Learned Helplessness: The Biggest Reason Non-Fiduciary PBMs Getaway with Overbilling

|

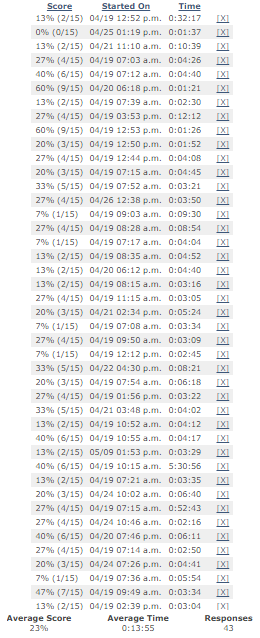

| Table 1: Scores from a Very Basic Pharmacy Benefits Quiz |

Keep in mind this is a fairly large corporation with more than 5000 employees. I asked the pharmacist was there a reason why they didn’t have a customized formulary? A representative from their third-party administrator (TPA) quickly chimed in and responded with, “we use the incumbent PBMs formulary but with edits.”

I pushed back with, “does it make sense that you allow a non-fiduciary PBM to control your formulary when it stands to benefit from how it is ultimately managed?” It is at this point when the pharmacist made a startling comment. The response to my question was, “we don’t have a customized formulary because we don’t have a P&T committee.”

Here is the problem with that statement. No third-party payer requires an in-house P&T committee in order to take advantage of a customized formulary. There are reputable companies who specialize in formulary build-out and subsequent management of the formulary who may also maintain a P&T committee. Because these companies don’t stand to benefit from any rebate dollars, their primary focus is drug efficacy, safety and cost-effectiveness not what’s in it for them.

The decision to include a drug on a drug formulary is a process that considers such factors as efficacy, safety and cost-effectiveness. In managed health care plans, formularies are generally developed and maintained by a pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) committee. The job of a P&T committee is to identify those products that are most medically appropriate and cost-effective. Overall, the P&T committee is tasked with determining what drug treatments best serve interests of a given patient population.

That being said, a customized formulary is not the best option for every self-funded employer. But for the company in question a customized formulary is ideal provided the requisite level of sophistication is there to see it through.

Because the pharmacist was unaware of the 3rd party formulary management option, learned helplessness or relying too heavily on the PBM will lead to overpayments. A la carte services (mix of insourcing and outsourcing) isn’t a new concept and is an effective way to get a good price point for PBM services.

PBMs will provide transparency and disclosure to a level demanded by the competitive market and generally rely on the demands of prospective clients for disclosure in negotiating their contracts. The best proponent of transparency is informed and sophisticated purchasers of PBM services.

Table 1 represents the scores from a very basic quiz to test pharmacy benefits aptitude. It was offered to my entire mailing list which consists of over 5,000 professionals who either buy PBM services or consult on the purchasing decision. A sample size of just 43 was required to represent the entire list of 5,000 (a 15% margin of error and 95% confidence level). The confidence level is the amount of uncertainty tolerated.

The average score was just 23%! So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that transparency is so elusive. With test scores like this one has to wonder is it the PBM’s unwillingness to be transparent or the purchaser’s inability to drive complete transparency which leads to excessive overpayments for PBM services?

Assessing transparency will be more effectively done by a trained eye with personal knowledge of the purchaser’s benefit and disclosure goals. The purchaser needs to understand not only what they want to achieve in their relationship with their PBM but also the competitive market and their ability to drive disclosure of details on services important to them.