With specialty drug spending soaring 60% in the past five years, large

health systems have jumped into the specialty pharmacy business to assert some control over those costs by dispensing the drugs to their patients and covered employees.

Health systems say those pharmacies help them better manage outpatient drug costs. A growing number of insurance contracts and Medicare initiatives tie payments to quality metrics that reach beyond hospital stays to hold providers accountable for patients’ total medical costs, including drugs.

It’s also a robust business for those systems that can successfully negotiate with manufacturers and health plans so they can compete with the bigger players.

“It you want us to be responsible for the cost of care, allow us to be able to care comprehensively for these patients,” said Dick Schirber, a spokesman for ExceleraRx Corp., a for-profit specialty pharmacy services company owned by six health systems. Comprehensive care, Schirber said, includes managing the very expensive prescriptions that patients take at home for cancer or chronic diseases, so that providers have more control over waste as well as complications.

ExceleraRx provides services to system-owned specialty pharmacies, such as negotiating with drugmakers and handling data reporting.

Phoenix-based Banner Health started its own specialty pharmacy last year, taking its business away from Premier, which acquired Commcare Specialty Pharmacy in 2010 for $35.9 million. Banner employees enrolled in the system’s health plan were the pharmacy’s first customers.

Phoenix-based Banner Health started its own specialty pharmacy last year, taking its business away from Premier, which acquired Commcare Specialty Pharmacy in 2010 for $35.9 million. Banner employees enrolled in the system’s health plan were the pharmacy’s first customers.

“For everyone, everywhere, the pharmacy expense is increasing,” said Pam Nenaber, Banner’s CEO of pharmaceutical operations.

Banner Health hired three clinical pharmacists, three patient advocates and three staff members to support operations. The system also spent $1 million on a drug-dispensing robot for the specialty pharmacy’s new home-delivery service. The robot fills pill bottles, which are verified by a pharmacist before being shipped. Clinical pharmacists also talk to patients at home to answer prescription questions.

In the first year, Banner shaved about 1% off its specialty drug spending for about 1,200 workers and their families covered by the system’s employee health plan.

Health systems that own specialty pharmacies argue they can do a better job overseeing the use of the drugs they dispense. That’s because their pharmacies can easily access medical records, laboratory results and physician notes, allowing pharmacists to closely monitor the effectiveness of the drugs prescribed and react quickly when something goes wrong or patients need help.

“They know if the patient is getting the value for the high-cost drug,” said Steven Rough, director of pharmacy for the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics, which began handling transplant drugs in 2006 and expanded its specialty pharmacy in 2011.

Launching a specialty pharmacy does not require significant capital investment, and the high prices of the drugs—even sold at slim margins—make it possible to quickly see a return on that investment.

“It’s a quite viable business,” said Scott Knoer, chief pharmacy officer at the Cleveland Clinic, which opened its specialty pharmacy roughly a year ago, and advises other systems to do the same. “Get on it and get on it fast,” he said.

That’s true even as the Ohio health system expands its operations. The pharmacy is hiring more staff because the volume of prescriptions has increased about 10% a month. It now employs 25 workers, and that number is expected to reach 66 employees within three years.

