Adviser or Broker – which standard is most beneficial to plan sponsors?

Brokers (non-fiduciary)

- Must recommend “suitable” products, not necessarily best or least expensive

- Earn commissions or other transaction-based fees

- Must put clients interests before their own

- Most charge a fixed fee or percentage

A fiduciary duty is a legal and/or ethical relationship of confidence or trust between two or more parties. Typically, a fiduciary prudently takes care of money for another person. One party, for example a corporate trust company or the trust department of a bank, acts in a fiduciary capacity to the other one, who for example has funds entrusted to it for investment.

When a fiduciary duty is imposed, equity requires a different, arguably stricter, standard of behavior than the comparable tortious duty of care at common law. It is said the fiduciary has a duty not to be in a situation where personal interests and fiduciary duty conflict, a duty not to be in a situation where his fiduciary duty conflicts with another fiduciary duty, and a duty not to profit from his fiduciary position without knowledge and consent.

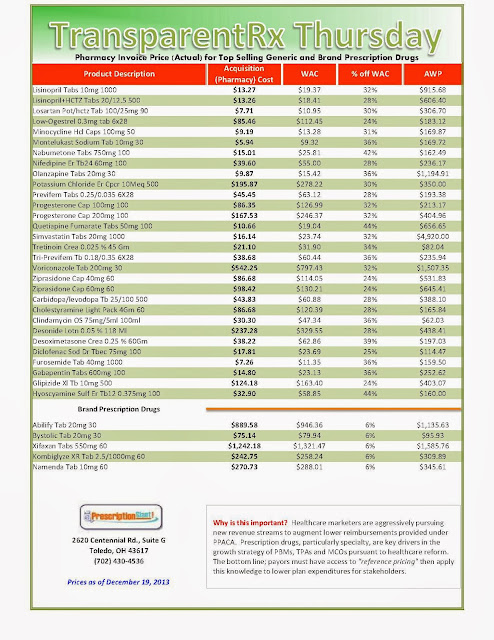

Resource for Payers: Acquisition Cost (pharmacy invoice) for Popular Brand & Generic Prescription Drugs

Include a semi-annual market check in your PBM contract language. Market checks provide each payer the ability, during the contract, to see if better pricing is available in the marketplace compared to what the client is currently receiving. When better pricing is discovered the contract language should stipulate the client be indemnified. Do not allow the PBM to limit the market check language to a similar size client, benefit design and/or drug utilization. In this case, the market check language is effectually meaningless. |

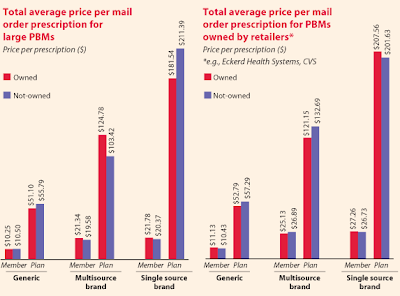

Payers: Know Your Prescription Drug Opportunity Costs

Excessive Mark-ups from Mail-order Prescriptions

It is not uncommon for some PBMs to mark-up mail-order medications as much as 500%! Why do you think traditional PBMs push so hard to move prescriptions to mail-order from retail?

A fiduciary PBM will not make an undisclosed profit from mail-order dispensed medications. Again, it will only charge its plan sponsor a flat administrative fee per claim unless some other arrangement has been agreed upon. The savings are passed back to plan sponsor reducing actual plan costs.

This is not to say that drugs dispensed via mail-order are a bad thing. In fact, mail-order can offer quite a bit of savings. But you must be aware of the arbitrage opportunities for non-fiduciary pharmacy benefits managers and eliminate them.

Again, if you don’t know the spread even exists or its amount how can a CFO or benefits director possibly determine the actual cost of the plan? This begs the question, “how does this happen?”

A simple example is when a PBM has different MAC price lists for plan sponsors and pharmacies. These MAC lists may differ in the number of drugs listed and/or their respective prices. A fiduciary PBM will not have any spreads and should contractually bound itself to such.

