Days before Pfizer Inc. was to set the price for a new breast-cancer drug called Ibrance, it got a surprise: A competitor raised the monthly cost of a rival treatment by nearly a thousand dollars. Pfizer was left wondering if its list price of $9,850 a month for the pills was too low.

It was a tricky issue. Drug companies have been reaching for new heights of pricing. They routinely raise the cost of older medicines and then peg new ones to these levels.

Yet Pfizer knew setting a price too high for Ibrance might backfire. It could antagonize doctors and prompt health insurers to make prescribing the pills a cumbersome process with extra paperwork that doctors dislike.

A look at Pfizer’s long journey to set Ibrance’s price—a process normally hidden from view—illuminates the arcane art behind rising U.S. drug prices that are arousing criticism from doctors, employers, members of Congress and the public.

The average cost of a branded cancer drug in the U.S. is around $10,000 a month, double the level a decade ago, according to data firm IMS Health. Cancer doctors say high costs are unavoidable because all of the options are pricey.

Pfizer’s multistep pricing process shows drugmakers don’t just pick a lofty figure out of the air. At the same time, its process yielded a price that bore little relation to the drug industry’s oft-cited justification for its prices, the cost of research and development.

Instead, the price that emerged was largely based on a complex analysis of the need for a new drug with this one’s particular set of benefits and risks, potential competing drugs, the sentiments of cancer doctors and a shrewd assessment of how health plans were likely to treat the product.

In the end, “we went to the right point where patients get the maximum access, payers will be OK and Pfizer will get the [returns] for a breakthrough product,” Dr. Bourla said.

The process began in November 2011 when Mace Rothenberg, a scientist who oversees Pfizer’s development of cancer drugs, flew to California to review early clinical-trial data on a laboratory compound.

Then called simply PD-0332991, it grew out of work on proteins that help regulate how cells form and divide. In cancer, some of these can shift into overdrive. The research on this won a Nobel Prize. It also set off a hunt by drugmakers for a way to put the brakes on the overactive proteins, called cyclin-dependent kinases.

Visiting Pfizer labs in La Jolla, Dr. Rothenberg saw a slide with two curves veering far apart. It showed that the length of time before breast-cancer patients’ disease progressed was twice as long for those who took Pfizer’s compound in addition to an existing drug versus patients getting just the older drug.

“I think we have something special,” Dr. Rothenberg told the scientists leading the research.

When he got back to New York, he began talking up the compound to win the internal investment needed to develop it, as well as to involve others who would eventually set a price. Pfizer wasn’t going to fund further clinical testing and other development costs if it couldn’t anticipate good financial returns from a resulting drug.

In this case, the opportunity was clear. Pfizer’s novel compound targeted advanced breast cancer fueled by estrogen—a disease for which existing therapies, a decade or more old, offered only a modest extension of life. A drug that could do better would fill an unmet need and could be priced accordingly. So in 2012, while scientists continued their work, Pfizer employees on the commercial side started on the market analysis that would eventually lead to a pricing decision.

More clinical results arriving in December 2012 supported the compound’s promise, but also showed it was associated with lower counts of infection-fighting blood cells. The studies weren’t long enough to answer a key question: whether the compound helped people live longer.

They were encouraging enough to keep the Pfizer pricing team going, though. The team began interviewing cancer doctors, seeking to gauge interest in a possible drug with this one’s profile of benefits and risks.

Importantly, Pfizer wanted to know what the oncologists would consider comparable treatments.

Among the doctors consulted was Debu Tripathy, then co-leader of the Women’s Cancer Program at the University of Southern California. Dr. Tripathy, now at University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, says he was excited about the prospective drug described, though he would have liked to see evidence it extended lives.

Pfizer’s compound “looks about as good as Herceptin. Maybe you should price it like that,” Dr. Tripathy recalls telling Pfizer.

Herceptin was much cheaper than most other branded breast-cancer drugs, he knew. It cost about $4,775 a month in late 2013, according to its maker, Roche Holding AG, and data firm Truven Health Analytics.

Dr. Tripathy says Pfizer staffers told him it would be better to compare their compound to newer drugs. These are much costlier than Herceptin. Pfizer says Herceptin wouldn’t have been a good benchmark because it wasn’t one of the newest drugs in use and because of differences in how it is taken, the kind of cancer it treats and the length of time it stalls tumor growth.

In 2013, Pfizer hired outside firms to conduct hourlong interviews with more than 125 cancer doctors in six cities, while commercial staffers observed. Doctors said they were impressed, and many said that despite having to monitor patients for infections, they would prescribe “Product X” if the price was reasonable.

Most of the doctors, according to two Pfizer staff members, pointed to three drugs the company should consider as pricing benchmarks: Kadcyla and Perjeta from Roche and Afinitor from Novartis AG.

Like Herceptin, two of these differed from Pfizer’s drug in the kind of breast cancer treated and in how they were administered. Only Afinitor closely paralleled Pfizer’s compound by attacking the same type of breast cancer and being in pill form.

