|

| [Click to Enlarge] |

For a health plan administrator looking to improve the quality of care, reduce thoughtless use of expensive drugs, and lower costs it’s hard to see how not to impose prior authorization.

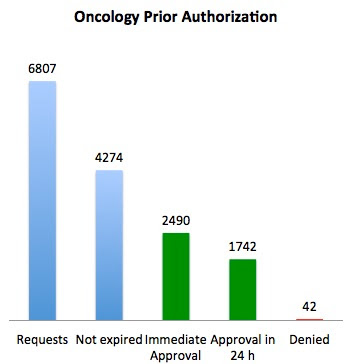

Lee Newcomber of United Health Care and colleagues reported in The Journal of Clinical Oncology Practice on a thoughtfully designed prior authorization program for chemotherapy implemented only in Florida – and compared costs in Florida compared to the rest of the Southeast, and then compared to the rest of the country. Costs went down by 9% in Florida, and went up by 10-11% in the comparison geographies. Only 42 cases (1%) were denied. Savings totaled $5.3 million for the pilot program.

The program used National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, which were digitized by a third party. Oncologists had to submit the minimal amount of information to get to a NCCN decision node, and were offered a series of choices. They only needed to get prior authorization if they were prescribing medications not listed as appropriate by NCCN.

Tyrone’s comment: PAs, for biologics, can easily run into the $400 to $500 range so be prudent in managing this service along with the associated costs. Ask your PBM who handles PAs and what, if anything, their specialty pharmacy does to help patients finance their cost share (i.e. co-pay cards, coupons, patient assitance programs and/or nonprofits). Lastly, a quarterly cost-benefit analysis could prove to be very worthwhile.

Characteristics of this program which made it far less onerous than many prior auth programs:

1) Requested the minimal amount of information necessary

2) Used guidelines that were promulgated by a trusted source, and were open source (nonproprietary)

3) Allowed providers to do “self service” if they stayed on the clinical pathway

4) Committed to 24 hour turnaround times for “non-pathway” treatment

5) Allowed “grandfathering” of patients already on “non-pathway” treatment

The high rate of administrative expiration was described as being due to administrative errors, duplicates, out-of-state physicians mistakenly using the system, and change in patient status.

This program, which the authors call “decision support” rather than “prior authorization,” replaced a previous program that asked physicians to follow the NCCN guidelines and denied claims if they went outside the guidelines without prior authorization. The previous program led to many calls for “permission” that were unnecessary, and led to 7% denial rates.

Doctors and patients will continue to despise prior authorization programs. But it appears that this program was able to save significant dollars, keep more patients on an NCCN pathway, and minimize hassles. It’s a good model that should be replicated elsewhere.