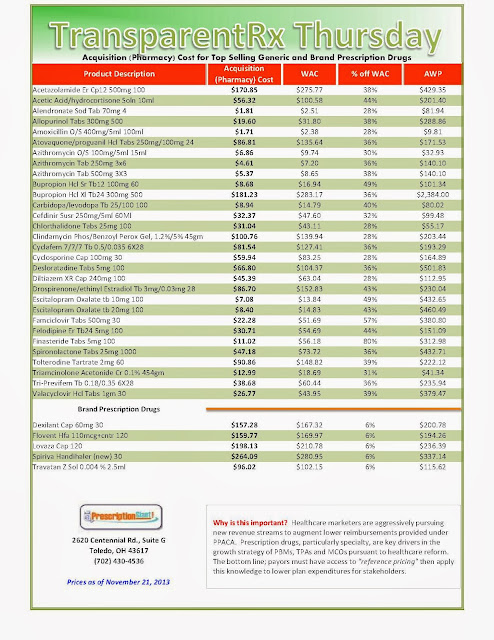

“Actual” Acquisition Costs (what pharmacy pays) of Top Selling Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs: for Payers

_1.jpg) | ||

As of 12/5/2013 – Published Weekly on Thursdays

Step #1: Obtain a price list for generic prescription drugs from your broker, TPA, ASO or PBM every month. Step #2: In addition, request an electronic copy of all your prescription transactions (claims) for the billing cycle which coincides with the date of your price list. Step #3: Compare approximately 10 to 20 prescription claims against the price list to confirm contract agreement. It’s impractical to verify all claims, but 10 is a sample size large enough to extract some good assumptions. Step #4: Now take it one step further. Check what your organization has paid, for prescription drugs, against our pharmacy cost then determine if a problem exists. When there is a 10% or more price differential (paid versus actual cost) we consider this a problem. Multiple price differential discoveries means that your organization or client is likely overpaying. REPEAT these steps once per month.

|

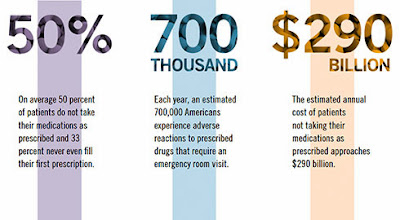

Some Patients Need Help with Medication Adherence from Pharmacists

Former Surgeon General C. Everett Koop once remarked, “Drugs don’t work in patients who don’t take them.”

These findings show that there are opportunities for prescription drug plans and policymakers to increase the nation’s overall adherence grade. On a federal level, NCPA urges Congress to pass the Medication Therapy Management Empowerment Act (S. 557 in the U.S. Senate and H.R. 1024 in the U.S. House of Representatives) to expand medication therapy management (MTM) services to Medicare Part D beneficiaries. This would not cost the government a dime; previous MTM programs have been shown to lower overall costs as increased pharmacist engagement with patients has avoided costlier health care treatments and procedures.

There is a vested interest for all to increase adherence rates in patients, and enacting the aforementioned changes will help to reach that goal. By implementing common-sense reforms, we can help improve the adherence grade. After all, when it comes to safe medication use, anything less than an “A” is unacceptable.

Hoey is CEO of the National Community Pharmacists Association. The research referred to was commissioned by NCPA as part of the association’s Pharmacists Advancing Medication Adherence (PAMA) initiative, which is sponsored by Pfizer, Merck, and Cardinal Health Foundation.

Prescription Drug Prices: 10 Definitions All Payers $hould Know

Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) is the average price paid to the manufacturer for the drug in the United States by wholesalers for drugs distributed to retail community pharmacies and by retail community pharmacies that purchase drugs directly from the manufacturer. The health reform law excludes payments and rebates or discounts provided to certain providers and payers from the calculation of AMP.

In March of this year, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) again amended the legal definition of average manufacturer price (AMP). AMP uniquely serves to determine both a multiple source drug’s reimbursement amount and the rebate amounts for single source, innovator single source, and multiple source drugs within the Medicaid program. No other pricing metric serves this dual function.

Average Sales Price (ASP) – In 2005, Medicare began to pay for most drugs using an entirely new methodology based on ASP rather than AWP. Unlike AWP and WAC, there is a specific method to calculate ASP set forth in the MMA and the Act. Section 1847A(c) of the Act, as amended by the MMA, defines ASP as a manufacturer’s unit sales of a drug to all purchasers in the United States in a calendar quarter divided by the total number of drug units sold by the manufacturer in that same quarter.