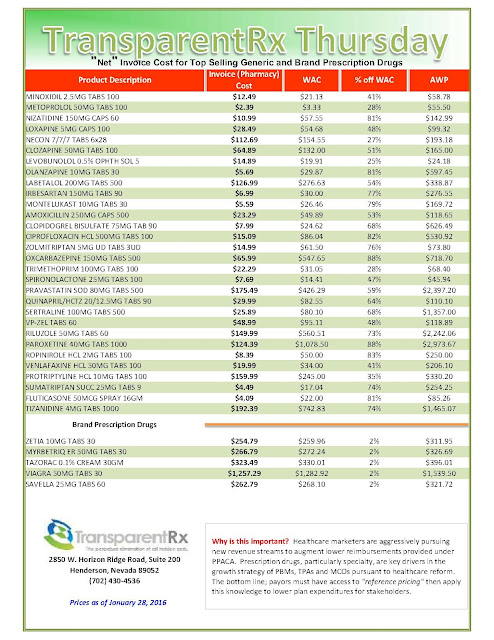

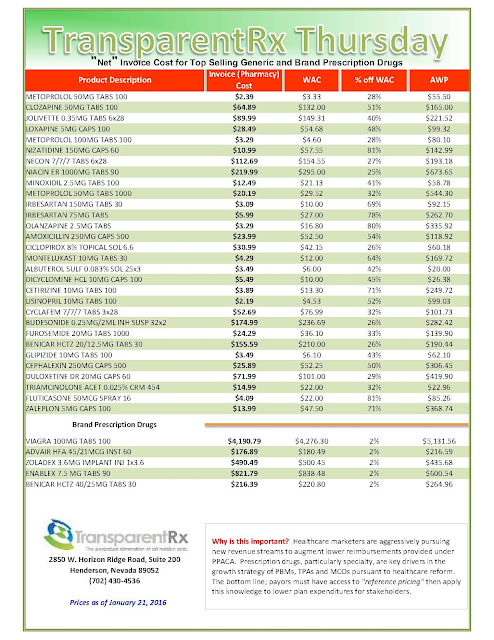

For all three, the cost of treating a patient for a month was between $9,000 and $12,000, including any other drugs that had to be taken with them. These are list prices, from which health plans and insurers negotiate discounts of 20% or so.

Competing factors

The company wanted a price that would maximize its revenue without deterring health plans or keeping the drug from getting to patients it could help. Dr. Bourla recalls telling staff members in late 2014 that the company had “a moral obligation”: The patients had a deadly disease that this drug could help, and “it is our responsibility to get it to them.”

It was time to talk to insurers.

Pfizer hired firms that surveyed more than 80 health-plan officials such as medical directors and pharmacists. They were asked what restrictions, if any, they might place on a drug with this one’s profile, at various monthly prices from $9,000 to $12,000.

Pfizer Pfizer executive Albert Bourla gave final approval last January to a price for the company’s new breast-cancer drug Ibrance, following a years-long process by other Pfizer officials that included testing the views of oncologists and health-plan officials.

At $11,000 a month, one official said the plan “would definitely require physicians to document medical necessity for Product X,” according to a person familiar with the surveys. It was the kind of paperwork obstacle Pfizer wanted to avoid.

Staff members put together a chart estimating the revenue and prescription numbers at various prices similar to those of the three drugs Pfizer had decided to use as benchmarks.

The chart showed a 25% drop in doctors’ willingness to prescribe the new drug if it cost more than $10,000 a month. This indicated Pfizer might collect higher returns by charging toward the lower end of its range.

Pfizer also had been talking with the Food and Drug Administration. The agency agreed in late 2014 to a speedy review, without waiting for results from an elaborate “Phase 3” clinical trial, so that patients with life-threatening conditions could get the drug earlier. This sped up the time to market by about two years.

Pfizer took steps to put the drug in patients’ hands as fast as possible after FDA approval. Oral cancer medicines aren’t dispensed at local drugstores but at specialty pharmacies that help patients gain insurance approvals, remind them to take pills and assist with side effects. Pfizer lined up 24 of these to supply the drug once approved.

Hoping to smooth the drug’s way onto health-plan lists of covered medications, Pfizer economists created a dossier containing data on clinical benefits and risks, plus—important to the plans—the likely effect on their budgets.

The economists mined electronic health records, drug-prescription tallies and health-insurance claims to estimate the number of prescriptions, costs of treating side effects and monitoring patients for infections, and spending that might be avoided if the drug kept cancer at bay longer.

The economists cited a 2012 report showing that a typical million-member commercial health plan spent $320 per member a month, of which the spending on cancer drugs came to just $4.20. Scenarios they ran indicated the new drug, if priced below $10,000 a month, would increase that spending no more than six cents.

The staff felt they finally had it. When they met in November 2014 to nail down a price, they picked a figure just below the cutoff: $9,850 a month. This would be the list price, from which health insurers and pharmacy-benefit managers would negotiate discounts and rebates with Pfizer.

The price they had picked was well below the cost of treatment involving one of the three benchmark drugs Pfizer had identified. But it was close to the price of the other two, and slightly above the price of the most direct competitor, Novartis’s Afinitor.

Then, on Jan. 6, 2015, Novartis raised Afinitor’s price 9.9%. Novartis says it adjusts prices to reflect “an evolving health-care and competitive environment,” new evidence and the need to support R&D.

The new price for the close rival drug put its monthly price $687 above what Pfizer was planning to charge.

Meeting in Dr. Bourla’s New York office three days later, Pfizer staff members mentioned that price increase. Dr. Bourla asked if Pfizer, too, should go higher.

“This may make some plans just not use it, and some will make things difficult and that will frustrate patients,” he recalls being told.

Alternatively, Dr. Bourla asked, should Pfizer charge a lower price than it was planning? Would doing so reach substantially more patients? He says staffers told him that a price closer to $9,000 a month wouldn’t improve health-plan coverage, and Pfizer would be leaving money on the table.

They were back to $9,850. “Let’s go with that,” Dr. Bourla said.

By Jonathan D. Rockoff