The price of the same prescription drug can vary by hundreds or even thousands of dollars, depending on where you buy it, according to a new report by the U.S. Public Interest Research Group which surveyed hundreds of pharmacies and found large price differences for identical medications.

Adam Garber is the consumer watchdog for the U.S. PIRG. The group surveyed more than 250 pharmacies across the country for the cash prices of common medications, the price someone pays if they don’t have insurance or are under-insured and do not qualify for coupons or savings programs sometimes offered by drug manufacturers.

Tyrone’s Commentary:

While the study looked at only cash transactions, the premise is consistent with insured persons. The difference is that the employer picks up most of the tab. For many employers, there is a huge opportunity to cut costs by nudging members to smaller independent pharmacies. Those limited networks being pitched by large chains can be a trap. It’s a popular tactic in the pharmaceutical supply chain; that is bait and switch.

When I was an operator, a mail-order pharmacy owner, we had a wholesale contract with one of the Big Three wholesalers. You know who they are; Mckesson, Cardinal Health and AmerisourceBergen. Like most independent pharmacies, options were limited in terms of where to buy brand drugs. For generics competition was/is much more fierce.

But, when entering into an agreement with one of these big wholesalers they can require pharmacies to purchase as much as 80% of their inventory from them to remain compliant. Because secondary wholesalers don’t carry nearly enough inventory, it’s a catch 22. The big three wholesalers overcharge, especially for generics, now that the independent pharmacy can’t shop anywhere else. Sound familiar?

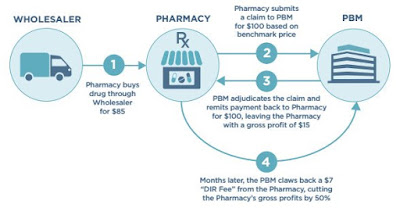

The limited or preferred networks offered by large pharmacy chains, in conjuntion with coalitions and non-fiduciary PBMs alike, often employ similar tactics they’re just not as conspicuous. A PBM or coalition could meet its performance guarantee on the front-end but that performance can be distorted hiding the true cost.

NDC upcharging, repackaging, DAW rules or DIR fees are just a few of the hidden cash flow tactics which make network performance look much better than it really is. Take my word for it, we run pharmacy switch analyses and aren’t surprised when we find $1 million savings on a $15 million annual Rx spend just by nudging members to lower cost pharmacies.

The study found consumers could save anywhere from $100 to $5,400 a year just by price shopping. In Ohio, they found the same inhaler being sold for $11.99 at one pharmacy and $1,136 at a different pharmacy. In North Carolina, a generic medicine to lower cholesterol could cost $7 or $393 depending on where it was purchased.

[Read More]