The ASP is net of any price concessions such as volume, prompt pay, and cash discounts; free goods contingent on purchase requirements; chargebacks; and rebates other than those obtained through the Medicaid drug rebate program. Certain sales are exempt from the calculation of ASP, including sales at a nominal charge.

Average Wholesale Price (AWP) is not based on actual transactional, marketplace price data. Despite its name and its sometime use as a price index, the published AWP is not an average of actual wholesale prices. It is not intended to represent, and cannot be assumed to reflect, actual transaction prices.

A wholesaler or other direct purchaser from a pharmaceutical manufacturer may agree to sell its products to one or more of its customers at prices that on their face are effectively lower than the published AWP.

AWP information does not reflect any such lower pricing that may be made available in actual purchase transactions through a variety of methods, including, but not limited to, purchase, prompt-pay or other discounts, volume or other rebates or credits, or a variety of other price reduction arrangements.

Direct Price (DP) is the price directly reported to AWP publishers by a manufacturer as the list price at which non-wholesalers and healthcare providers may purchase drug products from that manufacturer. These publishers generally do not receive a reported DP for drugs that are sold by a manufacturer exclusively through wholesalers, although in some cases both a DP and a WAC may be provided at the manufacturer’s discretion.

DP does not represent an actual sales price in any single transaction or group of transactions between a manufacturer and a non-wholesaler or healthcare provider, as any manufacturer may agree to sell its products to one or more customers at a lower price through any number of methods, including, but not limited to, discounts, rebates, credits or other net price reduction arrangements.

Federal Supply Schedule (FSS) are prices paid to manufacturers by the VA, other federal agencies, and certain other entities, such as Indian tribal governments, are set by the Federal Supply Schedule (FSS). Under the Veterans Health Care Act of 1992, manufacturers must make drugs available to covered entities at the FSS price as a condition of eligibility for Medicaid reimbursement.

FSS prices are negotiated with manufacturers by the VA.15 In general, the FSS price may be no higher than the lowest contractual price charged by the manufacturer to any non-federal purchaser under similar terms and conditions. In order to determine this price, manufacturers supply the VA with information on price discounts and rebates offered to different customers and the terms and conditions involved.

Under certain conditions, the VA may accept an FSS price that is higher than the price offered to some non-federal customers. According to the GAO, average FSS prices are more than 50 percent below the non-federal average manufacturer’s price.

Ingredient Cost

- BRAND INGREDIENT COSTS – the discount from the list price, also called the Average Wholesale Price or AWP. Typical discounts range from AWP-12% to AWP-15%. A PBM may contract with a retail pharmacy at AWP-15% and then offer you an average discount of AWP-12%, keeping the difference. This is called a “spread” or “differential pricing.” Each percentage point of withhold is worth approximately $0.60 per script.

- GENERIC INGREDIENT COSTS – generic discounts are priced in one of two ways: (1) as an AWP discount or (2) at a Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC). There is usually a large gap between these pricing elements – about $6.40 per prescription. Ask your PBM to price out the top 50 generics used in the previous year, giving you both the list price and the discounted pricing (either MAC or AWP MAC) and disclose whether your MAC pricing is cost effective. Interestingly, PBM’s derive revenue from MAC programs by contracting with pharmacies at MAC pricing and charging you the AWP discount. This is another form of differential pricing.

Some of the factors that PBMs consider to choose products for inclusion on a list are availability of the product in the marketplace, whether the product is obtainable from more than one manufacturer, how the product is rated by the FDA in relation to the innovator drug and price differences between the brand and generic products. However, there is no standardization in the industry as to the criteria for the inclusion of drugs on MAC lists or for the methodology as to how the maximum price is determined, changed or updated.

Suggested Wholesale Price (SWP) is the price that a manufacturer suggests wholesalers charge when selling the manufacturer’s drug to the wholesaler’s customers, as reported by the manufacturer. The SWP does not necessarily represent the actual sales price used by a wholesaler in any specific transaction or group of transactions with its own customers. Wholesalers determine the actual prices at which they sell drug products to their respective customers, based on a variety of competitive, customer and market factors.

Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) is the price directly reported to publishers, like Wolters Kluwer Health, by a manufacturer as the list price at which wholesalers may purchase drug products from that manufacturer. WAC does not represent an actual sales price in any single transaction or group of transactions between a manufacturer and a wholesaler, as any manufacturer may agree to sell its products to one or more customers at a lower price through any number of methods, including, but not limited to, discounts, rebates, credits or other net price reduction arrangements.

