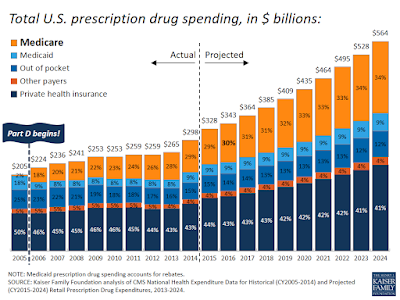

Retail prescription drug expenses accounted for about 12% of total U.S. healthcare spending in 2015, up from about 7% through the 1990s. Pharmaceutical and biotechnology sales revenue increased from $534 billion to $775 billion between 2006 and 2015, according to a recent report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office. About two-thirds of drug companies saw their profit margins increase over that period, averaging 17.1%.

Retail prescription drug expenses accounted for about 12% of total U.S. healthcare spending in 2015, up from about 7% through the 1990s. Pharmaceutical and biotechnology sales revenue increased from $534 billion to $775 billion between 2006 and 2015, according to a recent report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office. About two-thirds of drug companies saw their profit margins increase over that period, averaging 17.1%.

The GAO, along with other policy experts and government institutions, set out to identify the drivers behind one of the fastest-growing expenses in healthcare. Rising drug prices have caused hospitals and consumers to put off treatment or find workarounds that aren’t as effective. Surging pharmaceutical costs coupled with looming policy uncertainty have caused providers to cut back on hospital expenditures that would improve operations.

The GAO found that much of the rise in drug spending, which is expected to increase by nearly 8% in 2018, was fueled by the use of expensive brand-name drugs, although some pharmaceutical companies have increased generic drug prices as well. Also, limited competition has inflated drug prices while consolidation among some of the largest pharmaceutical companies has stifled research and development spending and new patents issued, research shows.