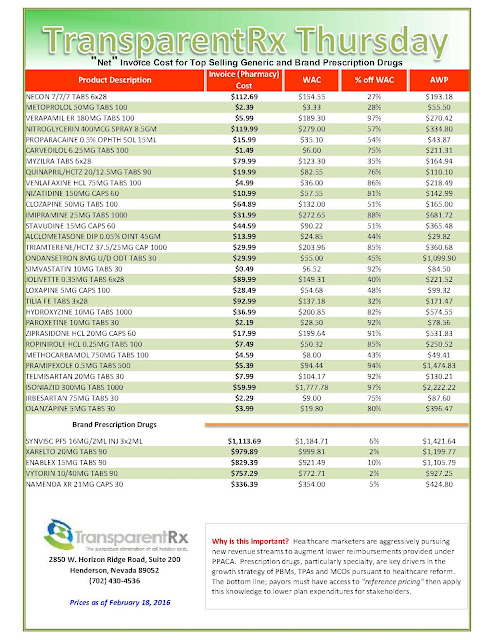

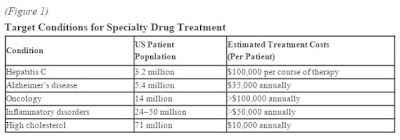

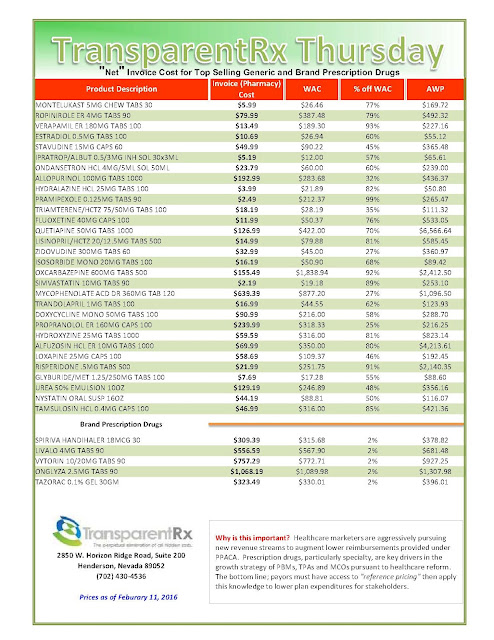

New drugs last year boosted spending for specialty pharmaceuticals 25% over the prior year, IMS Health reported in April. Specialty drugs to treat diseases such as cancer, multiple sclerosis and hepatitis C now account for one-third of drug spending. Sovaldi and other new treatments for hepatitis C boosted spending by $12.3 billion, IMS said.

Pharmaceuticals still account for just 10% of U.S. healthcare spending, but a 12.3% surge in 2014—including $12.6 billion spent on new specialty drugs to treat hepatitis C—contributed to the year’s uptick from the record-slow health spending that started with the Great Recession.

That growth makes dispensing specialty drugs an increasingly important piece of healthcare delivery, as well as an attractive business line, said John Ransom, a managing director of healthcare research at Raymond James. “It’s riding the wave of where the innovation is,” he said.

But systems will face fierce competition as they try to ride that wave, Ransom said. “It can be a tough business.”

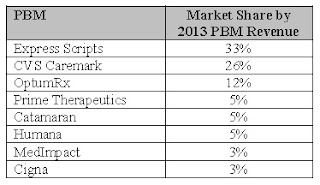

They will have to vie with national pharmacies like CVS Health, Express Scripts and Diplomat Pharmacy to be included in health insurance networks. CVS and Express Scripts also own pharmacy benefit-management companies, so they “have a vested interest in limiting the network of specialty pharmacies because they are specialty pharmacies,” Ransom said.

Pharmaceutical manufacturers also limit shipping of some of their drugs to a handful of pharmacies, in what are called limited-distribution networks.

Getting a spot in drug manufacturers’ limited networks requires intense negotiation, and the capacity to report quality and use data back to drugmakers.

ExceleraRx, launched in 2012 with investment from Minneapolis-based Fairview Health Services, helps its owners and clients with those tasks. Englewood, Colo.-based Catholic Health Initiatives, which opened its own specialty pharmacies in Kentucky and Nebraska last year, invested in ExceleraRx to “supercharge” the new business line, said Nick Barto, the health system’s senior vice president for capital finance.

However, another danger for providers is that patients may begin to see them as “the organization that’s providing the drugs that you can’t afford,” said Benjamin Isgur, director of thought leadership at PriceWaterhouseCoopers’ Health Research Institute.

But health system executives say they’ve hired staff to help patients identify discounts, coupons and other financial aid for drug costs not covered by insurance. And health systems can further market their independence from shareholders and the pharmaceutical industry.