Click here to register for: “How To Slash the Cost of Your PBM Service, up to 50%, Without Changing Providers or Employee Benefit Levels.”

“Actual” Acquisition Costs (what pharmacy pays) of Top Selling Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs: for Payers

_1.jpg) |

| As of 11/21/2013 – Published Weekly on Thursdays |

| How to Determine if Your Company [or Client] is Overpaying |

Step #2: In addition, request an electronic copy of all your prescription transactions (claims) for the billing cycle which coincides with the date of your price list.

Step #3: Compare approximately 10 to 20 prescription claims against the price list to confirm contract agreement. It’s impractical to verify all claims, but 10 is a sample size large enough to extract some good assumptions.

Step #4: Now take it one step further. Check what your organization has paid, for prescription drugs, against our pharmacy cost then determine if a problem exists. When there is a 10% or more price differential (paid versus actual cost) we consider this a problem.

Multiple price differential discoveries means that your organization or client is likely overpaying. REPEAT these steps once per month.

Include a semi-annual market check in your PBM contract language. Market checks provide each payer the ability, during the contract, to see if better pricing is available in the marketplace compared to what the client is currently receiving. When better pricing is discovered the contract language should stipulate the client be indemnified. Do not allow the PBM to limit the market check language to a similar size client, benefit design and/or drug utilization. In this case, the market check language is effectually meaningless. |

Pharmacy Benefits: Eight Ways it May Unfold in 2014

I. Generic Drug Price Increase

While most of the country is ecstatic about the “Patent Cliff” not many payers have considered the potential negative effect on relative prices for generic prescription drugs. It only makes sense, as competition decreases and demand increases, prices will eventually follow suit.

Furthermore, traditional PBMs will lose valuable manufacturer revenue or rebates. Some PBMs will undoubtedly look to make up the difference thus generic drug prices, your MAC prices, will be the first stop.

In the online marketing world the key to success, in my opinion, is a relentless focus on A/B split testing. The same is true for payers; where those whom relentlessly monitor drug costs throughout the year, making changes on the fly, minimize expenditures.

Those payers whom more or less sign the contract, cut the check and wait for the renewal period unknowingly pay for the private corporate jets! Find a reliable source for reference pricing and relentlessly monitor costs.

Specialty drugs are the fastest growing segment in the pharmaceutical supply chain. The most common cost-share tier among our plan sponsors is three-tier — generics, preferred brands, non- preferred brands. We are starting to see the emergence of innovative cost-share structures with five or more tiers, but it is unclear whether these will become standard practice.

The co-pay differential between tiers, in our pharmacy, continues to widen. The difference between tier one and tier two co-pays has increased to $21 (compared to $5 about seven years ago).

Fifty-five percent of employers that now provide pharmacy benefits for Medicare-eligible retirees said they plan to continue offering the benefit, down from 75 percent in the New York-based consulting firm’s 2011 survey.

|

| Courtesy of Forbes.com |

“Employers have options for controlling prescription drug costs for Medicare-eligible participants,” Paul Burns, an Atlanta-based principal at Buck Consultants, said in a statement.

“For example, since retiree drug subsidy payments are no longer tax-exempt and do not keep pace with rising drug costs, some employers are considering moving to an employer group waiver plan to take advantage of additional subsidies available as a result of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,” he said.

MTM is a distinct service or group of services which optimize therapeutic outcomes for individual patients. As of 2013, MTM is approved for provision to Medicare Part D enrollees who have multiple chronic conditions (with a maximum of three plan selected chronic conditions being the lower limit), are taking multiple Part D drugs, and are likely to incur annual drug costs that exceed $3,144. All Medicare beneficiaries who meet the above criteria as defined by each plan are automatically eligible to receive MTM services unless they voluntarily opt-out.

On the other hand, the provision of MTM services to non-Medicare enrollees by commercial health plans is less defined. Each plan has the liberty to devise different eligibility requirements together with different MTM service component which makes cross-program comparisons in such a heterogeneous environment quite difficult.

Supporters of MTM (professional pharmacy societies, policy experts, etc.) would like to show health decision makers that tracking and evaluating MTM services outputs using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes (approved as Category I codes in 2008) that MTM services result in better health outcomes cost reductions and positive return on investment in patients that need better medication management.

V. Health Exchanges; Private and Public By Tom Norton

Even though the specifics of how PBMs under Obamacare will operate are unknown, I was told by many that if you want to understand how this new Obamacare PBM market is likely to play out, you should look to other insurance markets for insight.

In particular, they said, the PBM operations in the Medicare Part D marketplace and even more to the point, the Rx services being offered by PBMs in the new private health exchanges, will provide a sense of the PBM offerings to be provided in Obamacare.

Perhaps an even more important PBM real world example is what is going on right now in the private health exchange environment. This is because it closely resembles the insurance concept planned for Obamacare.

Over the past few months, several large companies (Walgreens, IBM, GE, and others) have announced that they are moving their employees out of “defined benefit” health insurance plans, and placing them into “defined contribution” programs. This will be accomplished by utilizing private health exchanges. What exactly are these exchanges?

Private health exchanges have several different models. Some provide “self insured” programs to provide healthcare to individuals, while most offer group health insurance to employers under “fully insured” programs. The objective of both is to reduce the cost of healthcare to the employer.

This approach differs from today’s “defined benefit” insurance plans in which the PBMs are frequently “carved out” of the general health benefit and stand alone as separate services. PBMs do save the insurer money in this environment, but it’s thought they could save more if they were “carved in” to the insurance offering.

I have noticed a trend in the PBM industry where self-insured organizations like employers and unions are making the transition to all-cash programs. Although I’m unsure to all the reasons for the change, one thing is clear and that is at least part of the change is due to the uncertainty provided by PPACA. Payers want to have control and relinquishing it is a scary proposition.

Providing the broadest access to members may no longer trump the more favorable pricing of a narrowed network. A large and growing supply of retail pharmacies makes the limited network approach possible.

VIII. Specialty Drugs

Payers continue to be challenged by rapidly rising prescription drug costs, particularly specialty drugs. However, traditional [and some transparent] Pharmacy Benefit Managers offer the same elixir for controlling these costs as they did a decade ago: increase patient use of mail-order, use of preferred or narrow pharmacy networks, a formulary design which promotes preferred drugs, reduce patient co-share for better outcomes.

While the aforementioned tactics do assist in controlling costs, they’re standard practice and are not the aggressive measures necessary to help reduce or control spending. Payers should hire fiduciary PBMs – those legally obligated to truly put clients and their members first; before shareholders and profitability.

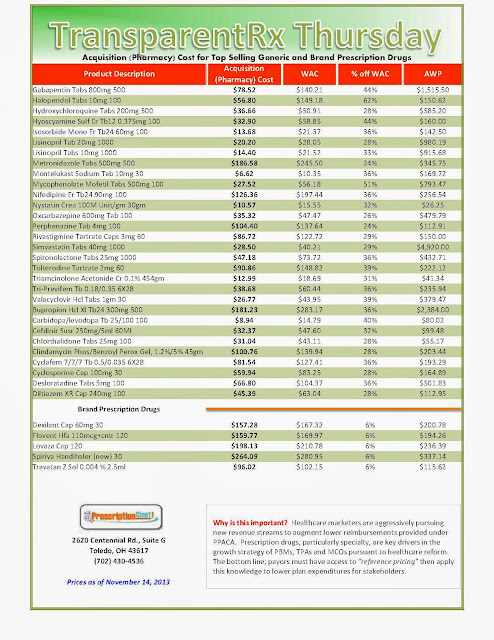

“Actual” Acquisition Costs (what pharmacy pays) of Top Selling Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs: for Payers

_1.jpg) | ||

As of 11/14/2013 – Published Weekly on Thursdays

Step #1: Obtain a price list for generic prescription drugs from your broker, TPA, ASO or PBM every month. Step #2: In addition, request an electronic copy of all your prescription transactions (claims) for the billing cycle which coincides with the date of your price list. Step #3: Compare approximately 10 to 20 prescription claims against the price list to confirm contract agreement. It’s impractical to verify all claims, but 10 is a sample size large enough to extract some good assumptions. Step #4: Now take it one step further. Check what your organization has paid, for prescription drugs, against our pharmacy cost then determine if a problem exists. When there is a 10% or more price differential (paid versus actual cost) we consider this a problem. Multiple price differential discoveries means that your organization or client is likely overpaying. REPEAT these steps once per month.

|

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)

.png)